Voices of family history: Problems of the textualisation Strategy

Pauliina Latvala

In 1997 the Folklore Archive of the Finnish Literature Society organised a nation-wide collection project called The Great Narrative of the Family. The purpose of the project was to give voice to bearers of the unofficial history. My methodological basement might be called a folkloristic-linguistic approach, because I focus on the different ways language and linguistic means elicit the writer's opinions, meanings and emotions. I utilise critical text-oriented research to outline the fact that writing for a collection project is a specific but heterogenic genre of writing, because the texts are produced in a multidimensional context. How does the writer adopt various positions and use style in these highly personal and emotional texts?

Written narrative in the context of the Folklore Archive

When responding to a collection project, the communication is almost always literary. Written language always has its specific features; where pauses and intensity express meanings in oral communication, literary texts have their own ways of emphasising the writer's ideas. Narrators create texts by using conventions shared in their culture. The texts could also be examined as representations fixed in the time which produced them and the then-current literary and narrative models. The narrator has multiple choices in narrating and interpreting emotionally sensitive topics. The writer has a continuous dialogue between himself/herself, the imagined reader and the surrounding writing culture as he/she finally makes the choice of the register. One of the writers expressed this as follows:

We long considered the way we would narrate. Conversation? Years? People? We decided to be faceless, strongly committed to the past. We wanted to describe how they survived. (SKS.SUKU 1997: 21861)

Romy Clark and Roz Ivanic (1997: 138) explain the use of conventions as follows: "Discourse conventions differ from one discourse type to another. Discourse types mean sets of discourse conventions associated with a particular purpose for writing or with a particular topic being written about: 'resources in the air on which people draw as they write.' Writing includes both the physical, mental and interpersonal literary practices that constitute and surround the act of writing and discourse conventions 'ways of using language in writing'. Both literary practices and discourse conventions have subject positions inscribed in them, and writers are positioned by both of these simultaneously."

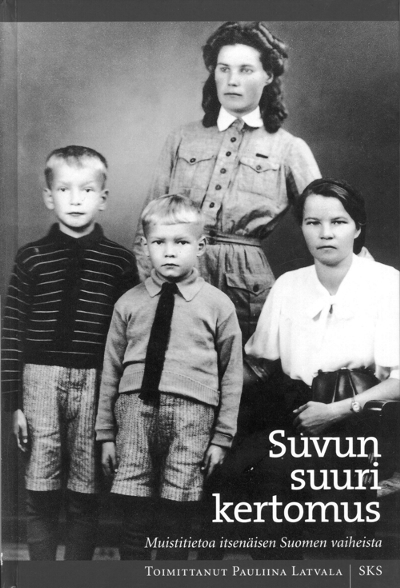

Written narratives are often supplemented by photos. Here: building a new shed in Ilomantsi, 1945. Photo: from the collection of family narratives compiled by Pauliina Latvala Suvun suuri kertomus (The Great Narrative of the Family ) Helsinki 2001, p. 181. The basis of my analysis is close to M. A. K. Halliday's model of semantic components in which the interactive, the textual and the ideational components are simultaneously present in the text. Here my special interest is concentrated on the interactive component, because it consists of the roles of both the writer and the reader. The meaning of a textual approach is to examine linguistic choices: what kinds of meaning do different expressions create in a text and are these choices conscious or not (Halliday 1978: 117)?

Writing has been understood in linguistic-orientated research as both an autonomous (Ong 1982; Goody 1968) and context-bound act (Street 1984: 6-10; Clark & Ivanic 1997: 59). When dealing with texts produced for an archive, it is essential to analyse their multidimensional context. First, the production of the text is not context-free: it has been written in Finland. Finns are active amateur writers and there are writing circles in every town. Archives and museums have organised collection projects for decades. In addition, the texts reflect the writers' sense of history (see Ahonen 1998: 25-26). Both the media and oral history in each period have greatly influenced people's images of our recent history. The reinterpretation of history has been marked in the 1990s; for example women's experiences during wartime as well as childhood memories about being an evacuee have been discussed in the media. In 1997, the need for narrating of the wartime was evident.

Secondly, the institutional context is remarkable: the Finnish Folklore Society is a historical and famous organiser, and the collection was dedicated to the jubilee of the independence of Finland. In the leaflet the sponsors were mentioned: The Finnish Association for Local Culture and Heritage and The Association for Kalevala Women. The jury was also prestigious: the Minister of Education was the chairman, and the heads of the Folklore Archive and a professor were members. These institutions and positions create ideas and stereotypes of the receiver and reader of the texts. The following example expresses the position of the writer:

What kind of interesting stories could I tell you about my family's past? Me, an ordinary man, who has lived in the city, not in the traditional agrarian environment, not in the area of original folklore or music. My parents left the countryside and moved to town. Could there be anything to tell? Is there anything inherited, anything that has lasted through six generations? (SKS.SUKU 1997: 26757-29708)

Many narrators belonged to a circle of regular archive writers and thus were already familiar with the discourse. They already had some idea of the limits and purpose of this kind of writing. Each narrator forms a framework for the collection, and images of the reader. This image is strengthened by the instruction brochure, which stimulates the narrator and represents the receiver to some degree. The dialogue between the receiver and the writer is based on the brochure (see Pöysä 1997: 39). The writers also express the correlation of influence between the archive and themselves. The Folklore Archive is often perceived as an authoritarian receiver, which is above ordinary people.

To the jury. You may throw away this answer if you are terrified the writings of an 89-year-old woman. I could not judge what was important. I guess this is nonsense. (SKS.SUKU 1997: 8606-8630)

Literary strategies

The narrators have some idea what is expected from them. Imagined expectations and the image of the reader influences the process of developing the role of the narrator. The roles differ according to the feeling of the importance of 'the visible narrator and reader'. The narrator moves from one position to another because of his/her image and the need for 'internal dialogue' (Widdowson 1983: 44) or 'reciprocity' (Nystrand 1986: 48). Vincent Crapanzano's (1992) concept of a 'shadow dialogue' illustrates the central idea of the production process of collection project texts. Here, the shadow dialogue consists of the narrators' personal experiences and emotions related to their cultural and social setting and background. This is 'the third' party of a dialogue (see Crapanzano 1992). Bakhtins' (1986: 126) concept 'a higher superaddressee' means the same: "Each dialogue takes place as if against the background of the responsive understanding of an invisibly present third party who stands above all the participants in the dialogue."

How do these shadow dialogues appear in communication? As Crapanzano (1992: 213-215) has put it: "We become aware of them when our interlocutor uses, for example, a stylistic register that appears inappropriate. He may be distracted; he may appear to be addressing someone else; he 'swerves'; he speaks automatically; he 'edits' what he has to say according to the standards that have nothing to do with the occasion as we understand it and assume he does too." The shadow dialogue is conspicuous in written texts.

People have written their memories, oral history, experiences and opinions in various genres and styles. This production process may be called a 'textualisation strategy' (Pöysä 1997: 52; vanDijk & Kintsch 1983: 205; Harvilahti 1992: 98-99). Different registers and their markers are used in text in order to express the meanings. (For the concept 'register' see Halliday 1987: 185; Foley 1995: 49-50; Wardhaugh 1986: 48, for the concept 'marker' see also Mills 1991: 21-22, 267.)

In my research material the literary discourses (see vanDijk 1985: 1) are reminiscences, life histories, (auto)biographies, fiction, and poems. The same text includes many different discourses, but one, for example life history, is usually the formation for the story. Autobiographical texts often speak about various episodes of changes in life; but they stress the childhood and even the life of the parents. Writing a fictional narrative for the Folklore Archive, one purpose may be to describe the wartime era in general and focus on the life of the working class. Poetry is a genre for emotions; there are topics like leaving the homestead or arriving in a new home as a wedded wife and a daughter-in-law. Of course, by sending their texts to the archive, some of the writers may hope to find a publisher. Disappointments, happiness and sorrow, fear, loneliness and pride are sometimes treated through humour and irony.

After dividing the texts into literary discourses, it is reasonable to ask what the purpose the selection of particular textual styles serves, for example writing a poem in the middle of prose text. Is it a conscious choice or a cultural model to channel feelings and experiences? According to one informant, poetry is the only 'free' genre that could be used to describe her deepest feelings. In another interview the narrator said that she used dialect to strengthen her personal voice. Do the writers think that the structure of a life story or memoir is very stable or do they consider it flexible? Do they think what the 'right' kind of life story or life history is? What should be included, what forgotten? How should it be started? What sort of episodes should there be? How should it end? How linear should the narration be? Some people do not name the genre, some do. To keep the readers' interest, the narrators also break rules and expectations.

In interview, one informant said that while writing, she does not try to describe others' feelings or thoughts, but while telling stories, she does. A text may also be written in a few hours without any pause, or it may be a longer process, in which a new memory always leads to a free narration. By producing different textual styles, the writing narrator can bring history closer or keep a distance from historical events. This is important, because family history is also personal history. Anna-Leena Siikala (1984: 160-188) has created a typology of oral narrators. The narrator has different scales to move along, which is in many respects similar to literary text. The chosen textual strategy determines the narrator's role, visible or not (see Pöysä 1997: 52).

By examining textual strategies we can hear not only the narrator's voice, but also the present and absent voices of the characters and the imagined reader. In William Hanks' (1989: 102) words: "Voicing in text concerns the distinctions among monologue, dialogue, direct, indirect, quoted discourse, dialogism..." Those are stylistic decisions within the text, which help the narrator provide tension and strengthen or weaken the voices. The so-called 'dramatic present', which means that the past events are told in the present tense, is also a stylistic means in life-historical texts (the concept of 'the dramatic present' see Laitinen 1998: 81). For example, when narrating an evacuee's story in the present, the history is more immediate, and the reader can easily identify with the narrator. This kind of stylistic decision may start the discourse of longing.

The so-called reader-response research has been examining the meaning and role of the reader in the writing process. Is the writer somehow related to the reader and is it apparent in the text? The concept 'reader' encompasses not only the real reader but also the implicit reader (Iser 1978: 27-29, 34). A text always has a referent. The narrator/writer imagines the readers' values, expectations, ideology. The writer's opinions about sharing or not sharing values with the imagined reader can be heard in the text (see Clark & Ivanic 1997: 144, 163-164).

Suvun suuri kertomus - selection of texts (2001) from the collection of Finnish family narratives. Most of the texts I have examined have not addressed the text to any particular person, but there are still clues as to who the addressee might be; the reader may be imagined as a young person who might not know the dialect or the old working methods, etc. There are questions addressed to a reader, the narrator may reveal his/her secrets to a reader, the reader may be amused, enlightened or his/her feelings may be appealed to. Only a small number of the texts were addressed to a researcher or to the staff of the archive. It is natural that the implicit reader of written family histories is often the narrator's relative. Some of the written family histories are even composed of the diaries or reminiscences of a late mother or grandmother and thus they are interesting to a larger group of relatives. Often this sort of family history also relates to local history and strengthens the feeling of belonging to the home place. In this respect, the imagined reader may limit the scope of writing. The narrator considers what sorts of topics are controversial; who might get angry with a particular issue. The writers also have to know the secrets of the family and consider how much of personal life they are willing to share with the readers. The texts that are addressed to the archive are often quite straightforward. The writers have often mentioned that the text cannot be published without permission. Writing is also therapeutic; the imagined reader may be the narrator him/herself in the future.

The changing positions of the narrators

The narrator's image of the reader and receiver determine the writing process and the choice of literary discourses. As Bakhtin (1986: 95) puts it: "Both the composition and the style of the utterance depend on those to whom this utterance is addressed, how the writer senses and imagines his addressees, and the force of their effect on the utterance..."

In my material a narrator acts as: recollector, meditator, reporter, and storyteller. The imagined reader has his/her own place in each role. The personal level of the texts depends on the distance from the narrated time. While narrating from the position of a recollector, the text often recalls oral conversation. The structures characteristic to oral or written communication are then mixed and the narrator lets the text sprawl. For example, sentences are not perfect, often too long and dialogues are used a lot. The typical speech-like-discourse markers include so when..., once when...., I replied that... Speech-like discourse is common in written reminiscences. Amy Shuman (1986: 12-13) states that the structure of a written story is more homogenous than the flow of conversation. Barbro Klein (1999: 11), studying quite similar archival material, has noted that some narrators use speech-like discourse a great deal. As she pointed out, the reader may hear the narrator speak to the reader. Tarja Raninen-Siiskonen (1999: 117) states that subsidiary episodes are typical of oral reminiscences. Speech-like discourse is used especially when visualising memories; for example the home:

Now, when I try to remember the village of Savotta, I can recall all the houses. And then they moved the house of my grandfather away from the village. There, a few kilometres from here, where some Estonians were living. They opened a school there in my grandfather's house. Once I told my sister that they should have left that house there, so we could at least try to remember what kind of house grandfather had. Well, my sister is three years older than I am, so she told me she could still recall some of it. I can recall the house of my grandfather's nephew, it was next to that house, green, two floors, as far as I recall, so, there was a shop and a telephone exchange... (SKS.SUKU 1997: 23254)

A meditator discusses the causes and consequences of the life of previous generations. They also try to place their stories in historical periods and reconsider their parents' life. Many narrators mention that they feel themselves and their generation to be part of a chain when writing their family history. The place of the imagined reader is outside the text of a recollector and the text of a meditator. The narrator's primary dialogue is not with the receiver but with the invisible other, 'the third' as Crapanzano (1992: 213) puts it. The narrator 'speaks' with his/her own past, and sometimes the third may be personified, becoming the narrator himself/herself when young or his/her father.

A narrator whose position can be regarded as a reporter does not reminisce. The atmosphere of the text is quite official and the narrator answers the questions asked in the leaflet. The receiver is more obviously present than in the texts of a recollector or a mediator. Emotions are not apparent and the narrator does not, for example, change the register from report to poetry. A storyteller is not afraid of relating personal feelings or adopting a personal view. History is made immediate by relating the life of named people. The narratives frame the historical events, as in the following example:

In the 1860s the famine years were very difficult. Jaakko the smith and his wife died of typhoid. The sons, Jacob and Matti put their few belongings on a wagon and shut the door of their house. So they left and joined a moving crowd of other hungry people. (SKS. SUKU1997)

There are some other positions, which differ from those mentioned above. There are texts produced from the point of view of a critical educator, for example. The texts consist of forgotten history and were written by a Finnish-Russian narrator, who wanted to correct the past and ensure that younger generation would learn what difficult times their parents had experienced and how the historians have sometimes written unjust histories.

References:

Finnish Literature Society Folklore Archive (Helsinki):

- SUKU - Suvun suuri kertomus (The Great Narrative of the Family). Manuscript collection 1997 (SKS.SUKU 1997).

Ahonen, Sirkka 1999. Historiaton sukupolvi? Historian vastaanotto ja historiallisen identiteetin rakentuminen 1990-luvun nuorison keskuudessa. Suomen historiallinen Seura. Helsinki.

Clark, Romy & Ivanic, Roz 1997. The politics of writing. London & New York, Routledge.

Crapanzano, Vincent 1992. Hermes' Dilemma and Hamlet's Desire. On the epistemology of Interpretation. Cambridge, Massachusetts & London, Harvard University Press.

VanDijk, Teun & Kintsch, Walter 1983. Strategies of Discourse comprehension. New York Academic Press.

VanDijk, Teun (ed.) 1985. Discourse and Literature. Amsterdam & Philadelphia, John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Foley, John 1995. The Singer in Tales in Performance. Bloomington & Indianapolis, Indiana University Press.

Goody, Jack (ed.) 1968. Literacy in Traditional Societies. Cambridge University Press.

Halliday, M. A. K. 1978. Language as social semiotic: the social interpretation of language and meaning. London.

Hanks, William 1989. Text and textuality. - Annual Review of Anthropology, Vol. 18.

Harvilahti, Lauri 1992. Kertovan runon keinot. Inkeriläisen runoepiikan tuottamisesta. Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seuran toimituksia 522. Helsinki.

Iser, Wolfwang 1978. The Act of Reading. Original: Der Akt des Lesens. Theorie äestetischer Wirkung. Munich, Wilhelm Fink. London, Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Klein, Barbro 1999. Folklore Archives, Heritage Politics and Ethical Dilemmas: Unpublished paper for Folklore Fellows' Summer School.

Laitinen, Lea 1998. Dramaattinen preesens poeettisena tekona. - Laitinen, Lea & Rojola, Lea (toim.). Sanan voima. Keskusteluja performatiivisuudesta. Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura. Helsinki.

Mills, Margaret 1991. Rhetorics and politics in Afghan Traditional Storytelling. University of Pennsylvania Press.

Nystrand, Martin 1986. The Structure of Written Communication: Studies in Reciprocity between Writers and Readers. Orlando Florida, Academic Press.

Ong, Walter 1982. Orality and literacy: the Technologizing of the Word. London, Methuen & Routledge.

Pöysä, Jyrki 1997. Jätkän synty. Tutkimus sosiaalisen kategorian muotoutumisesta suomalaisessa kulttuurissa ja itäsuomalaisessa metsätyöperinteessä. Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seuran Toimituksia 669. Helsinki.

Raninen-Siiskonen, Tarja 1999. Vieraana omalla maalla. Tutkimus karjalaisen siirtoväen muistelukerronnasta. Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seuran Toimituksia 766. Helsinki.

Siikala, Anna-Leena 1984. Tarina ja tulkinta. Tutkimus kansankertojista. Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seuran Toimituksia 404. Helsinki.

Shuman, Amy 1986. Storytelling rights. The use of oral and written texts by urban adolescents. Cambridge Studies in Oral and Literate Culture. Cambridge University Press.

Street, Brian 1984. Literacy in Theory and Practice. Cambridge Studies in Oral and Literate Culture 9. Cambridge University Press.

Wardhaugh, Ronald 1986. An Introduction to Sociolinguistics. Basil Blackwell.

Widdowson, H. 1983. New starts and different kinds of failure. - Freeman, Aiva & Pringle, Ian & Yalden, Janice (eds.). Learning to Write. First language/Second language. London, Longman.