On cemetery culture, with examples from Estonia and Finland

Triin Viitamees

People's attitude to death has always been slightly reluctant. And it is not really possible to completely understand the mystery of the disruption of life. Yet not everywhere is death handled alike. Even the environment in which death is placed (country - city, hospital - home) may vary considerably, and therefore the attitude to the deceased is different, to say nothing of the traditional last journey and its arrangement.

This article will shed a glance at the cemetery culture of two related nations and neighbouring countries - Estonia and Finland, primarily on the basis of grave markers. Although the many-sided source material for this article is not voluminous: 185 grave markers from Estonia, 135 from Finland; from the period of 1970s-1990s in Estonia, and mainly 1950s in Finland; a rural graveyard chosen from Estonia (Kärdla cemetery in Hiiumaa island) and a city cemetery from Finland (Malmi cemetery in Helsinki) - it is sufficient to draw certain general parallels or point out differences between the graveyard cultures of the two countries.

It must be noted about Kärdla that in addition to being a cemetery of a small town, in the 1970s-1980s Kärdla belonged to the so-called restricted zone. Therefore everything that existed was compacted and the cemetery remained an inseparable part of everyday life.

We need not observe cemetery culture in the graveyards only, it may as well be done outside the limits of it. The other world is often associated with the cemetery, it is regarded as sacred land, a boundary between the two worlds (Valk 1998: 507-508), yet when we lose a close person, we will not first go to the graveyard, but to a funeral agency and then to the stonecutter's. Comparing the stonecutters' shops of the two countries, we do not notice them in Estonia. Although the advertisements of stonecutters in Estonia exist, the workshops are located mainly on the outskirts of settlements (cities, small towns). One reason for that is the peripheral location of graveyards: if possible, the stonecutter will set up his business close to the graveyard. Another cause emerges from modern people's mental world, where death does not fit in any more. Therefore they are discarded, put out of sight. (Aho 1996: 119.) Finnish stonecutters' shops, on the contrary, are located at major roads. In Estonian society public advertising of companies that deal with death is quite modest. Public handling of death and regarding it as business is not customary here. In Finland death can be called a product, an object of sales. Items and services related to death and funerals are advertised just like overcoats, for instance, on Seppälä window displays, and therefore it is impossible for a passer-by not to notice what kind of a store that is.

If we take a look at Kärdla, a rural place, representative of a small area, we have to admit that advertising is not necessary there. There is no point in emphasising what is known anyway. Information is spread, but in such a small community it has different bases, incl those characteristic to oral tradition.

The first difference between Finland and Estonia arises from the different forms of the administrative ownership of the cemeteries. Contrary to Estonia, where most cemeteries belong to administrative units (some belong to the church), in Finland nearly all cemeteries are managed by congregations and churches. In Finland there is only one cemetery (in Kauniainen) that belongs to the local authority, which is the general practice in Estonia, but even that one belongs to the Lutheran church (HS I 2000: B12).

The general appearance of cemeteries

The Finnish researchers of cemeteries have said that their cemeteries leave an impression of being somehow too clean and sterile (Häiväoja & Nickels 1990: 49). Most graves are covered with grass (HSH 1999: 15), always neat and precisely laid out, while in Estonia gravesites are usually covered with sand or gravel. Estonian cemeteries are designed more freely.

Estonian cemeteries have been regarded as park-type graveyards. In comparison with the Finnish ones, it might be pointed out that Estonian cemeteries are sooner forest-type. Park-type cemeteries are more typical to Finland (see photos1 and 2). In a way the cemeteries in both countries look like parks, even a stranger could go for a walk there.

Photo 1 Photo 2 Estonian cemeteries can be called forest-type cemeteries; those in Finland are remarkable for their neat and orderly appearance. Photo: author's private collection.

The general look and condition of cemeteries is controlled by completely different people: in Kärdla a close relative of the deceased rakes the grave, takes flowers there and waters them. In Helsinki it all is done by hired people: for a certain sum of money grass is mowed on a regular basis and flowers are planted twice a year. The same is true for funerals: different services take care of everything up to the disposal of the body. Today the relatives of the deceased do not have to do anything else than call the funeral agency who will arrange all the rest: send the certificate of death to proper places, find a coffin, wash the dead person, clothe and place him/her into the coffin, provide transportation, book the chapel and a clergyman, and if the relatives wish, also a singer or a speaker, plan the arrangement of the whole funeral, inform the office of the cemetery of digging the grave, order flowers for the coffin and the chapel, hire coffin-carriers if they do not have their own, organise the funeral feast with catering as desired, send obituaries to newspapers, take charge of the gravestone and stonecutting and finally send an invoice for all that (Aho 1996: 119).

Such arrangements are not familiar to a rural community. For example, even today on Kärdla cemetery the relatives of the deceased themselves have to find gravediggers.

On graves in Finland there are no benches - that is why people can have a silent moment of commemoration either standing on the grave or sitting on benches at larger paths. The latter may be quite far from the grave they have come to visit.

Immediately after the funeral people come to the cemetery more frequently. According to the current way of thinking a deceased, close person is not on the graveyard where he/she was buried, but he/she is carried along in one's thoughts. The deceased one's body is not as important as the memories of him/her are (Heng 1999: A2). Great part of Europe thinks the same way. The Dutch would also rather mourn in their heart than at the grave. Today a cemetery in Dutch tradition is like a park where dogs are often walked (Kiviharju-Wiebenga 1997: D3).

The place of eternal rest and ways of marking it

The general outward appearance of cemeteries was significantly affected by cremation. In Helsinki cremation was introduced in 1926 when the first crematorium in Finland was established in Hietaniemi. Until World War II cremations were still rare. Only after the war the new type of funeral became common, due to ideological changes and the scarcity of land suitable for burial grounds. By the beginning of the 1980s there were as many cremations as human burials on the cemeteries of Helsinki, by the year 1996 the proportion of cremations had increased to three of four, or 75% (HSH 1999: 8, 16).

There are three crematoriums in Estonia: in Tallinnas (established in 1993), in Tartu (1997) and Jõhvi (2000). At present the target group of cremation consists of people living in larger communities, a villager still prefers the traditional burial in a coffin.

It must be still kept in mind that the material I have studied dates to the Finland of the 1950s, when cremation only started to spread. Nevertheless, the selected part of the cemetery is intended for burials in urns. Therefore, as to the type of burying, the chosen part of the cemetery, where burials were started fifty years ago already, does not differ in general appearance from a typical modern part of a cemetery in Helsinki.

Cremation has no effect on the image of Kärdla cemetery in the island of Hiiumaa. It is more like a graveyard of a rural community, where, even if the dead person is buried in an urn, it does not reflect in the general aspect. The same can be said about the rural districts of Finland, where still coffin burials are preferred. The main reason for cremation is the scarcity of land and consequently, the higher price of land. As a result of urbanisation the existing cemeteries have run out of space. The price of a burial plot has risen and therefore its dimensions have been reduced to a minimum, which in its turn favours burying in an urn. The burial plots for urns on the cemeteries of Helsinki are one metre in width; the same width is used for similar plots in Tartu.

Although dimensions are smaller, it does not mean that the number of potential burials will decrease. In Finland a gravemark carries the personal data of many different people, so a Finnish gravemark may be regarded as a family gravestone. A gravemark is usually bought immediately after the burial plot is purchased and the problem how to place the data of more people on one stone will have to be solved later.

The layout of data is not arbitrary. For example on the Helsinki cemetery there was a gravestone, on which at the time of collecting this material there were only two names: one cut at the bottom, and the other at the top of the stone, the first probably the name of the great-grandmother and the other that of her great-grandchild (see figure 1). This allows the conclusion to be drawn that generally the names of spouses are placed close to one another and the data of children next to their parents' rather than grandparents' names. Most frequently the data are designed in chronological order. The above-mentioned family tree model is followed in exceptional cases, when for instance the personal data of an untimely dead child or youngster have to be placed on the gravemark.

Figure 1. Data given on the gravestone follows the scheme of a family tree.

The same gravestone also refers to urbanisation and migration. Migration in its turn may and evidently in this case has led to the situation where one of the spouses is buried on the village graveyard in the former home, the other has found the last resting place on a city cemetery, which the relatives who have moved here find easier to visit.The Finnish clearly prefer family tombstones (90%) as opposed to the grave markers typically in memory of one person in Estonia. In the newest sector of Kärdla cemetery 65% of all gravestones are dedicated to one person and 30% to spouses together. The rest are gravestones marking family burial grounds. These grave markers differ from the Finnish ones - in Estonia the common name of the family is cut in the stone, no more specific data is added. Additional data is either on personal stones next to the common family stone or will remain unknown to the passer-by. By the beginning of the 1970s it was not customary to have more than two people's personal data on one gravestone, among the observed material there was only one gravestone dedicated to a grandmother, grandfather and grandchild.

The prevailing grave marker in both countries is the gravestone. Crosses are used, but their function is mainly to mark the burial plot temporarily. Gravestones are still surprisingly different in their shape: the Estonian stone with its broken edge strives for natural look, the Finnish one, on the contrary, is a traditional rectangle, which people call, with a bit of irony matkalaukku stone (Yli-Kovero 1999b: D1). The popularity of the broken-edged stone started in Estonia at the end of the 1970s. Stonecutters justify using the natural stone because of its cheapness, as well as the fact that the square, fully faced gravestone would seem artificial.

Earlier the choice of material was wide in Estonia, now mostly granite is used. The raw material is brought from Finland and Karelia, also from the Ukraine. Of colours black is preferred (Viitamees 2001: 7). On Kärdla cemetery about 75% of all gravestones are dark-coloured. The advantage of the black surface is that the text cut in it is more legible. In the surveyed part of cemetery in Finland the dominant stone colour was black, too (55%), quite frequently red granite could be seen (33%).

The most popular size for gravestones in Finland is 60 70 cm (Yli-Kovero 1999a: D2), in Estonia the so-called matchbox size (70 50 cm) is regarded the most suitable (Viitamees 2001: 7). Notable is also the orientation of stones: in Finland they are upright, in Estonia they are placed on their longer side (see figure 2).

Figure 2. Though comparable in size, the rgavestones are placed on the grave differently: in Finland they stand upright, in Estonia - horizontally.

Finnish gravestones are different in depth than Estonian ones: the common depth is 15 cm there (Yli-Kovero 1999a: D2), our stones are usually no more than 12 cm in depth (S 2001). Moving geographically, gravestones become significantly thinner, from 10 cm in Sweden to 7.5 cm in Great Britain (Yli-Kovero 1999a: D2).

Crosses (mainly wooden) can be found on the cemeteries of both countries, crosses are used as temporary markers only. Within a year or two the wooden crosses are replaced by gravestones (Viitamees 2001: 7). In Finland the custom of initially marking the grave with a cross or a plate is not widespread. While visiting the newest and actively used parts of cemeteries, unmarked graves can be seen, but usually a proper gravestone has been obtained. Obviously in Finland gravestones are ordered in the course of funeral arrangements or immediately after the funeral.

Both in Finland and in Estonia crosses are usually painted white. Kärdla cemetery in Hiiumaa is characterised by silvery crosses (more than a half of the wooden crosses of the studied material).

The larger number of crosses in Estonia may be justified by poverty on the one hand and the greater popularity of our personal gravestones: the cross will be the first marker of the burial plot. In Finland a gravestone is procured at the time of the first death in the family. Later there is the common stone of the family on the grave already, there is no direct need for the cross and only a new name has to be tooled in the stone.

Because of the family gravestone there is only one marker on a grave in Finland. In Estonia it is not uncommon to find two or more (slightly more than 10% of family or extended family graves, according to the material of Kärdla cemetery).

If there are more than only one grave marker, the general impression of the grave will depend on the arrangement of the stones on the plot, which is usually determined by the nature of the burial and the size of the given plot. When the corpse is buried in a coffin, the plot is larger and the markers are placed side by side. In case of urn burial the area of one grave is smaller, therefore, if there are many grave markers, they are placed behind one another. The first arrangement may be more typical to rural places where cremation is not available yet, the latter to larger settlements where cremation is rapidly gaining popularity due to the expensiveness and shortage of land.

The graves of public figures

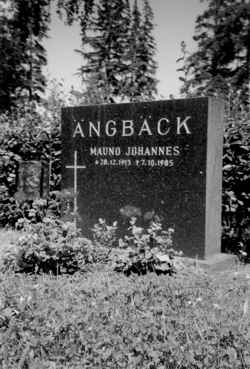

A noticeable difference in the Finnish and Estonian cemetery traditions is revealed in the way how famous people's graves are marked. In Finland the usual grave marker is a stone belonging to the whole family, so the personal data of famous people are cut on the commonest family gravestones (see photos 3 and 4). This causes a situation which may appear quite strange to Estonians. For example, the grave of the once popular Finnish film star Tauno Palo cannot be found without asking for directions. This situation is strange for us primarily because usually our gravestones even on the most modest rural graveyard can be divided into two.

Photo 3. A usual Finnish gravestone according to the research conducted on the Malmi cemetery. Photo: author's private collection.

Photo 4. The gravestones of public figures buried on Malmi graveyard are not different from others. Photo: author's private collection.

The first are the grave markers of common people, there may be some local characteristic features about them but they do not destroy the general impression. The so-called standard grave marker among the material collected from Kärdla cemetery was the dark granite gravestone, with broken edges (see photo 5). It was either a family or a personal gravestone; in either case the names were written in block capitals and were placed below each other. Only the year of birth and death were given, separated by a hyphen. The figure was on the left side of the stone and it was either a Latin cross or a weeping birch. Flowers were used to decorate the gravestones of women and children, the sea and symbols related to the sea, which is more local and typical of the island, were usually on men's gravestones.

Photo 5. An example of the most widely used gravestones in Estonia (Kärdla cemetery). Photo: author's private collection.

Opposed to the above-mentioned usual variant of the gravestone in Estonia are the grave markers of public figures, which vary from the established stereotype and do not follow the general canon of gravestones, thus remaining detached. In the newest part of Kärdla cemetery three such grave markers can be found.

In the first case already the shape of the gravestone is singular, more like a monument than a usual gravestone (see photos 6 and 7). This is the tombstone of the local artist Paul Kamm, with his autograph fixed on it.

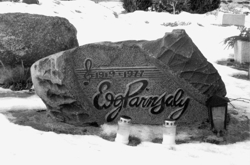

An autograph can also be found on the gravestone of the conductor Edgar Pärnsalu (see photo 8). But his gravestone is also unusual because his full name was not cut on it. Probably it is so because he was considered famous enough and further information was unnecessary.

It is quite usual that on the gravestones of public figures in addition to personal data there are some figures or an epitaph. Thus the stave and the G clef on the gravestone of Edgar Pärnsalu refer to his activities. On the gravestone of Aleksander Resta, director, we find a crying and a laughing mask and the epitaph: "You've laid a firm path in the cultural history of Hiiumaa" (see photo 9).

Photo 6 Photo 7 Photo 8 Photo 9 Photo 6-9.

The graves of public figures on Kärdla cemetery are notably different from others. Photo: author's private collection.

Of course, there are unique gravestones of public figures also in Finland, but there are fewer of them and they are rather on one specific cemetery (e.g. Hietaniemi in Helsinki) than everywhere in the country.

The inscription as an obituary to the deceased

The data given in the inscription may speak of the life of the deceased, his/her personality, activities, etc., at the same time it may indirectly also refer to the survivors. The inscription is all the information tooled in the surface of the gravestone:

- personal data, which usually consist in names and dates of birth and death, in exceptional cases names may be replaced by a symbol representing a person or a group (for example '16' from Kärdla cemetery);

- a figure, which includes visual symbols (for example the cross) and pictures (the sea with a sailing ship on it);

- an epitaph is the textual part of the inscription, proceeding from its position with respect to the name of the deceased it can be an introductory text (for instance Here rests in divine peace …) and an end text (Memory is eternal) (see further Ots 1995: 91).The inscription may be presented in many ways: it may be tooled in the surface or emphasised by using metal colour. The latter is more popular in Finland. Among the studied material 65% were gold- or silver-coloured or painted in another colour. Projecting metal is used in Finland mainly for distinguishing the family name.

In Estonia the inscription is usually not painted, that is why the text becomes illegible after some time or due to the colour of the gravestone (light dolomite, light red, light grey granite).

Although in the two neighbouring countries there are no basic differences in presenting personal data on gravestones, certain divergences still occur. For example, in Estonia more inscriptions with incomplete data can be found, mostly the dates of birth and death are presented partially or names are written irregularly. In Finland the precise and complete data of the deceased is cut in the gravestone, which means that both the first and family name are given, sometimes also the maiden name of the woman (35% of the women), in case of the dates of birth and death the year, month and the date are marked. In Estonia the presenting of the maiden name of a woman has never been widespread (Ots 1995: 91). According to the material from Kärdla cemetery no fundamental conclusions can be made about it. It may be noted that evidently the former maiden name was brought out primarily at the beginning of the 20th century. Its usage became less frequent in the first half of the century and later it has been used in very rare cases (Viitamees 2001).

Due to its relatively restricted use, the maiden name of a woman cannot be regarded as belonging to the personal data of a woman, therefore the data on Estonian grave markers may be considered complete in most cases. Exceptions are small children and stillborn babies. In the latter case there may be a symbolic name on the grave marker, for instance Missisipi. According to the registry office of Hiiu County Government, Missisipi has never been registered as a first name.

In comparison with Finland the dates of birth and death are written shorter in Estonia. Thus from the material of Kärdla cemetery half of the gravestones carry only the year of birth and death (compare: one gravestone in Helsinki), on 5% there are no data (one in Helsinki, and it was a wooden cross).

The general tradition of writing dates is reflected also on gravestones: in Finland Arabic numerals, in Estonia Roman numerals (90%) are used for denoting the month, like it was customary in our letter-writing traditions some time ago.

In Finland the use of the symbols of life and death before dates of birth and death is more preferred (the pentacle is most widespread to precede the date of birth), in Estonia the use of such symbols is more an exception than a rule.

A basic difference between the Finnish and Estonian tradition is the data of a living close relative (for example the spouse) on the grave marker. In Estonia it is possible: the gravestone may carry the name and the date of birth of the surviving spouse, in such case the date of death will be cut in later. In Finland such equalising with death is not customary.

Studying the epitaphs on the gravestones of the two countries it may be said that although in Estonia there are quite few of them (on Kärdla cemetery on 20% of all the gravestones, a figure is on 90%), in Finland there are no epitaphs in the general picture. Among the material I studied, epitaphs were on 3% of the gravestones, it is stated that in Helsinki as a whole 6% of gravestones carry them (Lempiäinen & Nickels 1990: 62).

At the Traditional history seminar Elle Vunder pointed to the preferences of the postmodernist society: the visual side that has started to dominate guarantees that information is quickly grasped and consequently quickly spread. Accordingly, the onset of visuality may be regarded one of the reasons why the longer textual part on gravestones is disappearing, while the figures show a tendency of generalisation.

Yet the generalisation of figures does not mean uniformity, here also certain differences can be detected: in Estonia the range of variety is wider, in Finland, however, traditions are followed more strictly. The most common symbol in both countries is still the cross, being more dominant in Finland (65% of gravestones with figures on them) than here (25%). Taking into account that in the year 1996 a total of 88% of the Finnish people belonged to the Lutheran church (Aho 1996: 121), it can be concluded that the wider spread of the cross among the Finns may be partly explained by their religious background, Finns may be regarded as more connected with the church and the religion than Estonians. Being a member of a congregation does not mean religiousness in itself, but the World Values Survey of 1996 revealed that even 57% of the Finnish people considered themselves religious, while only 14% of Estonians replied in a similar way (Liiman 2000: 10).

In the context of Estonia the use of the cross as a figure has not been studied in terms of time and space, that is why it cannot be stated that the use of the cross symbol on gravestones has started to decrease in years. Stonecutters say that although even now the cross is sometimes cut, it is mostly ordered by older people who are to some extent connected with the church (Viitamees 2001: 7). Comparing the spread of the Latin cross on Finnish and Estonian cemeteries and observing other symbols that are used beside the most frequent one (in Finland: a flame, the sun, an angel, birds; in Estonia: weeping birch, a candle, different branches, flowers), we may remark that the Finnish symbols arise much more from Christian implications than those in Estonia. Speaking of our preferences we should not forget our past. The deprecation, and partly prohibition, of everything related to Christianity will eventually, whether we want it or not, bring about the gradual changes in the mental world of people. Because of these shifts the sign systems on the gravestones of the two countries cannot be set in one-to-one opposition, drawing comparisons may prove to be quite conditional.

The abundance of figures on Estonian gravestones is justified by the increased picturesqueness of figures. On Finnish gravestones there are usually the joint images of the cross and the lily of the valley (the Finnish national flower), or the cross and ivy leaves, in Estonia we can find gravestones with whole pictures cut on them: trees, bushes, a house, a well in front of the house, a fence around the yard.

At the same time the use of the more 'generalised' symbols in Finland can be interpreted from the substantially different starting points of the gravestones in the two countries, proceeding from which the whole-family gravestone cannot carry so many details and characterise each person separately, but find a general expression, which prevents the stone from looking original. Not found in Finland, but rather typical in the symbolics of Estonian cemeteries is the image of the interrupted life of the deceased. Based on the material from Kärdla, it can be stated that it is usual particularly on the gravestone of a child or a young person. Most frequently the disruption of life is symbolised by a flower with a broken stalk, but there are also drooping flowers, like with lowered heads.

The symbols may be divided into groups that mark a specific age or sex and status. Thus on Kärdla cemetery the cross can mostly be found on the gravestones of women and spouses, the weeping birch has proved suitable for families, flowers for women and children, and symbols of the sea for men.

Because on the cemeteries of Finland personal gravestones form a relatively small and unimportant part, also the grave markers for a married couple are quite rare, we cannot draw such differences there. It is so that despite the fact that we may find figures from most gravestones in Finland and Estonia, and that epitaphs are disappearing or have disappeared from the general picture (see reasons for that Viitamees 2001: 7), the incriptions in the two countries have become quite different. There are several reasons for that, to some extent they have been explained above.

Where we are and where we are going

Cemeteries do not represent parts of society with inflexible customs and traditions, but as can be drawn from above, here also certain developments are on the way. The changes that are occurring or have already occurred on the selected cemetery in Helsinki can quite often be classified as processes arising from urbanisation. Together with urbanisation, visits to the cemeteries have been decreased, congregations have started to take care of the graves, death has turned into a publicly sold trademark. Visits to the cemeteries have fallen out of daily life due to several reasons: the tempo of life is ever quickening, the close ones who are buried in their former homeplaces may because of in-country migration remain even physically too far to be visited more often.

The size of the studied location is becoming more important, in larger places the collective knowledge resources are disappearing, dispersing, and so it is not possible to know without public advertising, where and how to order and arrange funerals and related services.

Visits to the cemeteries have began to drop out of people's everyday and Sunday routine, the decline of this need is particularly observable in Finland, where today it is not necessary for you to take care of the grave. While a neat-looking grave is a matter of prestige for urbanised people, this service is becoming a product in Estonia, too. Relatives mourn in their hearts and do not consider it necessary to do it at the grave. Often it is not possible any more either.

Yet, mourning and remembering the deceased in one's heart is not a new, urbanisation-related phenomenon, but a much earlier one. In the village society the intuitive behaviour was regarded more reliable, therefore probably the commemoration process that goes on in one's soul has not come forth.Cemeteries, the functions of which were earlier directed primarily to communication with the deceased, are turning into treasuries where the dead bodies are buried, but where one does not need to go to communicate with the dead person. Yet there are people who visit cemeteries even now and despite the quickening tempo of life, always find time to go for even a brief visit there. Or, namely because of the accelerating tempo of life, they feel the need to return to the place which is ruled by a completely different balance and fixed order.

Translated by Ann Kuslap

References:

Aho, Hannu S. 1996. "Ja sattu kerran, kun ne oli laskemassa arkkua hautaan…". Hautajaisaihe hautausmaatyöntekijöiden suullisissa kertomuksissa. - Kinnunen, Eeva-Liisa & Koski, Kaarina & Penttilä, Riikka & Pietilä, Minttu (toim.). Vitsistä videoon. Uusia kirjoituksia nykyperinteestä. Helsinki, Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, s. 137-155.

Heng, Bey 1999. Surutyökin muuttuu etätyöksi. - Helsingin Sanomat, 11. heinäkuuta, nr. 186, s. A 2.

HS I = Helsingin Sanomat 2000. Tunnustuksetonta hautausmaata on puuhattu vuosikymmeniä. - Helsingin Sanomat 29. huhtikuuta, nr. 117, s. B 12.

HS II = Helsingin Sanomat 2000. Hautausmailla ei monopolia. - Helsingin Sanomat, 29. huhtikuuta, nr. 117, s. B 12.

HSH = Helsingin seurakuntayhtymän hautaustoimi 1997-1998.

Hyvärinen, Irja 2000. Seurakunta laskuttaa 25 vuotta etukäteen hautanurmien hoidosta. - Helsingin Sanomat, 13. elokuuta, nr. 221, s. A 7.

Häiväoja, Heikki & Britta Nickels 1990. Vanhojen hautamuistomerkkien säilyttäminen ja kunnostaminen. - Lempiäinen, Pentti & Nickels, Britta (toim.). Viimeiset leposijamme. Hautausmaat ja hautamuistomerkit. Imatra, Sley-kirjat, s. 46-49.

Kiviharju-Wiebenga, Maikki 1997. Hyvin suunniteltu kuolema. - Helsingin Sanomat, 1. marraskuuta, nr. 296, s. D 3.

Lempiäinen, Pentti & Britta Nickels 1990. Muistomerkkien tekstit. - Lempiäinen, Pentti & Nickels, Britta (toim.). Viimeiset leposijamme. Hautausmaat ja hautamuistomerkit. Imatra Sley-kirjat, s. 62-67.

Liiman, Raigo 2000. Eesti elanikud ja usklikkus. - Postimees, 16. september, nr. 216, lk. 10.

Ots, Loone 1995. Annetus kalmule. Hauakirjadest Hiiu-Rahu kalmistul. - Köss, Tiia & Jaago, Tiiu & Tender, Tõnu & Västrik, Ergo (toim.). Vanavaravedaja, nr. 2. Tartu, Tartu NEFA, lk. 87-98.

S 2001 = Interviews with the gravestone markers of Tartu. Recorded by Triin Viitamees.

Valk, Ülo 1998. Inimene ja teispoolsus eesti rahvausundis. - Viires, Ants & Vunder, Elle (toim.). Eesti rahvakultuur. Tallinn, Eesti Entsüklopeediakirjastus, lk. 485-511.

Viitamees 2001 = Collected studi sources by Triin Viitamees.

Viitamees, Triin 2000. Kärdla kalmistu K-sektori hauapealdiste analüüs. Rahvaluule proseminaritööd 1999/2000. Manuscript in the University of Tartu, Department of Folklore.

Viitamees, Triin 2000. Suomalainen hautamuistomerkki Helsingin Malmin hautausmaan korttelin nr 54 perusteella. Soome keele seminaritööd 2000/2001. Manuscript is in the University of Tartu, Department of Estonian and Finno-Ugric Lingvistics.

Viitamees, Triin 2001. Kiviärist leiab nii lihtsa plaadi kui ka võimsa hauasamba. - Postimees, 11. mai, nr. 89. Tartu, lk. 7.

Yli-Kovero, Kristiina 1999a. Hautakivien hintoja vaikea vertailla. - Helsingin Sanomat, 2. marraskuuta, nr. 300, s. D 2.

Yli-Kovero, Kristiina 1999b. Vaatimattomuus väistyy hitaasti hautausmaalla. - Helsingin Sanomat, 2. marraskuuta, nr. 300, s D 1.