Family narrative as reverberator of history

Tiiu Jaago

At the end of the 1980s and the beginning of the 1990s when collecting folklore I came more and more into contact with an area of research that I began to study as family narratives. People talked about their daily life, calendar holidays, religion and singing to children in such a way that the narrator's own close relationships were reflected in it: when my mother died…; when I attended a wedding for the first time, my mother …; when I was in the army, my father …; my mother used to jig me so: …; when my mother got married, … On one hand the stories and pieces of information that follow the above phrases could be classified according to scientific canons into categories of folklore. On the other hand, in such a case the wholeness experienced in field study - the relationship between the experience of the speaker and the heritage - would get lost. This has led me to analyse the material from another point of view - the family narrative.

Family narrative marks a methodological aspect and does not set any thematic limits to the folklore under study. Through the stories and activities of the members of a group a family story is created (family history; calendar of family life, etc.), in which the family's sense of unity is shaped.

In the following one area of family narratives - family history - is analysed. This is closely connected with traditional history, while in these stories the group's sense of the past and the need to remember past things is reflected.

Story: a tale or a message from real life?

It can be inferred that the story involves different levels, three of which I would like to point out here: the levels of fact, interpretation and earlier tradition. On the fact level we learn what actually happened. On the interpretation level it becomes evident how the speaker experienced these events, why the speaker is talking of these specific events, what the importance of these events is for the speaker. The level of the earlier narrative tradition mirrors what can be talked and how it can be done. In order to narrate at all, there has to be certain experience in the heritage.

Stories about ancestors are realistic. But they also combine real facts with the levels of perceiving them. This is an essential basis for analysing family histories, because it often turns out that facts in oral tradition do not fully correspond to the fact in historical sources. Would the tradition prove wrong in such a case? (1)

The problem of the truthfulness of folklore is generally one of the most interesting ones in folklore studies. In narrative the limits of truth and fiction are far from being unambiguously defined. A traditional text, either oral or written, is connected with the reflection of reality, however, reality does not only consist of events and people, but also means of expression and earlier oral tradition. In this sense a fact-centred tradition is still a fiction of real-life events. (2) For a narrative researcher the question what happened is not as important as how these events are thought to have happened. Just in the latter case the importance of the speaker's point of view and earlier tradition basis comes forth in the scientific interpretation of the story.

In the following I would like to deal with subjects and opinions reflected in Estonian family narratives, more exactly in family histories.

My study is based on three central sources: oral narratives collected during fieldwork (MK); collections of written narratives Eesti Elulood (Estonian Life Stories - EE) and Suvun suuri kertomus (The Great Narrative of the Family - SUKU 1997) and written answers to the questionnaire Kodu ja pere (Home and Family - KV). The collection Ajaloolist traditsiooni (Historical Tradition) is based on thematic interviews from the 1920s-1930s and it is kept in Estonian Cultural History Archives (EKLA). Therefore not only written, but also oral narratives have been used; information presented both in the course of informal conversation and answering to questions; the structure of these texts is very diversified and exciting, but in this study this aspect will not be discussed.

Narrators from village community

The narratives of the 2nd half of the 20th century rest on two significant factors: the echoes of World War II (deportation; dispossession of homes; breach of the national balance, etc.) and urbanisation. In the materials collected from Estonia the first topic is dominant, but in the collection of Finnish family narratives the urbanisation-related matters come forward.

In the pre-World War II village community the history of founding the village and the family (household) history were intertwined. Knowledge from Tarumaa village and the Tarum family, collected in 1931, could serve as an example.

About the founding of Tarumaa village long time ago in the past the following information, which has survived in folk tradition to this generation, could be found.

There had been a village in Tarumaa already before the Northern War. Even today several signs give evidence of the early settlement here, for example a very old well with limestone walls, the bottom of the well cannot be reached with rods, the depth of the well is thought to have been 5 Estonian fathoms [about. 10.6 m.].

[---] During the Northern War the plague destroyed the whole settlement. In the entire Lüganuse parish only about 60 people survived. In Tarumaa village only one man stayed alive, his name is said to have been Hermann. He had found a wife from Nigula parish and had brought her with him. They had had three sons; the first had been named Jüri, the second Jüri, too. The first had been called Suur-Jüri [Big Jüri], the second Peen-Jüri [Thin Jüri], nothing is known about the name of the third son. The third brother must have died unmarried, but the two first brothers are the ancestors of the Tarums today. There are two groups of Tarums in Tarumaa - ones descend from Suur-Jüri, the others from Peen-Jüri. Suur-Jüri had a son called Mart; Mart had 4 sons: Jüri, Jaagup, Juhan and Priidik; Jaagup had 6 sons: Jaan, Priidik, Juhan, Mihkel, Kristjan, Joosep and daughters Leenu, Liisa and Miina. The latter, Miina, daughter of Mart-Jaagup, is the wife of the speaker, Anton Tarum, 5th generation, just like the Anton Tarum, who descends from Peen-Jüri. Peen-Jüri had a son Jaak, who had three sons: Mihkel, Jaan and Mart and daughters Mai and Mari, Mihkel had sons Mart and Juhan, Juhan had a son Jaagup and Mart had a son Mihkel and daughters Mari and Leenu. Mihkel's son's name was Mart, and he was the father of the speaker Anton Tarum. (3)

If the information is presented as a scheme, it becomes evident that all the details do not fit together: the speaker's wife is of the 6th generation, he himself of the 8th. This is a characteristic feature of genealogical charts that are based on memory - the 'convergence of time' (Jaago 1995: 112-113), which is revealed by some generations being left out of the list. Even a brief comparison with the data in the Historical Archives shows that the 18th century is outlined in the narrative according to the rules of life of the 19th century without accounting the extended family, and the complicity of the family and economic relationships in the family of that time.

The number of survivors of the 1710 plague in Lüganuse parish is by no means 60 as mentioned in the narrative, but this detail includes emotional information - a lot of people died. As a comparison: the recorded number of people killed in the plague is 1146 and the number of those who survived is 392, which is 25.5 per cent of the pre-plague population (Oja 1996: 237).

The narrative says that one man named Hermann survived the plague in Tarumaa village. According to the records of that time 12 people were killed by the plague in Tarumaa village and 4 people (2 married couples) survived. According to the 1712 survey there was no men named Hermann among them. Within thirteen-fourteen years the population had quadrupled, mainly through the birth of children, as the 1725-1726 ploughland records show that the population was 16 (four families). The Tarum family is related with Tõnn of Tõnne (Tenn of Tönnu), who is called Tõnn of Tarumaa in the records of 1739. At that time it was a scattered farm, not a village any more. Tõnn of Tarumaa had a son "Toomas, son of Old Tõno", who really had two Jüris in his family, one of them a farm hand. (4) It is possible that in the course of time the 18th century scattered farm developed into a small village, which is mentioned in the above sample text.

The above story includes some other typical features of village community family tree charts: (5) lines of male descent reach back to earlier times than female lines (women of earlier generations are not mentioned); the family is known according to the forefather's line; names contain part of the family tree (Mart-Jaagup's daughter Miina); typical is also the range of memory - five to seven generations, the time limit is the development of a new situation after the Northern War. The style of narration is also characteristic: what is not the direct experience of the speaker or what he evidently knows from stories, is often narrated indirectly, or the word 'probably' is used. (6)

Such stories of family history and the history of settlement have a local character: there are landmarks connected with the environment (for example, in this story, the well, but more can be sensed - obviously the speaker knows personally not only all the mentioned people, but he also knows their homes, their work in the field, etc.). Generations, who have lived in the same place for a long time are not only genetically related, but also have the same landmarks of memory, springing from either nature or lifestyle (same trees, same home, same way to church and graveyard, names; results of the work of many generations in the wood, field and buildings). It is considered important to point out in the story that people have lived in this place already 'before us'.

The above example is a typical story of a family who lived in the same place from the early 18th century to the 1930s. This is a community in which "unwritten rules and norms of behaviour had been fixed and become a common practice in generations" (ERM, KV 746, p. 373). It is essential that behind such knowledge is the respective tradition, for some reason all this has been important to be known. Those reasons are not revealed in the text, but as a rule they are syncretic by nature (i.e. having practical, e.g. legal, and emotional meaning and everything that is between or accompanying the two). But the fact that these stories were told presumes that through the narrative the listeners subconsciously learned to acquire and value the subjects handled in the story. In this respect the stories dealing with the history of family and home place not only convey knowledge from the past, but due to their selectivity, also create certain order for finding one's way in the world. Stable periods retain the order created by the stories, but when circumstances change, just the regularity level will be altered (Jaago 1995: 113-114; 119-121; Schmidt 1996: 67).

As seen above, the range of memory is substantially connected with the landmarks of memory. Those marks form a field of communication: where do you communicate and with whom, what is the material world like and the relationships between people. A peasant family history starts from the 'beginning' - founding a new place. Anything earlier was marginal: either referred to (The Mägins lived in Käva village all through the Northern War); carried along indirectly (names connected with the previous place of living are taken along into the new location) or the earlier ancestor story exists but has become ambiguous. This is caused by the existence or lack of direct contacts.

We can observe the alteration of the landmarks of memory in connection with moving home in the following example. There are two variants of stories of the ancestor's background to be compared. Both originate from the 1990s, from the representatives of the same family, but from different lines, which are not acquainted. The ancestor story starts from the second half of the 18th century, when they settled down in Kahula village, Virumaa. A hundred years later one observed family line left the place, the other line stayed in the family farm or in the neighbourhood until the first half of the 20th century.

According to the story the ancestor was exchanged for hounds after the Northern War. (7) The difference between the variants lies in that the line who stayed at home know the earlier location more exactly (Kerema village in Hiiumaa), they also know that the family name has been derived from the name of the home village in Hiiumaa. In the narratives of those who moved home at the end of the 19th century (8) the motive of exchanging for hounds is mingled with a motive of foreign origin (the ancestor was from Denmark or Norway and had been exchanged for hounds). Typical is that the change of home starts a new family story in their heritage: Since our family moved to….

Andres of Peedu

1736-1788

Laas

1766-1833

Mihkel

1792-1848Jaak

1806-1848Hindrik

1828-?Mihkel

1839-?Mihkel

1855-1905Jüri

1862-1900Rudolf

1882-1951Tiido

1895-?The ancestor was from Hiiumaa, he was exchanged for hounds and brought to Virumaa after the Northern War.

Three families are said to have come, 'our' ancestor was Laas.

When family names were given in the 1830s, the name Keremann was taken after the home village Kerema in Hiiumaa.

One of my early ancestors had been exchanged from Denmark or Norway for hounds. About our family settling down in Ridaküla, Viru-Nigula, it is said that my great-grandfather's father, who lived in Jõhvi Kahula village, bought farms for his three sons. The farm my great-grandfather Jüri K. got was the furthest from home.

Historical changes in society exert direct influence on family narrative. The above family history has been significantly shaped by the Northern War and its results, by serfdom, giving family names and buying farms.

Similarly the family narrative is affected by the changes due to urbanisation in the middle of the 20th century and the formation of an individual-centred world at the end of the century.

Knowing one's ancestors at the beginning of the 21st century: a question mark?

Narrators from the older generation very clearly sense the 20th-century changes in the family type: instead of the extended family that unites three generations, the small family starts to dominate. Even close relatives who temporarily live with the small family are regarded as separate from one's own family ('us'). (9) It is considered normal that grown-up children live away from their parents. It is stated that "everyone wants to be the boss in one's own house"; or "my home became a real home only when I got a home where I lived and was responsible for myself". (10) The narratives disclose the replacement of the dominating family type, for instance in a description of a conflict, where a 'commanding' father interferes in the young person's life too powerfully, limiting his/her freedom. (11) Attitude to parents' desire for authority is re-evaluated when the time passes, they are understood, but not complied with.

The right to be independent of one's parents and family, to be independent and individual, is deeply rooted in the society of the second half of the century. Thus the opposition - an individual or the member of a family - might be an intriguing topic for research in the egocentric world today. (12) Different ways of life change communication between generations and give a new look to family tradition.

Family narrative has become more personal. Now the focus is no more laid on knowing the line of ancestors or the results of their activities like the trees they have planted or houses they have built. One of the expressions of self-centredness is that one's (own) biography is mostly dealt with. Correspondingly, the family tree chart has been turned round. In the first half of the 20th century it really looked like a tree: the forefather and foremother as roots, their descendants-farmers as the trunk, and the contemporaries of the narrators-researchers as the branches. Today the starting point is the speaker himself and the family tree branches out towards the ancestors-roots. The earlier unity of the farm and ancestors has been replaced by the plenitude of roots that converge in the first person. This process is bilateral. On the one hand self-centredness is brought into consciousness, the hero of the story becomes more and more independent of his family. On the other hand the personal sphere becomes more public. Behind that process is the change in family structure: small families have begun to dominate instead of large extended families. Connections between generations and their interdependence have weakened because of changes in the demographic situation. (13) In the urbanising society the interrelations of generations have become different. An individual has become economically and emotionally more independent, he is an individual person and his acts are not to be measured by the acts of his family. At the same time the communication field has changed: with whom and by what means (diaries, letters, telephone, etc.) people communicate. The self-centred world allows privacy, but needs a new audience or, possibly, reading public. For example, in the memoir book of a schoolteacher from Läänemaa, born in 1890 there is a leaf explaining why he is writing it:

I am not writing these memoirs to make someone else feel warm, this is really impossible. But they may cause reactions in those who have had similar experience. And as childhood experiences are in many respects similar, it cannot be uninteresting to read about others' experiences of this period in a person's life.(14)

In 1953 a man born in Virumaa in 1905 begins his autobiography with the following argument:

For a long time already I have intended to put down my childhood memories, but I still haven't done it. I have simply been careless and indifferent, but in my ears I can still hear my late mother's words, speaking to me through tears of pain of those awful events that happened in our family, namely to my father. [---] Here I want to write down those events just as my late mother and my brother Ruudi told me.

He has a treasury of knowledge and memories, which have to be expressed. In 1970, briefly before his death he writes it again, but now giving a reason that is directed into the future:

I intended to start writing down my memories already long ago, but still I have put it off till better days. Once I even wondered if there is anyone interested in reading them. Perhaps there would not be any publishers for my book. So I nearly gave up the thought. But when my dear son repeatedly asked me to write my memoirs, which he seems to be interested in, I finally began writing today, on May 12, 1970 [---] in my beautiful home. (15)

The need to share one's experience is also revealed in the fact that a lot of people write their stories to various competitions. The written story is a characteristic phenomenon of narrative today not only because of the spread of literacy. More likely it is caused by the peculiarity of communication between close people in general and also the expansion of the private sphere as mentioned above. Heard stories cannot be orally reproduced for one reason or the other. Written stories contain also stories that have been heard earlier. The writer is aware that he cannot directly sense his readers, he cannot control them as the narrator can in oral tradition. On the one hand this sets certain limits to the narrator: he does not know the audience (if there is anyone interested…; hope that maybe it causes reactions in someone…). He must trust himself and the readers. The existence of such trust is an aspect that shows the broadening of the private sphere. On the other hand, at the moment of creating the author of a written story is more independent of his audience than the narrator of an oral story, who has to manage to utter it here and now.

Narrators today are not any more connected with their ancestors by the same home (farm), as a rule they are also representatives of different jobs - they are not related by similar jobs and experiences. Is it really significant at all to know your ancestors at the turn of the 21st century? If yes - for whom and why?

In principle I am of the opinion that being a member of the family is important today, too, but in another way than in peasant culture. The problem is therefore in eliciting the changes that have taken place in heritage process, not in denying them. The stories give evidence that people need real landmarks in time and space, and these are inevitably connected with ancestors. Experiences gained from childhood with parents help us get over difficulties. Home and family gave and continue to provide stability in the world that at times tends to sink into chaos. Reflecting upon the life of parents and grandparents and the relationships between family members proceeds from one's own life experience and the need for self-analysis.(16) The past exists for a person even if it is not evident at first sight. The narrator selects what is important for him in the scattered past and creates symbols, thus concentrating history in him and identifying his position in history. (17)

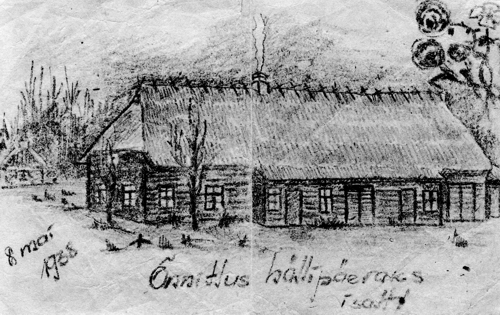

Birthday cards drawn in Siberia for the daughters: a memory of the lost home. Collection of Viiu Sinisaar. Such statements are first and foremost related to the analysis of oneself and of everything that goes on in the world in general, and family is seen as a small world within which the ABC of life is acquired. Everything that comes later is just placed on that base. Not always such opinions are revealed directly, where the narrator himself words his opinion of the significance of family. It may be reflected indirectly: the family teaches to behave and evaluate situations according to patterns. One man, for example, describes his father's death as seen through a boy's eyes, stating that mother had let it silently happen.(18) Describing the passing of parents or grandparents is quite usual in family narratives, and it is characteristic that such stories involve acquiring norms of behaviour in these critical situations.

The other reason for knowing heritage is its inevitability: if a person lives within such heritage, he simply knows stories of ancestors and he will not ask why. Ancestor stories belong together with childhood: "Father told me the history of our surname 'Wicht'"; "Mother said that grandfather had spoken how he had learned to smoke the pipe"; "Mother talked she had sung that song when she was a child". (19) These stories often have a fascinating plot, and they have a remarkable entertaining function.

Today tradition does not have any documentary function; consequently it does not have to be vitally known. Neither the procedures connected with the privatisation of farms and other property in the 1990s nor those related to the passport and citizenship will incite anyone to learn to know their ancestors better. But school and other institutions of public life (also the folklore collection competitions) may advance one's awareness of his ancestors and evaluation of such knowledge and inspire narration. In the following example the motivation for writing memoirs was a newspaper article. The memoir book is titled All that I sometimes recall…. The opening page presents a transcript of the article At the time of the formation of collective farms by Ervin Kivimaa, published in the Edasi newspaper on November 21, 1987. This was an early treatment of such subject in public. There is also a note from the transcription, partly underlined: "1066 kulak families were not deported, 956 of them were hiding (away from home), in 58 families only children were at home, 50 families were not deported because of the old age and illness of the members." For the narrator the note of the 58 families with children was important, because he classifies himself among these: "Most probably our family [---] belonged among those 58 families." The story continues with an account of the mass deportation in March 1949 from the point of view of their family's fate.(20) Such newspaper articles, photos, etc. can be interpreted as the current landmarks of heritage. Yet it is important that the existence of the narratives is based on earlier heritage.

The decrease of immediate experience is compensated by the opportunity to turn to written sources, including archive documents. The more family history can be studied on the basis of written sources, the more this sphere will move out of oral tradition. In Estonia it happened in the 1990s, as earlier, in Soviet times it was rather difficult for genealogists to access archival sources.

Foreign origin in family history:

- an indicator of social status or nationality;

- a subject related to legal relations and the range of memoryEven in the 1990s the ancestor stories of Estonian family narratives date back to the times of the Northern War, at the beginning of the 18th century. One quite widespread motive is the ancestor having come from Sweden or his Swedish origin. This tradition has undeniably started about 300 years ago. Why has it continued for such a long time? What does this motive mean today, when due to immigration during the last fifty years national balance has been severely damaged?

The biggest problems of Estonian society are the national groups here that have formed lately. Most of the difficulties are connected with their cultural and language identity and their career opportunities in their present homeland (Kirch 1999: 68).

Nationality question has been a crucial topic after World War II. (21) Tradition and genealogy do not display nationality problems and ethnicity unambiguously. At the beginning of Estonian genealogy in the early 20th century, nationality problems were acute. The study of the descent of the public figures of Estonian history was regarded as the aim of genealogy, in order to show their Estonian origin. At the same time the preference of the sample group seems just the opposite - they would rather be of Swedish descent.

And if it was definitely known about some of the ancestors [of important figures of Estonian cultural life] that that respectable man spoke German badly, the reason was that he had been a Swede! The quite natural idea that he could have been Estonian is scornfully rejected (Lipp 1909: 5).

Martin Lipp justifies such heritage, in which Swedish origin is preferred to Estonian one by the dominant mentality of the society at that time, which stressed that Estonians were the descendants of slaves and it was better to suppress it. Therefore the problem was rather a social one and people started to get over such understanding in the 1930s. One's foreign origin acquired an exotic colouring but excessively eager Germanophiles were derided.

A German student asks an Estonian student: "Listen, Mr. Saar, you are said to look very much like me - didn't your mother work for us as a maid? - No, baron, but my father worked for you as a coachman." And those who knew the relations between our countrymen and the manors knew that such possibilities were not much smaller than reproaches to the masters, but these were by far not regular occurrences (Hindrey 1931: 209-210).

National politics also influenced the request to the genealogy of the 1930s to show that instead of authentic German origin more often there was the Germanisation of local people (Perandi 1937: 164).

At the end of the 20th century the stories talking about the origin of ancestors do not reveal any traces of such national emotions although the motives are similar. It is evident that stories and notices of Swedish origin are topics that are (or have been) willingly cultivated, but being a child (or a descendant) of a manor lord has been a fact that the family has been aware of, but never a subject of narration (Jaago & Jaago 1996: 69).

At the beginning of the century as well as at the end of it Estonian society (and culture) is undergoing a breaking period - it is off the balance. Such unstable situation that is changing very quickly brings along fears that must be overcome. In connection with nationality problems the feeling of one's own group becomes stronger and the boundaries of different groups are defined. (22) But the difference in terms of ethnic and cultural survival at the beginning and the end of the century lies in the following: while at the beginning of the century the stress was laid on culture, now it is on nationality. Estonian culture had not been fully developed and did not offer possibilities for self-realisation on different levels (especially in science, politics). This caused social tensions. Now this problem has been done with. But if we observe the proportion of Estonians in the society at the beginning and at the end of the century, the situation is worrying, even more so because such situation has arisen as a result of aggressive politics.

Table: National composition of the territory of Estonia since the end of the 19th century (Palli 1998).

Year Estonians Germans Russians Swedes Jews Ukrainians

- Byelo-

- russians

Finnish (23) 1881 89.8% 5.3% 3.3% 0.6% 0.4% 1897 90.6% 3.5% 4.0% 0.6% 0.4% 1922 87.7% 1.7% 8.2% (24) 0.7% 0.4% 1934 88.2% 1.5% 8.2% 0.7% 0.4% 1959 74.6% - 20.1% - 0.5% 1.3% 0.9% 1.4% 1989 61.5% - 30.3% - 0.29% 3.1% 1.8% 1.1% 1997 65.0% - 28.2% - 0.17% 2.6% 1.5% 0.9%

At the beginning of the 20th century the subject of foreign origin was closely connected with the preference of social status. As a remark we should keep in mind that this is characteristic of urban, not peasant tradition. It is typical that the preferred foreign origin has traditionally been Swedish, despite the fact that archive sources do not confirm the Swedish descent of the forefather. So we may ask why such preference (ancestors have come from other places, which could have provided other origin patterns); and is this motive connected with national self-determination?

The migration of nations and contacts with other nations has continuously taken place on the territory of Estonia. At the beginning of the 18th century mostly immigration dominated, at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century - emigration, in the second half of the 20th century - immigration again. The pattern of Swedish ancestor is connected with the beginning of the 18th century - the period after the Northern War. At that time about 20% of the population may have come from our neighbouring territories, but mostly from Finland, Latvia and Russia and the descendants of village foreigners took over Estonian traditions within the 18th century (Palli 1998: 19-20). In this historical context the dominant Swedish origin in narration is especially remarkable. The motive of a Swedish forefather, which has formed as an echo of the events of the Northern War, is typical of the narratives of families with local lifestyle. The migration of peasants from one area to another was restricted and that is why until the national movement in the second half of the 19th century primarily the local identity prevailed. People were dependent on local nature and the respective geopolitical economic system, because of which their experience was similar to their ancestors'. In such a framework nationality question could not be relevant. It was the territorial and social frames that were essential. Nationality question arises in the ideology of the national state in the first half of the 20th century and in the conflict of the national politics of the Soviet Union in the second half of the 20th century. From the point of view of the described heritage the problem does not lie so much in nationality (they do not identify as Swedes) as in legal problems: whose home is here?; who has a right for this land?; who has lived here long?. After World War II those settled down in Estonia from the territory of the Soviet Union, are mostly town people. They lack the sense of unity with the land and work of ancestors, which is characteristic to peasants. They have also changed the country of residence - for their family the 'new start' is now, after coming to Estonia. The motive of Swedish descent in family history, however, allows dating the continuity of the generations not only to a Swedish ancestor but also to the 'Swedish times', which in Estonia ended with the Northern War (1700-1721). This oral history points out our bigger rights for this land, as compared with the rights of the newcomers favoured by the Soviet migration policy.

Conclusion

In the narratives today the nostalgic family tradition can be sensed as one layer. From the past something that is regarded as positive is chosen for the current time, as a rule it is related to the formation and creators of the welfare of the farm, which leads to the domination of male lines. The family schemes compiled in the 1930s on the basis of archive sources show preferentially male lines. As seen from the end of the 20th century the stories draw the alternating success of the life of families: the rise of prosperity in the 1930s, achieved through the hard work of ancestors, the prosperity which in its turn was followed by a setback in the middle of the century.

After the Second World War narratives have had an important role in Estonia in completing the gaps of official history. For example, active studying of local history, including the study of family histories in Kohtla-Järve helped to maintain self-consciousness in the new, post-war conditions, in which a town was founded in place of the village and immigration from the east (and not from the nearest parts) was considerable. (25) The cultivation of folklore was supported by the earlier strong tradition. Another aspect that favoured dealing with oral history in that period was the need for stability and security. Mostly by questioning family members family chronicles were compiled, but also female lines are accounted and stories as part of written chronicles are regarded as substantial, because they give a better picture of people and their life environment. At the same time the personality is handled differently: in agricultural society a person was valued through the family where he belonged to as an inheritor and contributor of his life work, now each person is observed as a separate individual. When characterising family relations, the axis leading from father to son and grandson as a depiction of continuity is replaced by the search of the roots of each individual. (26)

In 1990s the official (public) treatment of the history hidden in earlier times in Estonia expanded (incl. mentioning and studying ancestor stories in the media, at school, preparing family conventions, etc.). In this connection knowing ancestors exceeds the limits of folk narration, and enters the sphere of other forms of culture. Now it is possible to study one's family history on the basis of historical sources. The role of family narrative most evidently moves in the direction of recognising one's individuality (either in genetic or cultural sense). The forms of connection within a family as a tradition group have changed as regards the structure of the family, the same field of activity, etc. Together with this the symbols that earlier marked the unity are now disappearing (the farm, common home, graveyard, trees planted by ancestors, etc.) and new, more abstract and more individual symbols arise (for instance, some outward features or certain traces of character). The narrator and his roots are in the centre of tradition (not, for example, the farm and its builders). The form of expressing oral heritage has changed (beside oral narration written stories are starting to prevail more and more).

The generation of urban narrators is only developing, just as is the folkloric treatment of urban culture. The development of new forms of oral history takes about half a century: when the generation of grandmothers and grandfathers already represent urbanised culture, there is hope that we can study family history from the point of view of dominantly urbanised society. It is also possible that the tradition springing from the village community has dominated so far because it is noticeably receding. It is heritage that is not simply abandoned, but reinterpreted.

Translated by Kait Realo

References

Cultural Historical Archives in the Estonian Literary Museum (Tartu):

- EE - Eesti Elulood (Estonian Life Stories). Manuscript collection.

- EKLA - f. 200 m. 18, Oral history from the Lüganuse parish, collected by Marta Sorgsepp 1931.

Department of Estonian and Comparative Folklore of the University of Tartu:

- MK - Materials of Oral Family History. Manuscript collected by Tiiu Jaago.

Estonian Folklore Archives, Estonian Literary Museum (Tartu):

- ERA - The collection of manuscripts of the Estonian Folklore Archives (1927-1944).

- RKM - The collection of manuscripts of the folklore department of Estonian Acad. Sci. Fr. R. Kreutzwald Museum of Literature (1945-1996).

Estonian National Archives. Historical Archives (Tartu):

- EAA - f. 1228: EELK the foundation of Lüganuse parish congregation;

f. 1864: Collection of the inspection sheets of the Province of Estonia;

f. 3168: EELK the foundation of Pühalepa parish congregation.Estonian National Museum (Tartu):

- KV - Materials sent by correspondents. Manuscript collection.

Folklore Archives of the Finnish Literature Society (Helsinki):

- SUKU - Suvun suuri kertomus (The Great Narrative of the Family). Manuscript collection.

Eestimaa 1725.-1726. a. adramaarevisjon. Virumaa. Allikapublikatsioon. Tallinn 1988.

Hattenhauer, Hans 1995. Euroopa õiguse ajalugu. I. Tartu.

Hindrey, Karl August 1931. Tõnissoni juures. - Elukroonika V. Tartu.

Jaago, Tiiu 1995. Suulise traditsiooni eripära vaimses kultuuris. Peculiarities Oral Tradition in Intellectual Culture. - Pärdi, Heiki (ed.). Pro Ethnologia, No. 3. Tartu, pp. 110-121.

Jaago, Tiiu & Jaago, Kalev 1996. "See olevat olnud …" Rahvaluulekeskne uurimus esivanemate lugudest. Tartu.

Jaago, Tiiu 1996. On Which Side of the Frontier Are Trespassers? About the Identity of Ethnic Groups in Kohtla-Järve. - Valk, Ülo (ed.). Studies in Folklore and Popular Religion 1. Tartu, pp.181-195.

Kirch, Aksel 1999. Eesti etniline koosseis. - Viikberg, Jüri (koost. & toim.). Eesti rahvaste raamat. Rahvusvähemused, -rühmad ja -killud. Tallinn, lk. 68-71.

Koselleck, Reinhart 1999. Terror ja unenägu. Metoodilisi märkmeid ajalookogemustest Kolmandas Riigis. - Tuna. Ajalookultuuri Ajakiri, nr. 1, lk. 70-81.

Kreutzwald, Friedrich Reinhold 1953. Fr. R. Kreutzwaldi kirjavahetus. III. Tallinn.

Latvala, Pauliina 1999. Finnish 20th Century History in Oral Narratives. - Folklore. Electronic Journal of Folklore, Vol. 12, pp. 53-70. http://haldjas.folklore.ee/folklore.

Lotman, Juri 1999. Semiosfäärist. Tallinn.

Mälksoo, Lauri 2000. Keel ja inimõigused. - Akadeemia, nr. 3, lk. 451-474.

Oja, Tiiu 1996. Katk Põhjasõja ajal Eestis. Die Pest während des Nordischen Krieges in Estland. Zusammenfassung. - Artiklite kogumik Eesti Ajalooarhiivi 75. aastapäevaks. Eesti Ajalooarhiivi toimetised 1 (8). Tartu, lk. 217-253.

Palli, Heldur 1998. Eesti rahvastiku ajaloo lühiülevaade. Tallinn.

Perandi, Adolf 1937. Genealoogia senine viljelemine ja tuleviku ülesanded Eestis. - ERK, nr. 7/8, lk.161-165.

Sakkeus, Luule 1999. Migratsioon ja selle mõju Eesti demograafilisele arengule. - Viikberg, Jüri (koost. & toim.). Eesti rahvaste raamat. Rahvusvähemused, -rühmad ja -killud. Tallinn, lk. 310-325.

Schmidt, Andreas 1996. Die Poesie der Kultur. Ein Versuch über die Kriese der wissenschaftlichen Volkskunde. - Zeitschrift für Volkskunde, 92 Jg., I, S. 66-76.

Viikberg, Jüri (koost. & toim.) 1999. Eesti rahvaste raamat. Rahvusvähemused, -rühmad ja -killud. Tallinn.

References from text:

(1) Folklore has always had a reputation of untrue or improbable rumour. When the founder of Estonian folklore studies Fr. R. Kreutzwald was looking for a suitable term for folk tales in 1859, he considered a popular term - empty talk/story, which he did not favour himself (Kreutzwald 1953: 114). Empty talk or people say that … - evaluations of such type arise if only one level of the narrative is observed. Back

(2) Reinhart Koselleck (1999: 72) writes that the separation of fact from fiction is outdated in modern history science: "[---] our classical opposing pair res fictae and res factae is a gnosiological challenge even to historians today, theory-orientated and hypothesis-aware; [---] that it is namely the modern discovery of specific historical time, which ever since has urged the historian to prospective factual fiction, in case he wants to render the once-already-lost past." Back

(3) EKLA f. 200 m. 18: 2, pp. 49-50. Back

(4) Data from Kalev Jaago, archivist of the Historical Archives: EAA f. 1228; Estonian ploughland records of 1725-1726; 1988: 152. Back

(5) Cf. typical features of narrated family tree Jaago & Jaago 1996. Back

(6) The given sample is not the direct speech of the narrator, but the recorder seems to have had a good sense of narrative. Back

(7) The facts of this family narrative generally match the facts found in church records, although the fact of exchange for hounds cannot be proved. See more detailed: Jaago & Jaago 1996: 60-61.

At the same time such exchange for hounds was not rare in the 19th century Estonian tradition (for example the ERA card file includes related folk tales titled The Manor and the Peasant). This subject is also reflected in family narrative: for example ERA II 188, 435 (90), Käina 1938: "It is three-four generations back when my father's mother's father Siim of Proosu was exchanged for a hound [and sent] to Russia. He escaped a few years later." The exchange of peasants for hounds or the sales and purchase of peasants was possible during the era of serfdom, which lasted in the area of Estonia until 1816-1819. Until releasing from serfdom serfs did not have family names: before family names were given in 1820s-1830s a different surname system was used - surnames were derived from the first name of the ancestor or the master of the farm, or from the name of the farm, etc. Such sudden change of the surname system brought along a lot of folk tales and histories of family names. Releasing from serfdom and giving family names are connected with the opportunity of buying out farms in the second half of the 19th century. This involved the change of the earlier village structure and family type. In this case it is important that the former extended families began to split into separate large families; and search for their own home influenced the development of local migration and emigration. Back(8) The information presented in the table in Italics. Back

(9) KV 758: 135. Back

(10) KV 758: 120 (a woman born in Tartu in 1930); KV 758: 159 (woman, whose childhood home was in Tallinn, born in 1918). Back

(11) KV 758: 170 (a woman born in 1934). Back

(12) The appeal in the collection Suvun suuri kertomus (SUKU - The Great Family Narrative) includes this question. See also Latvala 1999. Back

(13) In the demographic situation in Estonia this trend started in the second half of the 19th century and the transition lasted until the 1930s. The change of demographic behaviour was expressed by the decrease in births and deaths and by family planning, as well as by constant population growth. It should be noted that this brought along the weakening of the connection between generations and local migration mainly from the country to county towns or towns at the turn of the 19th-20th centuries and also away from Estonia at the beginning of the 20th century (Sakkeus 1999: 312). Back

(14) MK: T. Back

(15) MK: K. Back

(16) SUKU 1997 39-42; 6651-6697; 7285-7300. Back

(17) SUKU 1997 7127-7139. Back

(18) EE 430, p. 166. Back

(19) KV 745, p. 170; p. 476; p. 478. Back

(20) MK: S. Back

(21) A survey of nationalities living in Estonia and problems connected with them can be found in the collection compiled by Jüri Viikberg Eesti rahvaste raamat (Book of Nationalities in Estonia), published in 1999, the quotation comes from this book. Back

(22) For example, the formation of relationships between nationality groups in Kohtla-Järve, see Jaago 1996. Back

(23) These are mostly Ingrians and Karelians from the territory of the Soviet Union, identifying themselves as Finnish. Back

(24) Differently from earlier times also the population of the Pechora region and the territory over the Narva River has been included. If we took the same territory as in 1881 as the basis, the respective figures would be 92% and 4%. Back

(25) In 1989 the proportion of Estonians in Kohtla-Järve was 19.7% (Palli 1998: 35-36). Back

(26) The difference of collective and individual concept of personality and the differences of the respective societies, see: Hattenhauer 1995: 49 seqq.; Lotman 1999: 13-14 (first 1992). Back