Man, woman and longings in Finnish village tradition

Tuija Saarinen

Recently, the research methods of micro- and mentality history have been introduced in folklore research. These methods allow us to treat topics, which were earlier unaccepted. These are themes formerly considered of lesser value or even taboo, such as sexuality or the life of common folk, exceptional individuals or minority groups (Heikkinen 1993: 21; Peltonen 1992: 10, 25, 61).

Exceptional persons differ from others because of their extraordinary way of life or actions and thus others pay attention to them and they leave traces in verbal tradition and documents (Tuominen 1999: 45). It is possible to characterise them by combining the information collected from different sources (Heikkinen 1992, 164; Heikkinen 1993, 27). My research topic is connected with an eccentric - a cobbler Juho Mäkäräinen, also known as Heikan Jussi (1892-1967) who lived in the village of Herrala in southern Finland. I will study his life history and the humour he created, as well as his contribution to the Herrala village culture. My sources of research are the interviews I have recorded in Herrala in 1989 with aged villagers who knew Heikan Jussi personally. (1) My informants included both men and women, but the material concerning sexuality is almost exclusively male tradition. Heikan Jussi's biographical and other information is confirmed by written documents like the biography Heikan Jussi himself wrote for the Finnish Board of Antiquities (Museovirasto), letters, postcards, diaries written by him, official documents (deeds of purchase, parish registers, etc.) and letters and postcards the other persons sent to Heikan Jussi. (2)

Heikan Jussi and the Village of Herrala

Heikan Jussi's home village is situated in southern Finland by the railway line between the towns of Riihimäki and Lahti. Herrala was a quiet and distant village in the municipality of Hollola until the construction of the railway was started in the 1860's (Heikkinen 1975: 31). Sawmill industry and other small-scale industries were set up in the village after the railway was completed and industrial workers moved there from other parts of Hollola and elsewhere (Heikkinen 1975: 374-375; Koskinen 1950: 35-36). One of them was Heikan Jussi's father Henrik Mäkäräinen, who was born in Sotkamo in the province of Kainuu in eastern Finland. Jussi's mother Natalia was of Herrala origin. Natalia and Henrik also had a daughter Anna Maria and a son Paavali, who died at the age of one. From her first marriage Natalia had two daughters, who were nearly adults when the younger children were born. (3)

Heikan Jussi caught tuberculosis when he was 12 and the disease directed his life ever since. (4) Before the discovery of antibiotics, tuberculosis was a very common disease in Finland and the mortality was high (Härö 1992: 184; Härö 1998: 10, 25). (5) Jussi recovered from the acute stage of the disease, but had to suffer from tuberculosis for the rest of his life. Because of it he had a hunch in his back and was never able to work enough to make a proper living but had to resort to his sister's financial help. (6) As a person suffering from an infectious illness he could not set up a family; at the beginning of the 1900s people suffering from tuberculosis were advised not to marry (Elmgren 1914, 18). His disability to work prevented him from supporting a family. "A handicapped or weak husband was a poor prop in a culture built upon physical performance", notes Satu Apo (1989: 170 - the author's translation).

Jussi did cobbler's work when he was in good condition. Besides this he sold for example candies, cigarettes and stationary in his hut. Due to these sources of income and his special sense of humour villagers often dropped in at his place. So it is probable that he never suffered from loneliness. (7)

Heikan Jussi's humour covered all aspects of life. His humour could be divided into verbal and practical humour (Radcliffe-Brown 1940: 195; Apte 1985: 115, 179). Verbal humour included witticisms or quotations from the Bible, linguistic tricks and nicknames for persons or objects (cf. Kuusi 1979: 373; Knuuttila 1992: 166; Tallman 1974; Apte 1985). Practical humour consisted of tricks. He also decorated his house and yard and his physical appearance and used objects in an unusual way, for example old hats to protect seeds from the frost at nights. (8)Jussi also moved and behaved as well as did his household work in a strange and personal way. (9)

Heikan Jussi had serious hobbies, too. He finished primary school at the age of 13, after having been absent for almost the whole school year because of tuberculosis, but he continued studying by himself. He completed his education by learning for example esperanto. He also read literature. Little by little he reached the status of a too wise person. (10) Besides studying he wrote articles for the local newspapers, took a great number of photographs and collected folklore which he sent to different archives. The regional history society of Herrala was established after Jussi's initiative in 1954 and he bequeathed his hut and all his property to the society. (11) Jussi's hut houses a museum today. The villagers paid much attention to Jussi already during his lifetime because of his qualities, hobbies uncommon for a villager and his conspicuous humour. After his death he gained recognition as the hero of a play, the subject of magazine articles and the Hollola regional yearbook, a topic of scientific research and the favourite hero of the village tradition.

Heikan Jussi's Sexual Humour

The interview material I have collected from the male inhabitants of Herrala village includes a great deal of sexual humour. I do not think that sex itself occupied the villagers' minds more than those of the average Finns, because there is a large amount of sexual humour in collections from different regions in Finland. (12) Both men and women have always told daring sexual jokes and these were known among the aged, too (Kaivola-Bregenhøj 1998: 200; Vakimo 1998: 307). Sexuality is a central area of life. Although it is a phenomenon belonging to private aspect of life, it also has a collective side because it in some way touches all human beings. Known and accepted forms of sexuality belong to the culture of any society (Pohjola-Vilkuna 1995: 12-13; Pohjola-Vilkuna 1993: 19). Folklore contains many ways to assess sexual norms of a person and a society (Kaivola-Bregenhøj 1998: 200).

Due to his tuberculosis Heikan Jussi never married. Only one possible bride of his youth is mentioned in my interview material. (13) There is only one unreliable allusion to her in Jussi's letters - which may also be a jest typical to Jussi. (14)

Although Jussi stayed unmarried, sexuality was not out of his mind. Jussi treated this subject in a humorous way and the male villagers told his jerks to each other. For example, it was told that he cut his pubic hair and wound it up into a ball. He told he would wipe the inner side of a drinking glass with this ball every time young women dropped in for lemonade he sold at his place. (15) It is not known whether he really did so or just amused himself with the idea, but it reminds us of the western form of Finnish love-magic, a contagious magic. It is based on the assumption that a relation will be established between two different objects (Piela 1990: 215; Stark 1993).

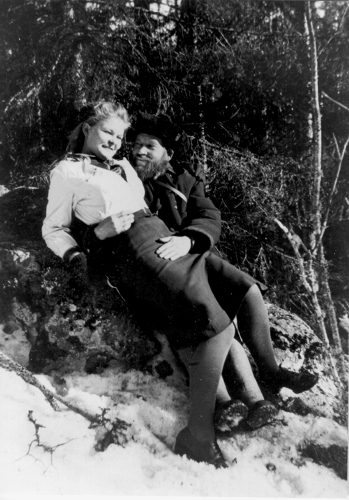

Heikan Jussi's sexual humour indicated his interest in women. While being around 50 during World War II, he photographed scantily dressed young women and even managed to photograph one naked.(16) Women posed voluntarily. The younger men of the village were in the war; hence posing may have offered young women a possibility to weigh their nascent femininity. Jussi also photographed mating cats, showed the photo to the irritated young girls and even sent it to a magazine to be published. (17) A male informant disapprovingly recalled how Jussi peeped at girls, (18) but none of my female informants admitted having been a victim.

Jussi Mäkäräinen and a young village girl during World War II. Photo Archives of Lahti City Museum Rneg 122000.

Heikan Jussi's verbal sexual humour was based on playing with double meanings of the language and words. When a young shop girl asked him: "What would Mr. Mäkäräinen have?", he answered: "I have the lust for flesh". (23) He always asked the shop girl for 16 cm of sausage (24) and may have implied to the male genitals, the size of which is a general object of joking (Anttonen, P. 1998: 383-386; Mulkay 1988: 132).

Women, sexuality and fertility are common themes in folk tradition. According to Veikko Anttonen, woman is an archetype for everything increasing as well as for critical turning points in primitive societies and agrarian cultures (Anttonen V. 1996: 139-140; Anttonen V. 1998: 138); folklore about female genitals is very frequent (see Apo 1995a: 22-23; Anttonen V. 1996: 8, 137). According to a widespread belief the female genital had strong power (Apo 1995a: 22-23, 63; see also Vuorela 1960: 84-88). Genitals are also the so-called symbolical sign indicating things with special social value. The vagina, which Heikan Jussi carved high in the tree, reminds us of a parallel found in the early folk belief. According to it, there is a connection between a female rut and a tree - especially a rowan. (25) The vagina, which Heikan Jussi carved in the tree above the heads of passers-by, could mirror his longing for a distant and unattainable woman - because the vagina was high in the tree where the penis, which was a plug in the flat-bottom row-boat, could not reach it. The unattainable vagina reflected also the respect and fear Jussi perhaps felt for women. Besides, the vagina represented a wife and fertility Jussi lacked. Sexuality and fertility became entangled as Jussi wrote to his unmarried sister:

Why must everybody like the herring tradesman have sons? What is it for them even to be run over by a train when they have a son continuing their lives? We have nothing. (26)

Annikki Kaivola-Bregenh¸j has noted that although a part of sexual tradition is common to different age groups, in questions concerning sexuality there are limitations. Sexual talk is common principally within age groups (Kaivola-Bregenhøj 1998: 208-209; see also Mulkay 1988: 122). The tradition of Heikan Jussi and his sexual humour is mainly humour of the male villagers and for a female interviewer it is possible to collect it only to a certain extent. It is told that in the literary notes left behind by Heikan Jussi there were verses of the so-called Kalevala of pornography (27) and notebooks containing songs with a sexual double meaning (the so-called songs of big boys). Unfortunately, they were censored before these literary notes were shown to the researcher or archived. Two male informants recalled of the existence of the songs and even a hint at them gave them great pleasure. They refused to repeat the verses when I was present. Excluding a woman from their tradition certainly strengthened their masculine identity and common solidarity. (28)

Humour, sexuality and portrait of Heikan Jussi

What is Heikan Jussi's sexual humour about? Popular eroticism is often straightforward and naturalistic (Apo 1995a: 64). The tradition I collected from the male inhabitants of Herrala village did not, however, describe 'real action'. Instead, the tradition expressed the sexual norms of the village and its ideas concerning the relation between a man and a woman, love or its absence, and fertility (Mulkay 1988: 141). Humour is one way to discuss sexual roles (Kinnunen 1998: 230). By talking about the sexual humour of Heikan Jussi the villagers of Herrala could express their own ideas and feelings of sexuality, which was in past decades a topic that people considered difficult or impossible to discuss in any other way.

In the village, the male informants maintain traditional ideas of sexuality by repeating Heikan Jussi's sexual humour.

Heikan Jussi's life was made up of different aspects, as it is with everyone. Jussi had several roles: a cobbler, a merchant and a village fool. He behaved differently in different social situations and with different people. The villagers who knew Jussi had each an individual impression of Jussi and this could differ from that of the other people.

The themes that informants or researchers focus on from the sources of Heikan Jussi can influence the creation of impression of Jussi. The humour dealing with sexuality was one example; it was a tradition of the male villagers and all of them did not even tell the same things. The impression of Heikan Jussi, that each informant of Herrala village had, was individual. Some of them did not even consider him worth the research at all, perhaps because of the sexual humour of bawdy form. However, the humorous behaviour of Heikan Jussi was what all the informants paid their attention to. His letters, diaries and other notes contained humour. Humour was the main reason why Jussi is still remembered decades after his death (Saarinen 2000: 99-100).

Sexuality, which I brought up in my article, was one of the themes in Jussi's humour. It gave a picture of Heikan Jussi as a person who was vigorous, boundaries breaking and eccentric. At the same time, the tradition underlined his loneliness since Jussi was joking about the intimate relationship between man and woman, which he himself lacked. Perhaps Jussi thus discharged the painful feelings loneliness caused him. Although one of the informants stated that Jussi had not suffered from loneliness, the lack of a partner and a family has been the central tragedy tuberculosis brought about in his life. The practical and verbal humour Jussi created is comical only if it is examined from the point of view of the public, the village society.

The sources telling us about Heikan Jussi's life show that he had a dual role in his village. On the one hand he was famous for his learnedness and he was a professional and important cobbler in Herrala. On the other hand he was known as a jester, whose role as a village fool established step by step until Jussi jested every time he felt it was expected from him. Jussi's behaviour was not randomly impulsive because he could behave well when he wanted to. His behaviour did not differ from the proper behaviour to the extent that could have caused him or any other person significant harm or damage.

The humour Heikan Jussi produced maintained the Herrala villagers' curiosity of him and talking about it could maintain the customs of the village, but it was also a way to discuss the topics people otherwise did not touch upon. The relationship between Heikan Jussi and the village society remained in balance and Jussi had a central role in his home village. Heikan Jussi died over 30 years ago but the humour he created is still a living tradition of Herrala. The tradition and the literal sources referring to Jussi tell us also about the present since the relationship between man and woman, love and longings are dateless subjects.

References:

Article "Heikan Jussin vaihtuvat kasvot". Hyvinkään Sanomat 25th July, 1998.

Communal Archives of Hollola (Hollolan kotiseutuarkisto):

- Anna Mäkäräinen's letter to Juho Mäkäräinen 21st July, 1942.

Juho Mäkäräinen's letters to Anna Mäkäräinen 27th June, 1913 and 29th July, 1935.The Finnish Board of Antiquities (Museovirasto):

- Juho Mäkäräinen's biography 14th August, 1964.

The Finnish Literature Society (Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura):

- The sound Archives of the Finnish Literature Society (SKSÄ - Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, Äänitearkisto). Interviews I have collected.

SKSÄ 88-89. 1989; SKSÄ 91-94. 1989; SKSÄ 98. 1989; SKSÄ 102. 1989; SKSÄ 105. 1989

SKSÄ 107-109. 1989; SKSÄ 114. 1989; SKSÄ 116. 1989; SKSÄ 119-120. 1989; SKSÄ 123-124. 1989; SKSÄ 127. 1989; SKSÄ 131-132. 1989; SKSÄ 134. 1989; SKSÄ 138. 1989; SKSÄ 141. 1989; SKSÄ 145-146. 1989.The Parish of Hollola: The Parish Registers 1852-1979.

Photo Archives of Lahti City Museum:

- Heikan Jussi's photo collection.

Literature

Anttonen, Pertti 1998. Seksistinen vitsi ja humoristisen kommunikaation poliittinen luonne. - Pöysä, Jyrki & Siikala, Anna-Leena (toim.). Amor, genus & familia. Kirjoituksia kansanperinteestä. Tietolipas nr. 158. Helsinki, Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, s. 367-396.

Anttonen, Veikko 1996. Ihmisen ja maan rajat. "Pyhä" kulttuurisena kategoriana. Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seuran Toimituksia nr. 646. Helsinki, Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura.

Anttonen, Veikko 1998. Pihlaja, naisen kiima ja kasvuvoiman pyhä locus. - Pöysä, Jyrki & Siikala, Anna-Leena (toim.). Amor, genus & familia. Kirjoituksia kansanperinteestä. Tietolipas nr. 158. Helsinki, Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, s. 136-147.

Apo, Satu 1989. Valistus ja viha. Lyyrinen laulurunous. - Nevala, Maria-Liisa (toim.). "Sain roolin johon en mahdu": Suomalaisen naiskirjallisuuden linjoja. Helsinki, Otava, s. 154-181.

Apo, Satu 1995a. Naisen väki: Tutkimuksia suomalaisten kansanomaisesta kulttuurista ja ajattelusta. Helsinki, Hanki ja Jää.

Apo, Satu 1995b. Pihlajista ja ukosta. - Hiidenkivi, nr. 5, s. 41-42.

Elmgren, Rob 1914. Voiko keuhkotautinen mennä naimisiin? - Terveydenhoitolehti, nr. 2.

Heikkinen, Antero 1975. Hollolan historia III. Taloudellisen ja kunnallishallinnollisen murroksen vuosista 1960-luvulta toiseen maailmansotaan sekä katsaus Hollolan historiaan 1940-1970. Hollola, Hollolan kunta.

Heikkinen, Antero 1992. Härän luut vuodassa. - Pitkänen, Pirkko (toim.). Menneisyyden merkitys. Historian suuret ja pienet kertomukset. Historian ja yhteiskuntaopin opettajien vuosikirja XXI. Joensuu, Historian ja yhteiskuntaopin opettajien liitto HYOL ry, s. 161-174.

Heikkinen, Antero 1993. Ihminen historian rakenteissa. Mikrohistorian näkökulma menneisyyteen. Helsinki, Yliopistopaino.

Hukkila. Kristiina 1992. Seksi ja Se Oikea. Tyttöjen ensimmäiset kokemukset ja käsitykset seksistä. - Näre, Sari & Lähteenmaa, Jaana (toim.). Letit liehumaan. Tyttökulttuuri murroksessa. Tietolipas nr. 124. Helsinki, Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, s. 56-68.

Hänninen, Jorma 1994. Seksitarinan pornografinen käsikirjoitus: minä sain, olen siis mies. - Roos, J. P. & Peltonen, Eeva (toim). Miehen elämää. Kirjoituksia miesten omaelämäkerroista. Tietolipas nr. 136. Helsinki, Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, s. 106-139.

Härö, A. Sakari 1992. Vuosisata tuberkuloosityötä Suomessa. Suomen Tuberkuloosin Vastustamisyhdistyksen historia. Helsinki, Suomen Tuberkuloosin Vastustamisyhdistys.

Härö, A. S. 1998. Tuberculosis in Finland. Dark Past - Promising Future. Tuberculosis and Respiratory Diseases Yearbook Vol. 24. Helsinki, The Finnish Lung Health Association.

Hyvinkään Sanomat 25.07.1998. Heikan Jussin vaihtuvat kasvot.

Joutsivuo, Tuija 1995. The Social Status of a Local Fool in a Finnish Village. - Kõiva, Mare & Vassiljeva, Kai (eds.). Folf Belief Today. Tartu, Estonian Academy of Sciences, Institute of the Estonian Language & Estonian Museum of Literature, pp. 164-167.

Kaivola-Bregenhøj, Annikki 1998. Pilako vai eroottinen viesti? - Seksuaaliarvoitus on testi kuulijalle. - Pöysä, Jyrki & Siikala, Anna-Leena (toim.). Amor, genus & familia. Kirjoituksia kansanperinteestä. Tietolipas nr. 158. Helsinki, Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, s. 193-215.

Kinnunen, Eeva-Liisa 1998. Pikku-Kalle ja kielletyt puheenaiheet. Rakkaus, sukupuoli ja perhe koululaisvitseissä. - Pöysä, Jyrki & Siikala, Anna-Leena (toim.). Amor, genus & familia. Kirjoituksia kansanperinteestä. Tietolipas nr. 158. Helsinki, Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, s. 230-249.

Knuuttila, Seppo 1992. Kansanhuumorin mieli. Kaskut maailmankuvan aineksina. Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seuran Toimituksia nr. 554. Helsinki, Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura.

Koskinen, Jaakko 1950. Herralan seudun asutuksen ja kehityksen vaiheita. Lahti, Lahden kirjapaino- ja sanomalehti-oy.

Laaksonen, Pekka (toim.) 1992. Mökkiläiselämää. Heikan Jussin kirjeitä ja merkintöjä Hollolasta 1903-1967. Kansanelämän kuvauksia nr. 37. Herralan kotiseutuyhdistyksen juhlajulkaisu. Helsinki, Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura.

Mulkay, Michael 1988. On Humour. Its Nature and Its Place in Modern Society. Padstow, Cornwall: Polity Press.

Paasio, Marja 1985. Pilvihin on piian nännit. Kansan seksiperinnettä. Helsinki,Otava.

Peltonen, Matti 1992. Matala katse. Kirjoituksia mentaliteettien historiasta. Tampere, Hanki ja Jää.

Piela, Ulla 1990. Lemmennostoloitsujen nainen. - Nenola, Aili & Timonen, Senni (toim.). Louhen sanat. Kirjoituksia kansanperinteen naisista. Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seuran Toimituksia nr. 520. Helsinki, Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, s. 214-223.

Pohjola-Vilkuna, Kirsi 1993. Vuosisadan vaihteen maaseudun seksuaalisuus. - Suomen Antropologi, nr. 3, s. 18-30.

Pohjola-Vilkuna, Kirsi 1995. Eros kylässä. Maaseudun luvaton seksuaalisuus vuosisadan vaihteessa. Helsinki, Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura.

Radcliffe-Brown, A. R. 1940. On Joking Relationships. - Africa XIII, No. 3.

Saarinen, Tuija 1999. "Hyvät voinnit, sukulai!" - Mäkäräisen Annun kirjeitä veljelleen Jussille 1941-1943. - Mantere, Heikki (toim). "Tehliäm mitä tehliäm, muttei ihlam mahlottomia." Hollola kotiseutukirja XIII. Hollola, Hollolan kotiseutuyhdistys r.y.

Saarinen, Tuija 2000a. Heikan Jussi. Katsaus kyläsuutarin huumoriin. - Krekola, Jani & Salmi-Niklander, Kirsti & Valenius, Johanna (toim.). Naurava työläinen, naurettava työläinen. Näkökulmia työväen huumoriin. Väki Voimakas nr. 13. Saarijärvi, Työväen Historian ja Perinteen Tutkimuksen Seura, s. 77-105.

Saarinen, Tuija 2000b. "Nyt on sitten sodat loppu." - Mäkäräisen Annun kirjeitä veljelleen Jussille 1944-1945. - Mantere, Heikki (toim.). "Kyl se käy kun uskuo vaa". Hollolan kotiseutukirja XIV. Hollola, Hollolan kotiseutuyhdistys r.y.

Stark, Laura M. 1993. "Lemmennosto ei ole syntiä mutta rakastuttaminen on" Gender, strategy, and social attitude in traditional Finnish-Karelian society. - Suomen Antropologi, nr. 3/1.

Tallman, Richard S. 1974. A Generic Approach to the Practical Joke. - Southern Folklore Quarterly Vol. 38, No. 4.

Tuominen, Marja 1999. Lukkari poikineen. Mikrohistoriallinen katsaus Kittilän seurakunnan vaiheisiin. - Tuominen, Marja & Tuulentie, Seija & Lehtola, Veli-Pekka & Autti, Mervi (toim.). Pohjoiset identiteetit ja mentaliteetit. Tunturista tupaan. Osa 2. Lapin yliopiston taiteiden tiedekunnan julkaisuja C. Katsauksia ja puheenvuoroja 17. Lapin yliopiston yhteiskuntatieteellisiä julkaisuja C. Katsauksia ja puheenvuoroja C. Jyväskylä, s. 45-73.

Vaikimo, Sinikka 1998."Vieläkö teillä tehdään yötöitä?" - vanhan naisen seksualisuuden kuva kaskuissa. - Pöysä, Jyrki & Siikala, Anna-Leena (toim.). Amor, genus & familia. Kirjoituksia kansanperinteestä. Tietolipas nr. 158. Helsinki, Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, s. 291-314.

Vuorela, Toivo 1960. Paha silmä suomalaisen perinteen valossa. Suomi 109: 1. Helsinki, Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura.

References from text:

(1) The interwievs are filed in the Sound Archives of the Finnish Literature Society (Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seuran Äänitearkisto) according to my former family name, Joutsivuo. When I refer to the interwievs I state the archive code given by the Finnish Folklore Society and the number of the table of contents. The average age of the informants was 63 years in 1989. Back

(2) The written sources are filed in the Archives of the municipality of Hollola and copied for the Folklore Archives of the Finnish Literature Society (Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seuran Kansanrunousarkisto). Pekka Laaksonen has edited Heikan Jussi's letters, which were published 1992 in a book Mökkiläiselämää. Heikan Jussin kirjeitä ja merkintöjä Hollolasta 1903-1967 (Laaksonen 1992). Heikan Jussi's sister's Anna Mäkäräinen's letters 1941-1943 were published in 1999 and letters 1944-1945 in 2000 (Saarinen 1999; 2000b). Back

(3) The Parish of Hollola, the parish registers 1852-1979. Back

(4) The Finnish Board of Antiquities: the biography of Juho Mäkäräinen 14th August, 1964. Back

(5) Tuberculosis in Hollola, see Forsius, Arno 1993: Sosiaali- ja terveydenhuollon kehitys Hollolassa ja Lahdessa vuosina 1866-1985. Lahden kaupunki. Lahti. Back

(6) The Finnish Board of Antiquities: the biography of Juho Mäkäräinen 14th August, 1964; SKSÄ 88. 1989, 2; Anna Mäkäräinen's letter to Juho Mäkäräinen 21st July, 1942. Back

(7) SKSÄ 91. 1989, 23; SKSÄ 105. 1989, 3; SKSÄ 107. 1989, 25; SKSÄ 08. 1989, 54; SKSÄ 109. 1989, 6; SKSÄ 119. 1989, 3; SKSÄ 123. 1989, 54; SKSÄ 124. 1989, 16. Back

(8) SKSÄ 92. 1989, 5. Back

(9) I have studied Heikan Jussi's humour in my unpublished M.A. thesis at the Department of Folklore of the University of Helsinki; see Heikan Jussin huumori Herralan kylän perinteen valossa (Heikan Jussi's humour in the light of the Herrala village). See also my articles "The Social Status of a Local Fool in a Finnish Village" (Joutsivuo 1995) and "Heikan Jussi. Katsaus kyläsuutarin huumoriin" (Saarinen 2000a). Back

(10) SKSÄ 102. 1989, 52; SKSÄ 89. 1989, 22-24, 27-29; SKSÄ 138. 1989, 14. Back

(11) SKSÄ 88. 1989, 6-7; Heikan Jussi's photographs (nearly 2000) are filed in the photo archive of the city museum of Lahti; SKSÄ 114. 1989, 23; SKSÄ 145. 1989, 66; SKSÄ 146. 1989, 23; SKSÄ 91. 1989, 21; The Finnish Board of Antiquities: the biography of Juho Mäkäräinen 14th August, 1964. Back

(12) See Paasio 1985: 16-17; sexual tradition is found in Lönnrot's notes as well, see Suomen kansan vanhat runot XV, 1997, XXXII. Back

(13) SKSÄ 138. 1989, 43-44; See also the newspaper article "Heikan Jussin vaihtuvat kasvot". Hyvinkään Sanomat 25th July, 1998. Back

(14) Juho Mäkäräinen's letter to Anna Mäkäräinen 27th June, 1913. Back

(15) SKSÄ 94. 1989, 32. Back

(16) There are many photos of this kind in his photo collection, for example the separate photos (irtokuvat) number 53-55. Heikan Jussi's photo collection, photo archives of Lahti city museum. Back

(17) SKSÄ 93. 1989, 69-70; SKSÄ 141. 1989, 44-45. Back

(18) SKSÄ 120. 1989; see also the article "Heikan Jussin vaihtuvat kasvot". Hyvinkään Sanomat 25th July, 1998. Back

(19) SKSÄ 93. 1989, 11-12. Back

(20) SKSÄ 131. 1989, 2. Back

(21) SKSÄ 93. 1989, 2. Back

(22) See Hänninen 1994: 122, 126-128. Starting a sexual intercourse functions as an initiation rite for girs as well - see Hukkila 1992: 57, 60. Also Kirsi Pohjola-Vilkuna has paid attention to the men's swaggering culture, in which coitus acts as a measure of the man's worth. Coitus has been culturally valued. (Pohjola-Vilkuna 1995: 105). Back

(23) SKSÄ 98. 1989, 2. Lihan himo ('the lust for flesh') in Finnish means both a desire for meat and carnal lust in a biblical sense of the word. Back

(24) SKSÄ 94. 1989, 42 Back

(25) Anttonen, V. 1998: 138; Apo 1995b: 41. Satu Apo has also mentioned that in the sexual fantasy poems sung by men a vagina, which is removed from the female body and animated: "… fence could fly in the air and land on to a field or it could travel in the forest and climb up a tree like a brown squirrel" (Apo 1995a: 16 - author's translation). Back

(26) Juho Mäkäräinen's letter to Anna Mäkäräinen 29th July, 1935. Back

(27) Kalevala is an epic composed by Elias Lönnrot from ancient Finnish poems. Back

(28) Article "Heikan Jussin vaihtuvat kasvot". Hyvinkään Sanomat 25th July, 1998; SKSÄ 93. 1989, 65. Back