Crooks and heroes, priests and preachers.

Religion and socialism in the oral-literary tradition of a Finnish-Canadian mining communityKirsti Salmi-Niklander

The goldmining center of Timmins and South Porcupine in Northern Ontario (Canada) is both a typical and a unique North American community. Like many other mining towns it was founded in the middle of the wilderness. Before the year 1909 the vast forests of Northern Ontario had been inhabited only by Native Americans, a few white trappers and gold prospectors. After the first gold findings the Porcupine Camp (1) grew very quickly into one of the largest goldmines in the Western hemisphere. The largest ethnic groups in the community have been the Finns, the Ukranians, the French, the Italians, the Croatians, and the Chinese (Barnes 1975).

The focus of my article is on the controversial relationship between religion and socialism as it has been discussed in the oral-literary tradition of the Finnish immigrants in Timmins and South Porcupine. I prefer the term 'oral-literary local tradition' to 'oral history' because I want to emphasize the interplay of orality and literacy rather than the opposition of 'oral history' and 'official history'. In immigrant communities 'official history' has often not been written and even official historical documents are scarce.

My source material includes handwritten newspapers from the 1910s and 1920s, manuscript local histories and interviews. Interplay of orality and literacy is typical of all the genres of oral-literary local traditions. Newspapers were written out by hand (most often as only one copy) but published orally, by reading them aloud at meetings. Written memoirs and local histories are based on oral narratives, but writers take distance from their own experiences. (2)

Parade of the Miners' Union in South Porcupine on May 1, 1913. National Archives of Canada/PA187072.

Dangerous truths and cover stories

I originally became interested in this remote community while reading the handwritten newspaper Ruoskija ('Whipper') at the Public Archives of Canada in Ottawa. This paper was written between 1912-1917 by the first Finnish inhabitants of Timmins, who worked as miners, cooks, and dishwashers.

Handwritten newspapers are a new kind of research material for both folklorists and historians. (3) They were a common tradition in Finnish (and Scandinavian/Estonian) popular movements at the end of the 19th century and during the first decades of the 20th century. (4) Handwritten newspapers gained new meanings in immigrant communities, where printed material was often scarce (Lindström-Best 1982). The Finnish community of tailors in Toronto had quite a sophisticated paper Toivo ('Hope') with political essays and short stories. Ruoskija contains material that is much more rough, but therefore especially interesting for a folklorist. Finnish miners describe frankly their life filled with hard work, gambling, and drinking, their fierce rivalry for the few Finnish women in the community, and longing for family life.

After doing archive research I made a field trip to Timmins in 1993. I stayed there for 10 days, and managed to interview quite a few very old Finns who had come to Canada during the 1920s or even earlier. My family and I were hosted and welcomed warmly by the Finnish community. However, I felt that many of the Canadian Finns were quite embarrassed that a researcher from Finland was interested in the rough early history of the community, and some seemed to think that this past was best forgotten. In the local tradition of the area - and in Canada as a whole - two stereotypical figures of a typical Finnish immigrant can be found: one is a communist and atheist troublemaker who lives in a common-law marriage and is constantly planning strikes and conspiracies against the government; the other is an alcoholic bachelor who lives whole his life in a boarding house and dies of either silicosis or heavy drinking, or commits suicide. Many Canadian Finns still experience these stereotypes as ethnic stigmata and do not want the shameful past to be retold, researched, or even remembered. (5)

These stereotypes are not total fallacies even though they present only one side of the picture. The Finnish immigrants in Canada were mostly left-wing whereas in the USA the right-wing 'church Finns' formed the majority immigrant group (Laine 1981: 5-6). Finnish religious activity in Canada stagnated during the 1910s and 1920s and the majority of Finnish immigrants were critical towards the church and the religion. The Finnish (Socialist) Organization of Canada (FOC) was the dominant political group until the 1930s. The paradox in this situation is that the majority of the Finnish immigrants came from Ostrobothnia, which has been a cradle for right-wing political movements and religious movements in Finland. (6)

According to Finnish-Canadian historian Varpu Lindström (1991: 182-183, 202-216) the background for the irreligiousness of the Finnish immigrants was the Finnish labor movement's criticism towards the Lutheran church at the beginning of the 20th century. In Canada Finnish immigrants were confronted with both a multiplicity of different religions and strict class conflicts. The religious situation among the Finnish immigrants was complex, as both the Presbyterian preachers of the United Church of Canada and the Lutheran priests were competing for the Finns´ souls. The Lutheran church wanted to keep up the national identity of the Finns, whereas the United Church aimed at encouraging the Finns to adapt the Canadian society, e.g., by organizing free English lessons.

Many Finnish-Canadian immigrants lived in common-law marriages. Reasons for this were both social and ideological: many Finnish immigrant men had left a family in Finland and could neither get an official divorce nor remarry; many of the socialist Finns refused to be married in church. "Canada is heaven for the women and hell for the men" is a common saying among the Finns, referring to the relatively small number of Finnish immigrant women. Alcoholism was a severe problem among many unmarried men. (Lindström 1991: 86, 102-105; Salmi-Niklander 1998a).

Some of the first Finns of Timmins on the threshold of their first society hall in 1911. National Archives of Canada/PA127078. These ideological controversies and social problems found their culmination in isolated multiethnic communities. The Canadian sociologist Peter Vasiliadis did fieldwork in the Porcupine area during 1980-1981. His reflection on his experiences in his book Dangerous truth (1989) gives many important points of view to a folklorist studying multiethnic immigrant communities:

It became evident that Timmins was a community of communities, often of a particular political, religious or nationalist orientation. Each individual had a "reputation" or clusters of reputations which varied according to community and situation. Individuals might have a reputation on a general community level and be perceived negatively as a "Communist troublemaker" by authorities and elite members while retaining a positive stereotype with the miners as a strong supporter of trade unionism. (Vasiliadis 1989: 22-23)

Vasiliadis cites a Finnish woman who was vehemently anti-Communist. In an interview she leaned close to him and confided: "You see the Communists - by the way are you a Communist? You could be for all I know and you could shoot me after what I said. Well, I'm telling the truth and the truth is sometimes very dangerous" (Vasiliadis 1989: 22).

According to Peter Vasiliadis these words point to a major methodological problem in the study of multiethnic communities. "The truth of record - especially within communities which had only recently begun to compete over historiography - is open to individual or group conjecture. What is an absolute truth for one individual or group is an absolute lie for another" (Vasiliadis 1989: 20-23). Vasiliadis points to the sparseness of written primary documents and to a "camp mentality" typical of communities such as Timmins: the residents perceive their stay to be temporary and assume that they will eventually be forced to leave. This leads to disinterest in both the past and the future of the community.

Another problem in research on multiethnic communities is that the existing documents are written in various languages. Vasiliadis himself could read neither Ruoskija nor many other texts written by the Finns in Timmins, nor could he interview those Finns who could not speak English. And there are quite a few Finns who have lived in Canada for most of their lives without ever learning English beyond the most basic everyday phrases. (7)

My own fieldwork experience was easier - and much shorter - than that of Peter Vasiliadis. However, I felt many times in my interviews that my informants did not tell me stories, legends or anecdotes, but 'dangerous truths', and sometimes they pointed this out to me directly. As a folklorist, I do not take dangerous truth so much as a methodological problem but as an object of research. I analyze how these truths are constructed, strengthened, or questioned with the help of narratives and rhetorical devices. Each dangerous truth has a countertruth or counternarrative which is constructed by those supporting the opposite ideological position. However, even though my objective is not to find out which one (if any) of the several contradictory dangerous truths is 'the real truth', I cannot totally cast out the problem of the validity of the narratives. Even though it is not possible to find out if a story is true or not, I can estimate if it is possible or probable. Of course it is interesting that even obviously impossible or improbable stories can be presented as the truth.

Another typical genre of the immigrant tradition is the 'cover story'. Immigration provided for an individual a possibility to create both a new future and a new past, a new identity for himself or herself. Sometimes this was necessary because an immigrant had escaped some shameful event, crime, or scandal, or a neglected a family in Finland. Cover stories were also created for ideological purposes. After the Finnish Civil War, during the 1920s, the members of the FOC established 'research committees' to investigate the activities of new immigrants during the Civil War. If someone turned out to have been fighting in the White guards, he was cast out from work groups and labor unions. (8) Dangerous truths and cover stories have been sailing back and forth between Canada, USA and Finland.

Red Finns and Church Finns

Local (amateur) history is a genre of writing which differs in many ways from the oral or written memoirs based on personal experiences. (9) Writers of local histories take the role of an objective historian by utilizing documents and making interviews, although often they do not indicate exact sources. Although writers of local histories have often participated themselves in the events they are writing about, they distance themselves from the events in their narration.

Viktor Koski and Isak Mäkynen were two Finnish inhabitants of the Porcupine area who took the role of a historian in the community and gave their manuscripts to the archives between the 1940s and the 1960s. (10) They represent opposite ideological positions: Viktor Koski was a devoted Communist who had fled Finland after the Civil War; Isak Mäkynen was a 'church Finn' and among the first members of the local chapter of the right-wing organization Loyal Finns of Canada (Suomalainen Kansallisseura) which was founded in 1931. (11) However, he was also mildly sympathetic to the labour movement. Both of these writers also describe such events in the history of the community in which they did not themselves participate. The local history they wrote was based on local oral narratives and their own interpretations of these narratives. The typed local histories written by Isak Mäkynen are compact and rather laconic. He rarely takes up his own experiences or opinions directly and sometimes even mentions himself in the third person. Viktor Koski is a totally different kind of narrator: he writes volubly and lets the story meander between the history of the community and his own experiences.

Greedy priests who crave after alcohol were a popular topic of caricaturists in Finnish immigrant comic papers. This brandy-loving priest is illustrated in the comic paper Lapatossu published in Hancock, Michigan, in 1912. The caption is a citation from a well-known Finnish hymn, which depicts a thirsty deer as a symbol of a Christian longing for God's love. Both of these local historians describe the birth of the Porcupine Camp and the Finnish community, Finnish miners arriving in the area during 1910 and1911, and the formation of the local association of the FOC during the great mine strike in 1912. (12) The first activities of the FOC in Timmins were writing the handwritten newspaper Ruoskija, building their own society hall - Isak Mäkynen praises the hall as "the first cradle of the Finnish culture in Timmins" - and starting a cooperative canteen.

Viktor Koski and Isak Mäkynen discuss the birth of the Finnish community in a retrospective perspective, while the handwritten newspaper Ruoskija provides a contemporary perspective to the same events. The language of Ruoskija is a combination of Ostrobothnian dialects, English words spelled in the Finnish manner, and an incorrect orthography. However, the writers describe their thoughts and experiences aptly and colorfully, although this is difficult to express in a translation. The following example in the Christmas issue of 1915 belongs to the genre of the 'mock sermon' which was popular in the Finnish workers' movement during the 1910s and 1920s. (13) The writer carnevalizes the Christian visions of heaven and hell with vulgar and mundane language full of references to eating and swallowing:

Oh my brother would not it be a valuable thing. Think if that great master would not have been just on Christmas born into the world, how would it be with our poor souls? Not any chance for salvation, nothing but the gaping gates of hell, which would swallow us with all our sins and hair. - Just think what a joy it would be in hell when small and big devils would tickle our ribs, and the whimpering and whining, my tongue is freezing in my mouth when I think about it ... but now it is different, all the joys and delicacies of heaven are open to us. There shall we get in plenty everything that we have not been able to enjoy here on the earth. There will be joy and delight, there will always be beautiful performances and tables full of the most wonderful delicacies, my mouth is watering when I think about the delicacies we will eat like pigs and what kind of miserable trash we have to swallow in this miserable world. Phew!

A third perspective on the early history of Timmins and South Porcupine is provided by Arvi Heinonen, a Finnish preacher of the United Church who held the first services in Timmins and South Porcupine in 1913. He describes his experiences (in the third person) in a leaflet published in English by the United Church, probably in 1917. Heinonen went from house to house, made announcements and gave invitations:

All the "Finn-towns" were aroused to see the Finnish minister, curses and tears of love were mingled, and in the last house visited in Timmins two children walked to a table to be baptized, while the Socialist boarders let blasphemy loose on the other side of the thin partition and pushed one another against it until the missionary every moment expected it to fall.

The mother of the baptized children comes to rescue the missionary, who continues his journey towards South Porcupine:

About half way they saw a number of whiskey-crazed Finns walking towards them and filling the road from side to side. Every man had a bottle in his hand and was swinging it in the air. The missionary made the horse gallop, thus compelling the men to divide and to let him pass. When he was passing, the crowd noticed his ministerial coat, and at once arose shouts of "pappi, pappi" ['minister' in Finnish] together with string of curses. After passing them, the missionary invited them to the service in their own language. They threw their whiskey-bottles at him but could not reach him. He thanked them for throwing away their bottles and promised to tell them of much better enjoyment if they accepted his invitation. So he left them to gaze after him.

Arvi Heinonen ([1917], 5-6, 9-10) is very critical of the Lutheran church in Finland, and provides in his leaflet his English-speaking readers reasons for the anti-religiousness of the Finns for his English-speaking readers: these are "the power of the clergy, especially regarding church taxes" and "the filthy and by no means Christian life that many of the clergy led".

Stories from the Bible were often reinterpreted in the socialist press and literature. The story of Jesus and Satan on the mountain is utilised frequently in the Finnish immigrant comic papers, but the characters in this socialist version are a worker and a capitalist. The caption of this cartoon published in the comic paper Punikki (New York 1931) begins with a direct citation from the New Testament followed by the words of the capitalist. He threatens the worker with deportation, but if the worker humbles himself before the capitalist, he will get a chance to die of hunger in this country together with his unemployed comrades. After Heinonen's short visit all religious activity stagnated in the Porcupine Camp for 15 years. The 1910s and 1920s were the time of prosperity for the FOC, which dominated the whole multiethnic community. The Workers Co-operative of New Ontario was founded by Finnish and Ukrainian socialists and it succeeded very well during the 1920s. At the end of the 1920s a political split took place in the Finnish community. The communists wanted to send a part of the profit of the co-op to Soviet Karelia where many Finnish communists moved during the 1920s and 1930s. This was too much for the more moderate Finns, who founded a competing company, Consumers Co-operative. They were organized into the Society of Workers and Farmers (Työläisten ja farmarien yhdistys), which built its own society hall named Harmony Hall. The ideological disagreement divided both the Finnish community and other ethnic groups for decades: the customers of Vörkkeri and Konsumeeri, the supporters of the FOC hall and Harmony Hall, lived separately and avoided each other as much as possible. The right wing church Finns also kept to themselves (Vasiliadis 1928: 124-130, 144-150, 166-169).

The Finnish Civil War affected strongly the Finnish immigrant communities during the 1920s, because many new immigrants had left Finland with bitter memories. The Civil War was discussed also in the handwritten newspaper Yritys ('Attempt') which was written by the Finnish Communist Development Society in South Porcupine in years 1928 and 1929. In issue 2/1928 a writer who takes the pseudonym 'A wife of a Red' (Punikin vaimo) discusses the White terror during the Civil War in her own (unnamed) home town in Finland in a story entitled Decennary Memories from My Native Place. A priest enters the story at the end:

In the place of murder there was also a priest. Why? Maybe to present his protest to the murder. Or to lead the souls of those going to their death towards a better life. Nothing of the kind, he was there to enjoy the bloodshed. Apparently the finest threads of the plot were in his hands, because he gave a speech on the grave saying that this event gives vivid proof that God exists. Did he suspect it earlier? He said the same the following day at the church. And he even went to preach in the prison cells.

A few months later this same priest went insane and he still is in a madhouse. Maybe he is still thinking the same: that God exists.

This story belongs to a legend tradition, which was very popular among the Reds after the Finnish Civil War. In these legends the murderers or their supporters get punishment later: they become insane, commit suicide, suffer from mysterious diseases, nightmares, or visions. Priests who accepted the Whites' killing of the Reds, or even participated in it, are main characters in many of these legends (Peltonen 1996: 223-231, 364-366).

Reverend Lappala - a crook or a hero?

The two Finnish preachers of the United Church, August Lappala and Arvi Heinonen, are central figures in the Finnish oral-literary tradition of the Porcupine Camp. They come up both in the manuscripts of Isak Mäkynen and Viktor Koski and in my interviews with some very old miners in 1993.

The religious activities in the Porcupine Camp were restarted in 1928 when another preacher of the United Church, August Lappala, came to the community. He became one of the leaders of the Loyal Finns of Canada (Suomalainen Kansallisseura), which was founded by the most right-wing Finns in 1931. During the 1930s Lutheran parishes were founded both in Timmins and South Porcupine (Pikkusaari 1947; Raivio 1975: 259-264).

One of the turning points in the history of the Porcupine Camp was the great fire in Hollinger mine in 1928. Thirty-eight miners, among them eight Finns, died. The funeral for the Finns became a political demonstration. According to Isak Mäkynen the FOC arranged the ceremony and denied the manager of the Hollinger mine attendance at the funeral. Instead of a funeral service a Finnish socialist leader gave a speech while dressed in a red sweater. Isak Mäkynen interprets this event as one reason for the system of "gatekeeping", which meant that during the Depression in the 1930s Finns could not get a job in the mines without a reference from the Finnish priest or without membership in the Loyal Finns of Canada (Vasiliadis 1989: 121-122).

The gatekeeping or 'card system' (korttisysteemi) as the Finns called it is the essential point in the stories about Reverend August Lappala. For Viktor Koski he was definitely a crook, a priest who got mixed up with politics and was enchanted by his power. Koski describes Reverend Lappala not just an agent in the gatekeeping system, but as one of its actual inventors together with a mysterious Colonel Elvegren. According to Koski, this Elvegren was a White leader and torturer of the Reds in the Finnish Civil War. He was supposed to have been killed by the bolsheviks in the Soviet Union at the beginning of the 1920s, but Koski had himself seen and recognized him in Toronto a few years later. (14) Koski mixes up historical concepts in his comment that Lappala and Elvegren invented a "Gestapo after the model of old czar Nikolai". According to Viktor Koski, an English-speaking priest of the United Church put an end to Lappala's gatekeeping and he was forbidden to get mixed up with politics.

If reverend Lappala is a prototypical crook for Viktor Koski, he is a prototypical hero for Isak Mäkynen. The following story about an FOC meeting in the year 1928 is obviously a recount of a meeting witnessed by Mäkynen himself, even though he keeps his own emotions aside until the last comment: (15)

At the same meeting had arrived a mother of two children, whose husband had gotten a job at the Hollinger mine, because at that time Hollinger mine did not employ the Finns, which was because of the outrageous propaganda of the Finns after the fire in Hollinger mine - 38 men died, 8 of them Finnish. This mother told the public how long her husband had been unemployed, she prayed God that her husband would get a job and turned in her distress towards Reverend Lappala and he was able to talk to the leaders of the Hollinger mine so profitably that her husband and the only supporter got a job. This woman spoke on the stage, the curtains were brought down but the woman stepped in front of the curtains and continued her speech thanking God and Reverend Lappala, then a group of men attacked the stage and roughly took this mother from the speaker's place (this was shocking for a young man from the old land).

Jalmari Saarinen (b. 1903), a miner and a contributor to several Finnish-Canadian newspapers, told to me in an interview a third dangerous truth about Reverend Lappala. He took this theme up voluntarily and apparently wanted to present his own argument, to disengage from the crook-hero composition in which Reverend Lappala had been placed by the Red Finns and the church Finns. He builds up his own, alternative position, describing the reverend as a decent priest and a decent man. The story is based on Jalmari Saarinen's own experience: he had been hurt in a mine accident and he had to fill in some applications for compensation in English. He did not want to pay for a professional translator but went to Reverend Lappala and was treated in a friendly manner:

When the paper was filled I asked: "What do I owe you for this?" - he was actually hurt, I am here to serve people, it does not cost anything. I said that this is a real man, a real pastor here. And I started to go to the little church at the corner of the Elm Street, one Sunday I went there, but they looked at me badly, somebody said that a communist dares to come here. I thought that I do not want to give offence to anyone and I stayed away, although I really liked it at the beginning.

Jalmari Saarinen remained a lone thinker, between the different ideological groups, and criticized in his newspaper articles the antireligiousness of the Finnish-Canadians.

Reverend Heinonen - a tragic hero or a silenced troublemaker?

Arvi Heinonen returned to the Porcupine Camp at the end of the 1930s. However, the official history of the Finnish-Canadian church neglects his later activities. Even though he was anything but a communist himself, his memory has been kept alive by members of the FOC. They present him either as a tragic hero or a sympathetic antihero.

World War II aggravated the political controversies of the Finns. The FOC was banned in the year 1940 but the next year, after Germany attacked the Soviet Union, the political situation turned upside down: now the right-wing Finns were treated as 'enemy aliens' by the Canadian Governement and the organization Suomen Apu ('Aid for Finland') was banned in turn (Vasiliadis 1989: 182-190; Lindström 2000).

Viktor Koski tells the story about an anonymous Finnish priest in his letter to the history committee of the FOC in the year 1947. According to Koski some "brawlers" came from Finland during the Winter War to recruit Finnish men for the war and to demand the banning of the FOC. An English-speaking doctor asked advice from the Finnish priests as to what he should do for those recruits who suffered from "certain diseases" (apparently venereal diseases). The priest advised to let them go to Finland. After this the priest was accused by the Finnish church of being a communist. "One fanatic" said that the priest was a communist because he went shopping at "the store of an enemy land" (apparently the Workers Coop):

The priest denied the charge and said that this is a legal store and he has to see where he can do his shopping advantageously, because his salary is small. Two people came to the church and the other one mentioned a Finn who is a communist leader (16) and who has called the priest a decent guy, so he had come to the conclusion that if that man praises the priest then the priest has to be a communist. The priest answered to the charge: I do not know that man well, but I know that this man has the best reputation among the Finns in Timmins, although you have given false information. The priest gathered his things and said: I do not put my finger into your fascist soup because it stinks and maybe it will burn you. The priest left and the church activity came to an end. He became a surface worker at a mine. I am almost sure that if there would had been an occasion in which one would have to die or to become a communist, this priest would have chosen the death.

In his memoirs Viktor Koski discusses Arvi Heinonen with his real name and constructs him even more clearly as a tragic hero. He also builds up a heroic past for him: according to Koski, Arvi Heinonen had been a school director in Finland, but fled to Canada in 1902, because he had actively opposed the conscriptions of Czarist Russia. This story is unsupported by existing documents and it is obviously inconsistent: if Arvi Heinonen had been a school director at the turn of the century, he would have been in his 80s or 90s during the 1940s when he had to go to work in the mines. (17) The story brings up again Viktor Koski's tendency to construct crook-hero characters and to revise historical events and concepts. In his stories Arvi Heinonen becomes an ageless and timeless tragic hero and a revolter against oppression.

Hannes Purra (b. 1902), a miner and a devoted supporter of FOC, told me a personal experience story about Arvi Heinonen in an interview. Hannes Purra had made friends with Heinonen when he worked as a taxi driver and brought many people to weddings and funerals. Later, in 1947, Reverend Heinonen became his workmate in the mine:He was [working] at Pamour [mine] after his parish came to an end, first in the carpenter shop to help the sawyer. It was Good Friday. We started teasing Heinos-priest: "How come a priest works on Good Friday?" He said that he has to support his folks. So he had a quarrel with the old sawyer and pushed him into the sawdust, so Heinonen had to work alone in a room to make sticks for firing. (18) He was put into an arrest.

Hannes Purra describes the humiliation of Arvi Heinonen with friendly irony, without explaining the reasons for his social downslide. He compares the jobs of a priest and a taxidriver, both having their own business. When Arvi Heinonen was already working in the mine, he still insisted that he wanted to marry Hannes Purra and his fiancée. However, when Purra and his bride got to the United Church, it turned out that Heinonen no longer had a permission to perform marriages. The irony of the situation is that Hannes Purra, a devoted communist who attended church merely because of his business as a taxidriver, seems to have been the last member of Arvi Heinonen's parish.

What was impossible for a priest or a preacher in the 1940s became possible in the 1960s. The Finnish Lutheran priests Pentti Murto and Markku Suokonautio worked for reconciliation of the different ideological groups in the community. Nowadays the conflicts are not longer active more as the early Finnish community had aged and the younger generation has become adapted to Canadian society.

Narration, ideology and gender

The stories about Arvi Heinonen and August Lappala demonstrate how narrative tendency (19) is dependent on both the ideology and the personality of the narrators. Viktor Koski takes the role of a historian but he writes in the manner of an oral narrator, builds up crook-hero-figures and mixes historical periods and concepts. This inconsistency makes his stories embarrassing and confusing, although he definitely is a good narrator. Isak Mäkynen keeps to the modest role of a local historian. The oral narrators, Jalmari Saarinen and Hannes Purra, describe the same events according to their own experiences and bring up their own personalities and ideological positions.

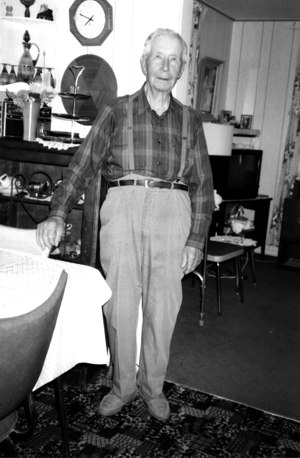

The Finnish miner Hannes Purra (born 1902) in his living room in South Porcupine in 1993. Photo: Margaret Kangas Why did preachers of the United Church become such controversial characters in the oral-literary tradition of the Finnish community? The Lutheran priests of the community did not become topics of a similar narrative tradition. The Finnish Presbyterian preachers were anomalies, since their position was very different from that of Lutheran priests in Finland, who had definite power in the community. The difference between the immigrant priests and the greedy and wanton Pastor Meno in Ostrobothnian legends analyzed by Anna-Leena Siikala (1984: 54-57, 75-81) is obvious. Immigrant priests were totally dependent on the members of the parish and they could fall from their social class. Reverend Lappala as described by Viktor Koski comes close to the 'slaughter priests' who accepted or actively supported executions and prison camps during and after the Civil War (Peltonen 1996: 223-231, 364-366).

In addition to ideology the priest/preacher stories discuss questions of masculinity. A frequent question is: Who is a real man, a decent guy? Is it he, who is sure of the absolute rightness of his ideology and does not hesitate to destroy those who think differently? Is it he, who has the courage to remain as an independent thinker if he is not accepted into any of the ideological groups? Or is it he, who wants to maintain friendship, interaction, and civilized behavior between different ideological groups even if this can be dangerous to his own life?

The corollary question is what were the stories of the Finnish women in the community. The Finnish women that I interviewed did not take up ideological controversies in a similar manner as the men. Varpu Lindström (20) has cited her interview with a Finnish woman, Miina Knutila, who was one of the first Finns in Timmins/South Porcupine:

At first I could only think of how to get away from Timmins; it was an awful place and then the fire destroyed whatever was left. But now, when I think of it, the beauty of the town did not lie in its buildings, in the mineshafts or in the muddy, impassable roads; it was in the hearts of the spirited workers and the women who worked together. We all shared everything. We cried together, we laughed together, we marched together, and we stuck together to the bitter end. I have no regrets, I never did find the gold I came to look for, but I did find a life full of purpose.

After reading all the previous stories on ideological conflicts it is hard to believe that this woman describes the same community. The stories of the Finnish men of Timmins and South Porcupine provide possibilities for questioning this touching story. When Miina Knutila talks about "us", the women and the spirited workers, does she mean only the members of the FOC, her own group? Did the solidarity of women cross ideological borders? In any case, her story should not be treated as a fallacy or a palliation. The refusal of bitterness is her dangerous truth and strategy for survival. Varpu Lindström has cited Miina Knutila's story at the end of her book on Finnish-Canadian women because it expresses not only individual memories or local history, but the experience of Finnish immigrant women in general. Similarly, the stories of Finnish miners can be read as universal narratives about struggle and division, courage and friendship.

References:Archives of Ontario, Toronto:

Memories of Viktor Koski:

- Kaisa Siirala Collection (KSR) MU 9915.01 MSR 7633 Ser. 062-027. I and II.

- L. Sillanpää Collection (LSC) MU 9915.04 MSR 8126 Ser. 062-030.FCHS - Finnish Canadian Historical Society:

Manuscripts "Kirkollista toimintaa Timminsin suomalaisten keskuudessa" and "Timminsin suomalaisten kirkollista toimintaa" MU 3355.04 Ser. 062-001 MSR 8361.

Finnish Labour Archives / Commission of Finnish Labour Tradition (Helsinki):

Memoirs K. V. Koski (92). (The originals of the memoirs in Archives of Ontario are included in this collection.)

Finnish Literature Society, Folklore Archives (Helsinki):

Interview of Hannes Purra (b. 1902), South Porcupine 12.5.1993: SKSÄ 134.1993.

Interview of Jalmari Saarinen (b. 1903), Timmins 6.5.1993: SKSÄ 130.1993.Public Arcives of Canada, Ottawa:

FOC - Finnish Organization of Canada:

Handwritten newspaper Ruoskija, Timminsin Suomalainen Sosialistiseura (Finnish Socialist Society) 1912-1919. MG 28, V 46, Vol. 51, F5-F8.Handwritten newspaper Yritys, South Porcupinen Kommunistinen Kehitysseura (Communist Development Society), 1928-1929. MG 28, V 46, Vol. 49, F14.

Local histories of the FOC chapters: MG 28, V 46, Vol. 92, F8.

Viktor Koski: "Ruokalan historiaa" & "Vapauden Viisikymmenvuotisjulkaisuun" (i.p.), Untitled letter 25.1.1948, "Timmins" 20.1.1948, "Timminsin Työläisten Osuusruokalasta" 18.2.1948, "Saunoista Timminsissä" 2.3.1948, Untitled letter 8.8.1965.Timmins Museum: National Exhibition Center:

Isak Mäkynen: "Porcupinen Kulta-alueen suomalainen historia, kokoillut Isak Mäkynen." #982.134.7.

Barnes, Michael 1975. Gold in the Porcupine! Cobalt, Ontario.

Besnier, Niko 1995. Literacy, emotion and authority. Reading and writing on a Polynesian atoll. Cambridge.

Eklund, William 1983. Canadan rakentajia. Canadan Suomalaisen Järjestön historia vv. 1911-1971. Toronto.

Finnegan, Ruth 1988. Literacy and orality. Studies in the technology of communication. Oxford.

Heinonen, Arvi I [1917]. Finns in Europe and in Canada. [1917]

Heinonen, Arvi I 1930. Finnish Friends in Canada. Toronto.

Helsingin Normaalilyseon matrikkeli 1887-1967. Helsinki 1967.

Iso Tietosanakirja III 1932. Helsinki.

Koski, Viktor 1980. The Journal of Viktor Koski, Timmins, Ontario. (Translated by Lindström-Best, V.). Seager, A. (ed.). Toronto.

Kostiainen, Auvo 1983. Suomalaiset siirtolaiset ja politiikka. - Kostiainen, Auvo & Pilli, Arja (toim.). Suomen siirtolaisuuden historia II. Aatteellinen toiminta. Turun yliopiston historian laitoksen julkaisuja 12. Turku, s. 83-135.

Laine, Edward W. 1981. Community in Crisis: The Finnish-Canadian Quest for Cultural Identity, 1900-1979. - Karni, Michael G. (ed.). Finnish Diaspora I: Canada, South America, Australia and Sweden. Toronto, pp. 1-10.

Lindström-Best, Varpu 1981. Central Organization of the Loyal Finns in Canada. - Finns in Ontario. Polyphony. The Bulletin of the Multicultural History Society of Ontario. Vol. 3, No. 2, pp. 97-103.

Lindström-Best, Varpu 1982. Kanadansuomalaiset nyrkkisanomat. - Ulkosuomalaiset. Kalevalaseuran vuosikirja 62. Helsinki, s. 27-33.

Lindström-Best, Varpu 1989. Finnish Socialist Women in Canada, 1890-1930. - Kealey, Linda & Sangster, Joan (eds.). Beyond the Vote: Canadian Women and Politics. Toronto.

Lindström, Varpu 1991. Uhmattaret. Suomalaisten siirtolaisnaisten vaiheita Kanadassa 1890-1930. Porvoo-Helsinki-Juva.

Lindström, Varpu 1997. Ethnocentricity and Taboos. - Untouched Themes in Finnish Canadian Social History. Melting into Great Waters. Papers from Finnforum V. Special issue of Journal of Finnish Studies Vol. 1, No. 3, pp. 33-47.

Lindström, Varpu 2000. From Heroes to Enemies. Finns in Canada 1937-1947. Beaverton, Ontario.

Numminen, Jaakko 1961. Suomen nuorisoseuraliikkeen historia I. Vuodet 1881-1905. Keuruu.

Peltonen, Ulla-Maija 1996. Punakapinan muistot. Tutkimus työväen muistelukerronnan muotoutumisesta vuoden 1918 jälkeen. Helsinki.

Pikkusaari, Lauri T. 1947. Copper Cliffin suomalaiset ja Copper Cliffin Suomalainen Evankelis-Luterilainen Wuoristo-Seurakunta. Hancock, Michigan.

Pilli, Arja 1983. Amerikansuomalaisten kirkollinen toiminta. - Kostiainen, Auvo & Pilli, Arja (toim.). Suomen siirtolaisuuden historia II. Aatteellinen toiminta. Turun yliopiston historian laitoksen julkaisuja 12. Turku, s. 9-55.

Raivio, Yrjö 1975. Kanadan suomalaisten historia I. Copper Cliff.

Raivio, Yrjö 1979. Kanadan suomalaisten historia II. Thunder Bay.

Salmi-Niklander 1996. Lennart ja Fanny Lemmenlaaksossa. - Rahikainen, Marjatta (toim.). Matkoja moderniin. Helsinki, s. 117-138.

Salmi-Niklander, Kirsti 1997a. "The Enlightener" and "The Whipper". Handwritten Newspapers and the History of Popular Writing. - Elore, No. 2: http://cc.joensuu.fi/~loristi/2_97/sal297.html

Salmi-Niklander 1997b. "Varoka ihmisijä joiren jumala on taivasa". Uskonto ja työväenliike kanadansuomalaisessa kaivosyhteisössä. - Parikka, Raimo (toim.). Työväestö ja kansakunta. Väki voimakas 10. Helsinki, s. 27-67.

Salmi-Niklander, Kirsti 1998a. "Isot poijat ne koppasee..." Siirtolaiserotiikan terminologiaa ja kipupisteitä. - Pöysä, Jyrki & Siikala, Anna-Leena (toim.). Amor, Genus & Familia. Helsinki, s. 278-290.

Salmi-Niklander, Kirsti 1998b. "Maailman parhaat kulkuneuvot". Matka ja muutos Karkkilan paikallisperinteessä. - Hänninen, Sakari (toim.). Missä on tässä? Jyväskylä, s. 42-70.

Salmi-Niklander, Kirsti 1999. Soot and Sweat. The Factory in the Local Tradition of Karkkila. - Hänninen, Sakari & alii (toim.). Meeting Local Challenges - Mapping Industrial Identities. Papers on Labour History 5. Helsinki, s. 130-142.

Seager, Allen 1981. Finnish Canadians and the Ontario Miners' Movement. - Finns in Ontario. Polyphony. The Bulletin of the Multicultural History Society of Ontario. Vol. 3, No. 2, pp. 35-45.

Shuman, Amy 1986. Storytelling rights: the uses of oral and written texts among urban adolescents. Cambridge.

Siikala, Anna-Leena 1984. Tarina ja tulkinta. Tutkimus kansankertojista. Helsinki.

Sintonen, Teppo 1999. Etninen identiteetti ja narratiivisuus. Kanadan suomalaiset miehet elämänsä kertojina. Jyväskylä.

Street, Brian V. 1984. Literacy in Theory and Practice. Cambridge.

Suokonautio, Markku 1984. Reorganization of the Finnish Lutherans in Canada. - Finns in Ontario. Polyphony. The Bulletin of the Multicultural History Society of Ontario. Vol. 3, No. 2, pp. 91-96.

Vasiliadis, Peter 1989. Dangerous Truth. Interethnig Competition in a Northeastern Ontario Goldmining Center. New York.

Wargelin, Raymond 1972. Finnish Lutherans in Canada. - Jalkanen, Ralph J. (ed.). The Faith of the Finns: Historical Perspectives on the Finnish Lutheran Church in America. Michigan.

References from text:

(1) Peter Vasiliadis (1989: 19) uses the term "the Porcupine Camp" for the city of Timmins and the other smaller towns and municipalities in the area (South Porcupine, Pottsville, Schumacher). According to Vasiliadis, this term is "a leftover from the inception of the mining base in 1909 but of symbolic importance to the present". Back

(2) The concept of the oral-literary local tradition refers to the discussion on orality and literacy by Brian Street (1993) and Ruth Finnegan (1988). The analysis of oral-literary practices has been inspired by Niko Besnier (1995) and Amy Shuman (1986). Back

(3) Ruoskija is comparative material in my forthcoming doctoral thesis in folklore studies, which focuses on the oral-literary local tradition in Karkkila, a Finnish industrial community (Salmi-Niklander 1996, 1998b, 1999). This article is based on a longer article published in Finnish (Salmi-Niklander 1997b). Back

(4) Handwritten newspapers originate from newsletters, which were common during the 17th and the 18th centuries in Europe. Handwritten newspapers were produced in aristocratic and bourgeois families, schools and universities starting from the beginning of the 19th century (see Salmi-Niklander 1997a). Back

(5) Varpu Lindström (1997) has discussed the untouched themes and taboos in Finnish Canadian social history. Back

(6) On political activities of the Finnish Canadians, see Lindström 1991: 220-226, 233-234, 246-247; Kostiainen 1983. On religious activities, Lindström 1991: 184-192, 198-199; Pilli 1983; Suokonautio 1981; Wargelin 1972. Back

(7) Incompetence in speaking and reading English was common among those Finnish immigrants who arrived in Canada before the Great Depression in the 1930s. Those Finnish immigrants who arrived after World War II are more competent in English, which has created tensions between different generations of immigrants (Sintonen 1999: 161-167). Back

(8) Yrjö Raivio (1974: 464-485) discusses this period in his book on the history of the Finns in Canada. His point of view comes close to that of the "church Finns". Back

(9) Ulla-Maija Peltonen (1996: 60-133) has discussed the writing narrator in her research on the personal memoirs from the Finnish Civil War 1918. Back

(10) Several large manuscripts by Viktor Koski (b. 1898) are preserved both in the Workers' Archives in Helsinki and in the Ontario Archives in Toronto (as copies). He has also written several manuscripts on the history of the Porcupine camp for FOC (Public Archives of Canada). - Isak Mäkynen has given a manuscript entitled The History of the Finns in the Porcupine Goldmining Region to the Timmins Museum. Also two manuscripts on the religious activity among the Finns in Timmins (Finnish Canadian Historical Society, Ontario Archives, Toronto) have probably been written by him. - The manuscripts of Viktor Koski and Isak Mäkynen have been utilized by other researchers. Viktor Koski's memoirs have partly been translated into English (1980). Allen Seager (1981) and Peter Vasiliadis (1989) have used it as source material. Manuscripts by Isak Mäkynen have been utilized in the history project of Finnish Canadian Historical Society (Raivio 1975: 259-264; Raivio 1979: 269-270). Both the FOC (Eklund 1983) and the right-wing Finns (Raivio 1975, 1979) have had their own history projects. Back

(11) Activities of Loyal Finns of Canada have been discussed by Varpu Lindström-(Best) (1981). Back

(12) During World War I the word 'Socialist' was left out from the name, so thereafter it was the Finnish Organization of Canada. FOC joined the Communist Party of Canada soon after it was founded after World War I (Lindström 1991: 246-247). Back

(13) 'Mock sermons' in the Finnish labor movement have been discussed by Ulla-Maija Peltonen (1996: 218-219). Back

(14) The model in Colonel Elvegren is probably lieutenant-colonel Yrjö Elfvengren (1889-1927). According to the encyclopedia Iso Tietosanakirja III (1932) he led the Karelian regiment in the Finnish Civil War and fought against the bolsheviks in Ingria at the beginning of the 1920s. Elfvengren went to the Soviet Union in 1925 working as a spy and a terrorist against the Soviet government, until he was executed by the secret police. Back

(15) The same story is repeated in both manuscripts by Isak Mäkynen. Back

(16) In another version of this story sent to the Finnish Labour Archives in 1958 (K. V. Koski 92/26D, pp. 121-125) Viktor Koski indicates that the Finnish communist leader mentioned in the story was Koski himself. Back

(17) According to the school enrollment book of a secondary school in Helsinki (Helsingin normaalilyseon matrikkeli), Arvi Heinonen was born in Helsinki in the year 1887 and died in Ontario in the year 1963. Back

(18) Hannes Purra uses an American Finnish word savitänkkitikkuja, but I have not been able to find out the exact meaning for it. He explains that they were some kinds of sticks used for firing guns or canons. Back

(19) On the concept of narrative tendency see Siikala 1984: 96-97; Peltonen 1996: 57. Back

(20) The citation has been published both in Finnish (Lindström 1991: 271 ) and as an English translation (Lindström-Best 1989: 213). Back