Departing from this life.

Changes in death culture in Estonia at the end of the 20th centuryTiia Ristolainen

Introduction

Death is one of the most important problems that all people face. Death is a vital moment of transition from earthly life into the eternal post-mortal state. So it is only expected that there was and is a variety of beliefs and customs related to death in Estonian folk religion, reflecting people's understanding of life in different eras.

In her earlier studies the author of this article has concentrated on the 19th - beginning of 20th century death-related tradition based on the sources of Estonian Folklore Archives. In the first half of the 20th century the rural community was dominant in Estonia. In the second half of the century active urbanisation can be witnessed. First, rural people went to towns to escape from the kolkhozes and sovkhozes that were founded in their local neighbourhood. The immigration of people from different places of the Soviet Union into Estonia also concerned towns mostly. Secondly, the rural community was also urbanised through modern technical devices, residential blocks, mass communication, etc. In order to compare the culture of death in the rural community and in modern life, the author has collected death-related folk tradition in the 1990s in Northern Estonia, in the coastal villages of the Bay of Finland, in Rakvere (Northern Estonia), and Tartu (Southern Estonia) and together with the folklore students from the University of Tartu on the largest Estonian islands: Saaremaa and Hiiumaa.

Comparing the old (archive sources) and new (field trips) material, several changes can be detected. This article aims to find an answer to the question, to what extent and under the influence of what aspects these changes have taken place and what the future trends of death culture might be.

What is death culture?

In modern society the culture of death does not relate to mythological conceptions, but it also involves legal, medical, psychological and other individual aspects of today's culture. In the village community these were naturally connected with tradition. Such synthesis of different areas in its turn requires the interdisciplinary treatment of the subject of death culture. In the following the author has primarily proceeded from the points of view of the study of religions, but also from the general theory of folk tradition. Today in the research of folk religion, death-related topics are not handled in a restricted way, but extensively, joining all the areas under the common denominator 'death culture'. In the following various definitions of culture and death culture are observed to find a definition suitable for the Estonian tradition.

Lauri Honko and Juha Pentikäinen have treated this subject in their review of cultural anthropology published in the 1970s as follows: "Culture in its essence is acquired behaviour, a series of patterns and schemes, which guarantee the survival of an individual and a society in the sphere of practical mutual influence that at the same time promotes integration." E. A. Hoebel is quoted: "Culture is the integrated, unified whole of the acquired modes and patterns of behaviour, characteristic of the members of society, and of the results of such modes and patterns. Culture survives only through the exchange of information and studying; in short - it is not based on intuition." One more key word is added to the above - tradition. "Although culture is mainly expressed in the behaviour of individuals, in a certain sense it is still above the individuals. [---] The dominating position of collective tradition ensures that an individual who is born and finds his place in the society does not create or develop his culture, but culture creates and develops him" (Honko & Pentikäinen 1997: 11).

The definition given in the Estonian Encyclopaedia lays the stress on the social meaning of culture:

[---] Human culture as a whole can be treated as an information system, in which socially meaningful experience is recorded, stored and transferred from individual to individual, and from generation to generation by non-genetic means. [---] Culture is something with a social meaning, i.e. something recognised, understood, appreciated, and generally accepted in the specific social group. [---] Culture in its essence is the collection of knowledge, values, norms of behaviour, beliefs, codes of style and other phenomena that express the intellectuality of social life; a collection which can socially act only in a material form, i.e. intermediated by certain people through certain social relationships and institutions, shaped in material environment and languages. (EE 1990: 202)

By the semiotic-typological way of research, culture may be defined as follows:

- Culture can be observed from inside, therefore it is a confined area and contrasts to cultures that are outside of it. Culture - non-culture. If it is held absolute, it seems that culture does not need anything outside of it and is inherently understandable;

- The definition of culture from outside. Culture - non-culture are connected areas that need each other. Culture does not live in the contrast of the internal and external only, but also in the transition from one into the other - it fights with chaos but also creates it.

When closed space (internal) is built, the open one (external) also leaks in there. Therefore culture is built up as a hierarchy of semiotic systems and as a multilayered arrangement of extra-cultural sphere. The type of culture is determined by the internal structure, i.e. the association and connectedness of semiotic subsystems (Ivanov & Lotman et alii 1998: 61-65).Death culture is the sum of different death-related conceptions and behaviours. Death is individual in the sense that an individual's conception of death and death-related behaviour does not follow the acquired and official religion, but is the sum of what has been read in books and experienced in one's own life. In the treatment of death we face the questions about life, death and postmortal life, because without life there would not be death either. (Pentikäinen 1990: 7-8)

Death culture can be analysed in its change, following how the new phenomena of life preclude earlier customs and precondition new phenomena of death culture (for example cremation). Consequently, despite the fact that death culture is a continuous process, substantial changes can be discerned in it, allowing us to identify periods of death culture. One of the bases of the periodical division of the 20th century Estonian death culture is the connection of the religion with images of death.

The central feature of the death culture of village community was its relation with religious outlook. In urban community this link has become weaker or disappeared at all. Death culture in the context of Estonian folk religion therefore involves death-related beliefs and customs, those unwritten social contracts between the dead and the living.

For the purposes of this article the definition of death culture could be the following:

Death culture is a synthesis of death-related beliefs and ways of behaviour, grounded on social agreements, or in other words, a system of death-related agreements, which among others is also expressed in beliefs and customs.

Earlier studies of death culture

There have been numerous studies of death beliefs throughout the history. In other countries in the world there was a turn in the treatment of the subject of death in the 1960s-1980s, in Estonia this subject remained in shadow because folkloristics concentrated on literature and the subject of death was not approved of by the dominant ideology in the society that denied death. After the silent years, in 1990, after Estonia had regained independence, active treatment of the subject of death started in folkloristics. There were several reasons: the gap in the earlier studies that needed to be filled; the topicality, universality of the subject, etc. Nearly all Estonian folklorists have dealt with particular topics of the subject of death, for example Mall Hiiemäe (the time of souls), Mare Kõiva (spells), Marju Kõivupuu (crosses), Ingrid Rüütel (the funeral customs of Kihnu), Kristi Salve and Vaike Sarv (lamentation), Ülo Tedre (funeral customs), Ülo Valk (the devil), Eha Viluoja (revenants and ghosts), etc. This long list of researchers gives evidence of the multilayeredness, prominence and, of course, the importance of the subject.

There is no general survey of the subject of death in Estonian folk religion. The earliest sources that include information on the Estonian death-related beliefs and customs are scattered in various printed matters. These were the 13th-16th century chronicles in German or Latin, 17th century court records, scientific narratives of travels, and descriptions of customs, mainly in German, from the 16th-19th centuries. As a rule these were written by non-Estonians, whose attitude to the local folk belief or customs was either interested or had a disparaging undertone. The beliefs were in active use at that time. The first descriptions of Estonian customs of death in the Estonian language date back to the second half of the 19th century. In the first half of the 20th century already important monographs by Estonian researchers M. J. Eisen, O. Loorits, later also by I. Paulson, U. Masing, e.a. were published. The author herself has been most influenced by and got theoretical bases from the works of Estonian researchers O. Loorits and I. Paulson, Finnish researchers Juha Pentikäinen, Lauri Honko, Veikko Anttonen and the French historian Philippe Ariés.

Attitudes to death and the dead

It is natural that over the years the attitude to the dead has changed in Estonian folk religion. One of the constant features is undoubtedly the fear of the dead. The dead is not a person any more, he is occupied by strange, hostile forces, his body is not functioning, vitality has reduced or disappeared at all, but he may still appear in dreams, which caused the conclusion that he is still alive, although in a completely different form of existence (Masing 1995: 78; Kulmar 1992: 1614). The cult of ancestors is typical of many religious systems. According to the Estonian researchers of religion, Matthias Johann Eisen (1857-1934) and Uku Masing (1909-1985), in Finno-Ugric mentality the communication of the living and the dead played an important role and the better the relationship was, the better the living were doing. The dead were feared, but it does not mean that the dead would have been entirely evil. The dead could have been good to one person, bad to another, depending on how the dead person was respected and if sacrifices were brought to him (Eisen 1995: 25-26; Masing 1995: 103.). They were treated not as friends but as creatures, who could not be taken into account (Masing 1995: 112). Today the dead is rather feared as something unnatural and strange. The commemoration of the dead on All Souls' Day, which is connected with the cult of ancestors, is more about burning candles and remembering the dead than a religious rite.

Faith in destiny has been characteristic of Estonians and other Finno-Ugric nations through centuries. From this angle the person himself cannot determine happiness, failure, goodness and evilness. This is also true today, as conversations with informants prove. Really, they do not call it fate that controls life according to belief, but some higher force, and their justification is that one has to believe in something. The length of life and the moment of death are predestined for each person. After the wreck of the ferryboat Estonia (1994) numerous interviews with the ones who had escaped were published in newspapers. The predominant idea in them was that in cold water what had helped them survive was faith that life could not end so soon and so pointlessly if it was meant to be much longer.

According to Estonian folk belief there was no definite border between the living and the dead. The here and there existed side by side. There was a chance of communication between the two sides. There may be two reasons why the influences between the living and dead were regarded possible: the natural view of the world saw the connection between the living and the dead, and there was the Oriental idea of rebirth. One pole of the communication between the living and the dead was the homecoming of ancestors during the time of the souls. The other was visiting one's ancestors' graves. It was believed that the dead person knew what state the grave was in and how he/she was mourned. The visits on the all souls' day have declined into visiting one's family members' graves, burning candles, and bringing flowers and kindly remembering the persons. These are the traces of old sacrificial customs, which aimed to conciliate death by means of sacrifices. The former animal sacrifice has changed into a symbol: a flower, a branch of a firtree, etc. The form of expression has changed over the years but the idea has remained the same.

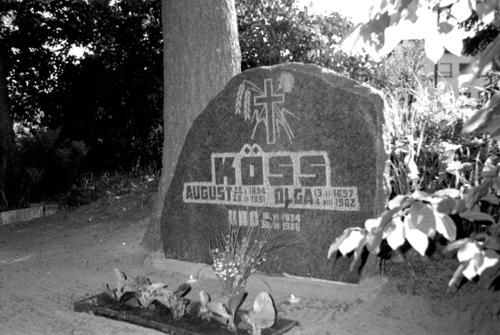

Modern features of offering customs. Photo: author's private collection 1998. To this day is valid the prohibition to take something from the graveyard, it could and can be related to ethical considerations. On the one hand people tried to avoid any contacts with the dead, on the other hand they made sacrifices to keep good relationships. Even today it is believed that one must not take anything with him from places that are associated with the dead. So picking flowers in the cemetery is not allowed, etc. There is a warning example about it from Southern Estonia (TK II 12 < Tartu town, Viru-Jaagupi parish): picking flowers from a cemetery ended with a car accident in which the picker was killed. The tradition of cemetery Sundays has been added to death culture. Such service days are meant to commemorate the dead but they include an underlying signal that graves have to be put in order by that time. Otherwise it would seem as if we did not care about our close ones.

Premonitions of death today

The general belief that death will come at a predestined time is significant in Estonian premonitions of death. It has also determined the function of Estonians death omens: people try to anticipate what is waiting for them and only after the person is dead, they try to prevent the next death by avoiding contacts or reconciling with the dead. People wanted to be ready for death for both ethical and economic reasons. It was believed that before each case of death ghosts give a signal. By means of observation people tried to look for signs that would give evidence of the destiny of the sick person. The answers were sought from experience and religion. There are many popular beliefs in the premonitions of death. Primarily from everyday life people expected to get an answer to the question how long they were destined to live. Seasons of the year, weather, the behaviour of farm animals and poultry, etc. were associated with premonitions of death.

In the interviews made in the 1990s many premonitions were mentioned, and this allows us to conclude that premonitions of death are topical also today. The internationally known premonitions like knocking and strange rumble have a wider spreading area.

2 years ago [1988] my sister Salme's son was drowned while swimming in the river near Moscow. We learned about it later. But that night when my nephew was drowned, there was a loud knock on our window. It was a beautiful quiet June night. I got up and went to the garden to see who had knocked. It was a beautiful quiet summer night. Not a dog was barking nor a leaf moving on the tree, there was no one around. And Kalle's spirit gave notice that he had died. Knocking always means death. (TK 1990, 1-3 < Viru-Jaagupi parish)

One informant has even added that such an omen had twice come true quite soon (TK 1990, 1 < Viru-Jaagupi parish).

At the end of 2000 Estonians were shaken by the death of a young woman after being gnawed by dogs. The woman's mother told the press of strange premonitions she had been followed by for half a year before the tragic incident:

In the summer already the floors of both my room and Marje's started to crack strangely, crack-crack and crack-crack. As if the floor was sinking.

She remembers her daughter's hairdryer having started on its own a day before the accident. Also a strange thump on the first floor, wide open doors and lamps in the ceiling that lit up themselves, the smell of fir in the room, etc. (Jakobson 2000).

Today also the ring of the doorbell or telephone has a meaning. If it is answered, there is nobody there (TK 1998, 2 < Tartu town, Rakvere town). The rattle of table foretells death in Setumaa even today (Vassiljeva 1996: 227).

Beside other signs Estonians have looked for weather forecasts and death omens from dreams. Interestingly, these are closely connected. Nearly literally, by seeing weather conditions death was predicted and by seeing the dead, weather was predicted. Through his existence man sensed his link with nature and therefore omens were looked for in nature - predictions of weather as well as of death. For the inhabitants of islands these two are identical. Bad weather could become fatal for people who are connected with the sea (TK 1993, 5 < Saaremaa island, Hiiumaa island).

While the deceased could appear to the living in dreams, it gave rise to the opinion that the person was continuing his course of life, only in another form and in another world.

Many a death omen is related to the sleeping of a sick person. The state of death is often identified with sleeping in religion. In both cases the soul leaves the body. The author is of the opinion that the explanations of several death-related dreams arise from personal experience: the person dreamed of something in his sleep and after that a crucial event happened, a case of death that later gave that dream a prophetic meaning.

I personally tend to believe in premonitions. It is so because of a dream or a revelation I experienced at the age of 5. I clearly saw that my dear uncle went across the footbridge to the other side of the river into a small house, and he never came out of it. Quite soon my uncle died. My parents were very much surprised that a child had foreseen death. (TK 1990, 1 < Viru-Jaagupi parish)

People link what they see in a dream with reality - if someone goes to a place, from which he does not come out, there will be death.

The behaviour of animals and birds has been meaningful for people for centuries. The majority of European peoples know the calling of a cuckoo as a premonition of death. In addition to the cuckoo, if a bird flies into the room, it will mean death (TK 1998, 1 < Tartu town). This omen, which has an international background, is widespread on the coast of Virumaa. Car drivers do not like birds to fly in the windows - it means misfortune (TK 2000, 2 < Tartu town).

The course of life of sick people has been predicted. For example the summer of 1998 brought about many unexpected cases of death, which according to doctors were caused by extraordinarily heavy air (TK 1998,1 < Tartu town). In autumn and in spring the air is humid and heavy, according to general observations it is a physically hard period especially for the sick. It is believed that long-time patients die in spring when trees are leafing or in autumn when leaves fall (TK 1990, 4).

It was thought that the temporary recovery of a patient, when he becomes interested in household and work, only postpones death for a short period. Before a crisis, long-time patients sometimes undergo a state of euphoria; so say doctors today, too (TK 1995, 13 < Rakvere town). The sensing of premonitons of death has been explained by the patient's and his closest people's condition of psychic stress, which is said to cause them to experience various phenomena of sound and light (Mikkor 1996: 168). Ivar Paulson calls such a condition "an expectative receptiveness" (Paulson 1966: 169). The change in the appearance of the patient is expressed by sensing the closeness of death.

A sick old person suddenly became hale. She started to put her house in order. The work progressed well. As if some inner force had helped her. Completed her chores and died in the morning. For a long time there were stories about the magic power that had helped her. It must be a singular feeling that gives strength. [---] People feel everything in advance. Only they do not know what exactly is coming. It is like an inner voice or feeling… nobody knows what the person who is about to leave this world feels. Usually recovery and continuation of life is hoped for. (TK 1990, 1 < Viru-Jaagupi parish)

A long road symbolises the way to the world of the dead. Today it is also believed that speaking of a road means death (TK 1990, 1-4 < Rakvere town). As well as this, today's observations refer to the feebleness of the dying person: a seriously ill person does not wish to be asked too many questions (TK 1995, 13 < Viru-Jaagupi parish).

On the face of the patient the so-called deadly pallor is distinguished as a prediction of imminent death. A usual premonition these days, the medics say (TK 1995, 13 < Rakvere town).

The sign that the patient is somehow not satisfied with his bed and demands another is one of the most widespread features of forthcoming death. This premonition is also believed in the 1990s (TK 1990, 10 > Viru-Jaagupi parish). Some patients want to go outside before death, to see everything there for the last time, remember and make sure that everything is all right. It is a symbolic farewell.

According to one informant it was very hard for her relative a few years ago to die in hospital because she had not been prepared for death, but had come to hospital for some time to get help. All works and activities remained unfinished, unarranged, without saying good-bye (TK 1996, 10 < Tartu town).

When the dying person asked for some specific food, death was said to be near. Also from the 1990s there are reports that the dying person asks for something good, for example bilberry dessert (TK 1996, 10 < Tartu town).

In general premonitions of death are expressed short personal narratives, descriptions of supernatural cases that the narrator himself or somebody of his close ones has experienced. These are interpreted as premonitions in retrospective mostly. Experienced observations and religious images are closely joined here. Such experiences are not easily talked about to a collector of folklore (or a stranger) (How can you say that I am probably going to die, I saw this and that …) or if they are, they are not considered serious premonitions of death. Obviously Soviet ideology has influenced this attitude - man lives forever and must be saved at any cost, although medicine may state the opposite. At the same time researchers of family tradition have noticed that conversations about death are stress-relaxing by nature - it had to go this way, somebody else has survived a similar case. Psychologically it is difficult to endure contacts with symbols that are associated with death, especially if someone among your own kin is on the verge of death. According to an informant she became angry when she saw quite a provocative woman in black, with a black hat and veil in the street, because her sister was in fatal condition in hospital at that time. It seemed like an omen of death. Later seeing the woman in the same outfit, she was not irritated any more (TK 2000, 2 < Tartu town).

Today it is regarded as unappropriate to watch the sick person to see if he is getting better or not. Premonitions of death are reflexive these days, they are believed to predict the death of someone else, usually a close person. So the tendency of premonitions is outwards. In the rational world of today the world of beliefs is more hidden - it is not appropriate to believe, therefore many problems are not discussed.

Funeral customs and changes in them today

Life is not pictured as an arc of life only. It can be figured in cycles: birth - death - birth. The life of a person must be organised by social agreements. If the person is standing on the border - after the moment of death and before the transition rites that confirm the crossing of the border to the other world - no extreme behaviour is allowed. One of the ways of concluding these agreements is funerals, in which the central part is played by transition rites. A person cannot remain on the border of two existences. He must be helped over the line to guarantee peace of mind. How it is done, depends on culture. In Estonian further information on this subject is available in the articles of Georg Elwert (1994) and Aivar Jürgenson (1998): Elwert and Jürgenson not only compare different cultures but also analyse the options and causes of different cultures.

Funerals were extended family events in the rural community. Speaking of Estonian funeral customs the cyclic nature has to be considered again like in the customs related to all the turning points of life (birth, marriage, death). These have a definite beginning, sequence of customs and end.

The formation of funeral customs in Estonian folk belief was the result of the understanding of death as a turning point in life, as the passage of a person from one form of existence into another. Even in their modern form the funeral customs of many nationalities are complicated and multifaceted, containing various components: customs, lamentation, beliefs, taboos, etc. This is complemented and significantly influenced by the psychological state of people - worry, sympathy, shock, stupor, perception of eternal separation (Sysov 1995: 395).

The author shares the thoughts of Aili Nenola the conceptualisation of death-related rituals. According to her the death-related rituals cannot be defined by the funeral rituals only. These actually cover all the stages of the process of death: physical death, disposal of the corpse, social death. In this connection three kinds of death rituals can be discerned: death, funeral and commemoration rituals. All the three together form the norms of conciliation with death, by means of which the mourners can express their feelings publicly, and the people around them accept it (Helve 1987: 45-46). While in rural community all the rituals were important, today the death rituals are left aside. Why? People often die in hospital, not among his close ones. The deceased is often seen only on the funeral day.

People who have had contacts with death even now find that the patient must be let die in peace, if it is seen that there is no hope (EE 515: 166), not to lengthen his suffering with the help of medicine. Old people want to die at home these days too, not in hospital surrounded by strangers (Arpo 1996: 250). All over Estonia it was believed that the last wish of a dying person is sacred and if it is not fulfilled, it will bring misfortune to those remaining. The same belief is also in force today (TK 1998, 3 < Rakvere town, Tartu town). For example in Western Estonia there is an unwritten law that there are taboos related to the dead that you cannot break, otherwise you will call death on yourself (TK 1998, 1 < Risti village).

With the development of commercial relations at the end of the 19th century, manufactured clothes were more and more used as graveclothes. Even if these were homemade, old beliefs (there must not be any knots, etc.) were not followed any more. In the 20th century people choose their graveclothes themselves. The accepted colour for old people is black, old women have a scarf, men are buried bareheaded. Depending on the wish of the dead person, he/she may wear shoes. New requirements are connected with cremation; for instance all the details of the clothes must be combustible.

Even today people know the custom that at the front door of the house of the dead firs with broken tops are placed and the path from the house is covered with fir branches. Yet they cannot explain it any more what the religious background of this custom is. They are today the passive carriers of the tradition. It becomes topical for them only in certain critical stages of life, and they do not ponder why, but how.

There were strict rules about funerals, which are also considered today: the son must not dig his father's grave nor carry his coffin (TK 1998, 2 < Rakvere town).

Even in the second half of the 20th century lamentation for the dead is familiar in Setumaa, this is combined with the regilaul folk song tradition and results from the lamentation tradition. The treatment of Setu lamentation culture focuses mainly on the lamentation and the tradition as communication, which arose from the relations of an individual and the group, was historically formed in the definite environment and was used in a community relatively closed to external influences (Sarv 2000: 41-43). Lamentation often speaks how the old person, the dead, was treated. If there had been negative incidents, it was like a public ignominy at the funeral (Järvinen 1996: 6).

Speeches are given in memory of the deceased. This is a retrospect of the life of the dead. Estonian funeral culture includes an ethical norm not to speak badly of the dead (in such case it is better not to speak at all). If due to some reason the deceased person will not leave the living alone, by appearing to them in dreams, disturbing the living, there are people even today who can recommend how to get rid of such haunting relationship. For example, a woman from Kihnu island, born in 1926, describes how she was taught to go to the grave of the dead and read the Lord's prayer and that it really helped (EE 515: 9-10).

In Setumaa it is believed that the spirit of the dead is on the earth for 40 days. It goes around and reveals itself to people and sometimes talks to them. Even today the Setu people associate the word 'commemoration' not only with remembering the dead person but also with the activities that are beneficial for the soul of the dead in the other world (hengemälehtüs). During 40 days in the house of the dead some food, a cup with water and a scarf or some other sign is kept for the soul. Some people associate it with the commemoration of the deceased, but a large part also remembers the initial idea of the custom - these items were for the homecoming spirit to eat and wash. Even the custom of deathwatch is usually explained by honouring the memory of the dead. Many confess that they cannot watch all night, the relatives just go and see him. This is already an attitudinal change in the conservative customs. The situation of the soul can also be relieved by sincere prayers by the family. The food that is taken to the grave and church is said to be for the soul, but still more speak of the custom of commemoration (see Vassiljeva 1996: 221-222).

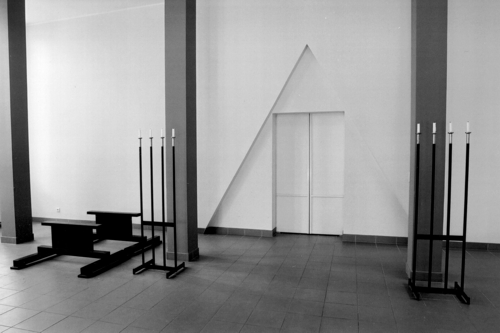

Traditionally those turning points of life, in which a person passes from one state to another, are connected with rituals. These passages are connected with fear, regarding both the individual and the society. Just the fear and the risk cause rituals, by means of which these situations are made sacral. A ritual observance is always communication within the community. The prerequisite of an operating communication is that the participants should acknowledge the respective symbols and signs in the same way. For example, in Tartu Crematorium the image of a gate is used - the dead person is taken through the doorway - it is symbolically crossing the border, leaving this world.

A person, who is already dying, figuratively steps over the threshold - strictly speaking, he is not here any more, but he has not gone anywhere else yet either. Such a person is not a so-called usual person any more, and attitude to him is different.

Symbolically crossing the border: the gate of a cemetery and the threshold of a crematorium. Photos: E. Selleke; A. Tennus.

Change in death culture

There are different medical, legal, theological definitions of death. These are mutually related, following universal ethical principles. A person's life is legally protected. The life of a person can be pictured as an axis, on which the leftmost point marks the beginning of life and the rightmost point - the death. All in between is life. The development of biology and medicine today has taken us to the truth that these end-positions cannot be marked by a point or a definite limit any more. It is legally known that the dimensions of life may extend over the border of death, for example, the slander of a dead person is punishable by criminal law. Also the criminal law of many countries protects the 'peace of the dead', our criminal code more restrictedly, "the memory of the buried" (KrK § 199) (Sootak 1996: 1814).

The violation of the memory of the buried is firmly condemned from the point of folk belief. There are several beliefs, which warn against violating these ethical norms. Beside the one that nothing can be taken, let alone steal (e.g. flowers, wreaths, grave lanterns, etc.) from the graveyard or break anything there, the dead person himself is a taboo - his peace must not be disturbed. Even these days in Virumaa several stories are told as a warning, of vandalism in the cemetery, as a result of which (it is believed!) the culprit was punished with death (TK 1998, 3 < Rakvere town). Today grave robbing and vandalism in cemeteries is not exceptional. Later it often comes out that these acts have been performed by schoolboys, who in their own words do it because of fun or boredom, to show their courage or being induced by satanism. One of the reasons for such vandalism these days is divergence from death. Death is as anonymous as the dead. Children are not taken along to funerals. Partly artificial distance is kept with death. If the same grave robbers had experienced the death and funeral of close people, if they had seen their parent's or good friend's body buried in the ground, they would hardly have got the idea of trampling in the cemetery. It is unlikely that the schoolchildren of Pala or Kuressaare would damage their local graveyard where their perished schoolmates are buried (in Saaremaa two schoolchildren were killed in the fire of Kuressaare Gymnasium in 1995; in Jõgevamaa 8 students of Pala Basic School were killed in a bus accident in 1996).

Ethic norms may not be violated - punishment will follow sooner or later. The best punisher is one's own conscience. This is one of the norms of today's death culture.

Death has always been in people's thoughts, the notion has undergone its changes together with the development of human thought. In the social plan the death philosophy is significantly affected by the cataclysms that Europeans have had to survive during this century. The19th-century romantic model of beautiful death started to change already after World War I, when Europe saw millions of people die at the same time. According to Philippe Ariés this fact alone put "mourning under a silent ban" (Ariés 1992: 478). The works of several well-known authors, for example All Quiet on the Western Front by Erich Maria Remarque, agree with this context.

The psyche of Estonians has been influenced by World War II as well as the severe deportations to Siberia in 1941 and 1949 - in such cases there cannot be any justification to death. Heroic death can be in question only when talking about the War of Independence (1918-1920, to defend the independence of Estonia against Soviet Russia).

Jaan Sootak gives three reasons why death has become anonymous for the 20th-century Europeans and why they have been estranged from death:

- The enormous scope of death and destruction,

- The development of health care and medicine,

- The secularisation and rationalisation of people's daily life.

In the 20th century the self-aware person has started to talk of his right to death as a right of self-determination based on human dignity. The society has to secure the course of a person's life in conditions that would preclude violent or untimely death conditioned by other social circumstances. It is not death itself that is unnatural and awful, but the fact that people die of unnatural and awful death, not the way they would have liked to die (Sootak 1996, 1815-1817).

Dying is not a biological process only (see more Sootak 1996: 1821-1822). In the 1992 folklore field trip of the University of Tartu an 80-year-old informant from Hiiumaa answered the question, what she thought life was:

Dear child, there is nothing else about death than the human organism just stops existing and that is all. [Adding later:] Don't you read "Eesti Loodus" ['Estonian Nature', the journal)? (TK 1992, 1 < Hiiumaa island, Suuremõisa parish).

There is a risk for the hospital staff that in the 'easy' and quick death of a patient they may see a chance to release themselves from the burdening compassion and sympathy. Today it is said that already the doctor's glance and posture will betray a patient's fatal illness. Nothing else is needed (TK 1998, 3 < Tartu town).

There is a momentous change on the way in the world - the intercultural communication is becoming more and more usual. The interaction actually concerns all rituals today. Intercultural communication obviously drives people to learn about the value systems and traditions of other cultures. Particular attention would be paid to death culture. The spectrum of rituals and conceptions in it is extensive (Pentikäinen 1990: 193).

Marika Mikkor has shown in her studies that Estonians in Caucasia have done their best to retain their funeral traditions, but even there the influences of the death culture of the neighbouring Armenians, Georgians, etc. are evident. The funeral customs of the Russians, Ukranians, Byelorussians who live in Estonia are a symbiosis of different cultures. The foreigners who came to Estonia decades ago when young, did not have any funeral traditions characteristic to their nation to take along, some of them had never been to funeral in their lives. For example one second-generation Byelorussian immigrant in Ida-Virumaa described how they adjusted themselves to everyday life in their new location, but at the funeral they faced a serious question: how to do it. Death culture is too serious a subject so anyone would notice if his culture has been cut through. Yet they did not know the local customs well enough either. Nobody knew exactly how it should be done, how is correct. When the children who were born in Estonia went to visit their grandparents in Byelorussia, they were surprised by the clarity and order there - everyone knew how it should be done, everything was so logical (see Jaago 1996: 183). In such area and connections the role of older people in the society becomes evident.

Earlier death was rarely called by name, probably due to religious reasons. But even today circumlocution is used for death. In the obituaries in Estonian newspapers such periphrases can be seen as 'left this world', 'set out on his last journey', 'went to manala ['the underworld']', condolences are expressed in connection with the 'death' or 'loss' of someone.

The French social historian Philippe Ariés considers the attitudes of contemporary Europeans as "death-negating" - the generation of death negaters. According to him there are three reasons for that:

- The belief of the contemporary person in the infinite power of technology and the complete rule of the nature, and especially in medicine is so strong that death could be forgotten;

- Traditional forms of society have disappeared. People who have distanced from their usual environment and who are living in seclusion have no possibility of contacts with death in the same way they had earlier in their homes and villages;

- The problem of evil. Ariés remarks that in Europe the belief in the existence of evil was in the background until the 1700s, death was regarded beautiful like a Christian symbol. In the 20th century people are not able any more to romanticise death, it is disgusting and disagreeable for them. Therefore it is negated just like old age and diseases are (Pentikäinen 1990: 192).

The standpoints of Ariés are interesting also for estimating our death culture today. In a rural community the family, relatives and neighbours experienced the process of death together. Now, as requested by the family, death often occurs in the atmosphere of hospital. Dying at home is regarded as a kind of misfortune. What will you do with the deceased there? One will feel powerless, because he cannot help, but conciliation with death seems unnatural.

In developed countries death has acquired a passive role in the nursing wards of hospitals. Estonia is still on its way and hopefully the destination point is far away.

In the rural community death was public within a cultural group. In the case of death many social and emotional agreements and associations of the society arose, brought forward by the cognitive and intuitive symbols typical to oral tradition, like funeral clothes and definite customs. In today's urbanised society the relations of people in case of death have also changed. The death of public figures (for example the businessman Rein Kaarepere, music manager Margus Turu, actor Aare Laanemets, sports commentator Toomas Uba) becomes the focus of general attention (often drawn and directed by the media), which is further amplified by the tragedy of the death (for example the homicide of the actor Sulev Luik, the violent death of the athlete Valter Külvet or businessman Mait Metsamaa). Although the news about the number of perished in a plane crash or natural disaster is generally received with minimal perception of death, in certain cases such mass death can become the public pain spot of the society (the catastrophe of the ferry Estonia, the death of Estonian peacekeepers at a failed mission in Kurkse, the attack on the World Trade Center, etc). In the above cases the public does not always share the mourning. They rather discuss the predetereminedness of life and death on the basis of these examples. The 'leaving' of a common person is confirmed by the death certificate signed by a doctor or a clerk and an obituary in the newspaper that does not mean much for the general public. In both cases mourning is limited to a very narrow circle of people, mostly close relatives. For the wider public death remains out of the normal routine, and exists only as a fact on the paper. Today's death and the treatment of death could be described as follows: the goal is that a person should die in hospital, not at home. The leaving should take place among medical workers, not the closest people. Therefore the automatic routine of death is: hospital - preservation - autopsy - funeral agency - funeral - death certificate.

The family is painfully touched by death. The death of children and grownup working people is regarded unnatural. Yet it happens, mainly due to accidents, for instance car accidents. At the end of the 1990s roadside monuments to the victims of car accidents became a burning issue. According to Ago Gashkov, a TV reporter from Ida-Virumaa, and many others, these look like a roadside cemetery. The marking of the places where the crash victims were killed may be seen as a marginal phenomenon of death culture, which at closer observation carries in it the archaic belief of the connection between the soul and the place of death. The memorial stones definitely symbolise the risks of the contemporary civilisation. It is a kind of protest against the injustice of fate and the impotence of the society, which cannot protect its members. It is also a kind of warning that today nobody is secure from unexpected death (see Kõivupuu 2000). Another question is how other members of the society who do not know the one who was killed, relate to such reminders that they notice at the most unexpected moments.

The death, accidents and also suicides of children are interpreted differently from earlier times. Everyone regardless of the reasons of death is buried in the blessed earth. Obvious are the attempts of relatives to deny suicides and alcoholic deaths, which shows that these options are not considered decent. This in its turn is associated with the above-mentioned ethic norm that nothing bad is spoken about the dead.

Death is spoken of more openly if talking about the last journey of old people. It is partly natural, because death is connected with the so-called accepted age of dying. Today there are no specific types of oldsters. Different lifestyles are followed: who goes travelling, who looks after grandchildren, who tries to keep to the traditions of the beginning of the century, who waits for death… It seems that earlier grandparents had a role in looking after and teaching grandchildren, now this part is played by schools and kindergartens. The urbanisation process has given rise to new lifestyles. Life expectancy is longer; usually it is preferred not to live together with one's grandparents. Children leave their parents early.

In today's Estonian society both oldsters and children have been left in the background. Old people have to manage themselves or with the help of their children (relatives). Here arises their problem with death - old people in our developing society, where prices are rising and the living standard is low, cannot even cover their funeral costs. Many thinks that you cannot depend on children or grandchildren in this question - you have to have money to arrange your own funeral. The greatest worry of oldsters is not the fear of death or religious ignorance of the existence of the other world, but the pain to be completely dependent on other people (TK 1998, 3 < Rakvere town).

In the culture of developed countries old age depression, hypochondria and paranoic anger may be detected more frequently than wiseness. In some West-African cultures it is stereotypical of old people to talk about death, pretending sadness (Elwert 1994: 392-393). In Estonia old people also talk of death among each other (TK 1998, 3 < Rakvere town). In several countries already the so-called old age culture is developing: in America cities have been founded for that purpose. In other societies they may go to welfare centres or homes for the aged.

It is certain that in Estonia people go to the home for the aged only in extreme need and despair - this is a punishment and according to unwritten law - disgrace to the close relatives (especially children) that they have not found another solution. "Haven't I really worked enough in my life to have to end my days in a home for the aged…" (TK 1990, 3 < Rakvere town). Elwert offers the following to mitigate the situation: firstly jubilee albums, eulogies, compensations when the status changes; and secondly taking the major role in bringing up grandchildren (Elwert 1994: 398). The state should secure a certain quality of life and ideally the social policy should be arranged so that old people would perceive the support, but would not rely only on that.

In summary

The conceptualisation of death reflect people's attitude to life in different eras. The death-related beliefs are pervaded by fear and reverence of death. The first arises from unawareness and regarding the corpse as dangerous. According to folk belief unexpected death has been feared, not death itself - this was barely the continuation of life in the other world. You had to be ready for death. Reverence is based on the belief that dead ancestors influence the future of the living and involve magic force.

Why do we need death culture even today? In the state of high emotions people cannot find a way to express their feelings more easily. Here the funeral customs with their established practices and ethical norms are of assistance. Rituals help to create balance within people and arrange their relationships with the public. Death touches each and every person. The more we know about it, the more firmly we feel in this difficult situation. Funeral customs also serve as a form of securing consistency between generations.

Today's death culture operates on different levels, includes details from various times, beliefs, cultures. Integration processes are inevitable at funerals. This shows the intercultural relations in the specific region. In Estonia death-related traditions have not been interrupted. The old unified tradition with ancient rituals are being left aside, but under the surface traces of old folk customs can be detected in different regions. Death will become the monopoly of specialists in Estonia, too. This is connected with industrialisation, urbanisation, development of medicine. In rural areas traditions last longer (even now the deceased is placed into the coffin, funeral feast is held at home). Death culture has become more individual, but the changes are still so recent that they have not acquired a definite shape. Serious urbanisation in Estonia started only after World War II on account of the new immigrants from the republics of the Soviet Union. Therefore the tradition of urbanised society cannot be as powerful as in larger countries. Still it may be said that from the point of an individual in modern Estonian society death is the last event in the biography of a person.

Translated by Ann Kuslap

References:

EE = Eesti Elulood (Estonian Life Stories). The collection is availabe in the Estonian Cultural Historical Archives in the Estonian Literary Museum, Tartu, Estonia.

TK = The collection of Tiia Köss from 1990-2000. 1st part given to the Estonian Folklore Archives.

Ariés, Philippe 1992. Chelovek pered licom smerti. Moscow.

Arpo, Martin. 1996. Noppeid setu vanade matmiskommete kohta. - Palve, vanapatt ja pihlakas. Vanavaravedaja, nr. 4. Tartu, lk. 241-267.

EE 1990. Eesti Entsüklopeedia, nr. 5. Tallinn.

Eisen, Matthias Johann 1995. Eesti mütoloogia. Tallinn.

Elwert, Georg 1994. Vanadus eri kultuurides. - Akadeemia, nr 1, 2. Tartu, lk. 150-161; 386-403.

Helve, Helena (ed.) 1987. Ihmisenä maailmassa. Helsinki.

Honko, Lauri & Pentikäinen, Juha 1997. Kultuuriantropoloogia. Tallinn.

Ivanov, V. & Lotman, J. & Pjatigorskij, A & Toporov, V. & Uspenskij, B. 1998. Theses on the Semiotic Study of Cultures. Kultuurisemiootika teesid. Tartu Semiotics Library. 1 Tartu.

Jaago, Tiiu 1996. On Which Side of the Frontier Are Trespassers? About the Identity of Ethnic Groups in Kohtla-Järve. - Ülo Valk (ed.). Studies in Folklore and Popular Religion 1. Tartu, pp. 181-195.

Jakobson, Kadri 2000. Koerte ohvri tuhk puistatakse merre. - SL Õhtuleht. 28.12.2000.

Järvinen, Irma-Riitta 1996. Akal henk on ku kazil. - Aamun Koitto, nr. 12. Kuopio, s. 4-8.

Jürgenson, Aivar 1998. Tapetud laps ja lapsetapmine pärimuses sotsiokultuurilisel taustal. - Mäetagused nr. 8, lk. 28-57. http://haldjas.folklore.ee/tagused/nr8/lapsetap.htm.

Kulmar, Tarmo 1992. Eesti muinasusundi hingefenomenoloogiast. - Akadeemia, nr. 7-9. Tartu, lk. 1379-1393, 1601-1621, 1870-1888.

Kõivupuu, Marju 2000. Kalmistud teede ääres. - Kõiva, Mare (toim.). Meedia. Folkloor. Mütoloogia. Tänapäeva folkloorist. II. Tartu, lk. 285-323.

Köss, Tiia 1998. Surmakultuurist eesti rahvausundi põhjal. Magistritöö. Tartu. Master's Degree Thesis. Manuscript in the University of Tartu, Department of Folklore.

Loorits, Oskar 1990. Eesti rahvausundi maailmavaade. Tallinn.

Masing, Uku 1995. Eesti usund. Tartu.

Mikkor, Marika 1996. Linnud, loomad, ebaselge päritoluga hääled ja unenäod surmaennetena Kaukaasia eestlastel. - Eesti Rahva Muuseumi aastaraamat XLI. Tartu, lk. 167-181.

Paulson, Ivar 1966. Vana eesti rahvausk. Stockholm.

Pentikäinen, Juha 1990. Suomalaisen lähtö. Helsinki.

Sarv, Vaike 2000. Setu itkukultuur. Ars Musica Popularis, nr. 14. Tartu-Tampere.

Sootak, Jaan 1996. Surm kui kokkulepe. - Akadeemia, nr. 9. Tartu, lk. 1814-1839.

Sõsov, Vladimir 1995. Surnuitkud ja matusekombestiku psühhologismi dünaamika. - Mare Kõiva & Mall Hiiemäe (toim.). Rahvausund tänapäeval. Tartu, lk. 395-399.

Vassiljeva, Tea 1996. Üks patujutt. - Palve, vanapatt ja pihlakas. Vanavaravedaja, nr. 4, Tartu, lk.. 133-143.