The phenomenon of an athlete.

Georg Lurich from a historical figure to the hero of folk talesKalle Voolaid

The athlete Georg Lurich was a person who managed to imprint a deep mark in the memory of Estonians. Although he was active more than a hundred years ago, he now and again emerges as a hero, when someone somewhere talks about the national pride and dignity of Estonians. Tales are spoken about Lurich, he has become a myth. Why? The most provocative question is - why has Lurich left such a deep trace and how measurable is that trace? Is there anybody anywhere who could excite people to a similar degree? Much of what Lurich has done lives only in myths and is still waiting for a more thorough (further) research.

Historical background

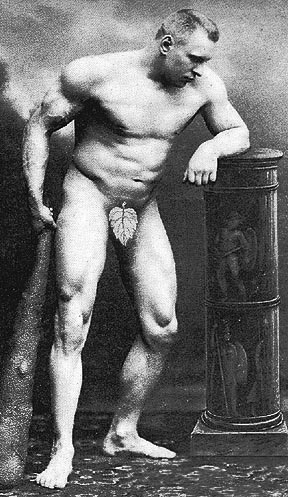

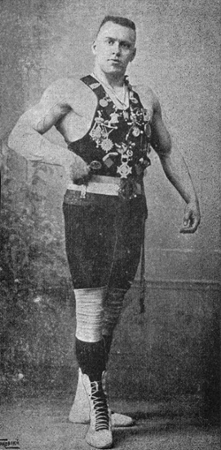

Lurich had a most harmoniously built body and was therefore used as a model by several famous sculptors. Estonian Sports Museum. Modern sports started to develop in the first half of the 19th century in Great Britain. At that time the territory of Estonia was culturally in the German sphere of influence. The same phenomenon was also discernible in the sports life here - when the more active sportsmen started to become organised in the middle of the 19th century, the Baltic Germans were among the initiators. The first athletic associations that were founded in Estonia in the 1860s were the Baltic German gymnastic associations in Tallinn and Tartu.

Estonian sports enthusiasts took the first steps in organising in the last decades of the 19th century. The first (unofficial) Estonian athletic association was the Tallinn heavy athletics club formed by the heavy athletics enthusiast Gustav Boesberg in 1888 (Hallismaa 1998: 28). From the heavyweight lifters and wrestlers who practised in that association the first great generation of Estonian athletes arose. One of the best known among them was the later national pride and honour of Estonians, the versatile professional athlete Georg Lurich.

The second half of the 19th century was an extremely important time for Estonians - it was the time of awakening, of national self-awareness. The main attention was paid to the self-determination in general - the discovering of definite means of self-expression (including sports) was only beginning. The development was hampered by several problems - the clubs were in their initial stage, the euphoria of finding one's identity was hit by Russianisation, etc.

It was the time when each success of fellow countrymen was welcome and a national hero was a hero indeed. It can be said that Lurich happened to be in the right place and in right time. He was by no means the first Estonian athlete, nor the man, who introduced heavy athletics in Estonia, yet he was the most popular athlete in his time. His role in the popularisation of sport in Estonia was really remarkable. Unfortunately it is quite difficult to get a factual overview of Lurich's sportsmanship. Although it is generally believed that Lurich was successful as a sportsman, the documentation of his achievements is problematic. Obviously partly because at that time both the statistics and archives of sports as well as the regulation of sports life in general were still in its infancy and there was no system of contests for professionals or breaking records (Langsepp 1996: 30). But evidently Lurich became a hero partly also because he himself wanted to be one. It seems that he was a man who well understood what advertising means and who, playing according to these rules, skilfully raised his own popularity. Often he was so skilful that even later many have accused him of having cheated. In some cases it is really likely - for example the story of Lurich's victory over the world champion in free-style wrestling, the American Frank Gotchi in the 1913 match, which actually may not have taken place at all, as Voldemar Veedam has written in his book Lurich Ameerikas (Lurich in America) (Veedam 1981: 85).

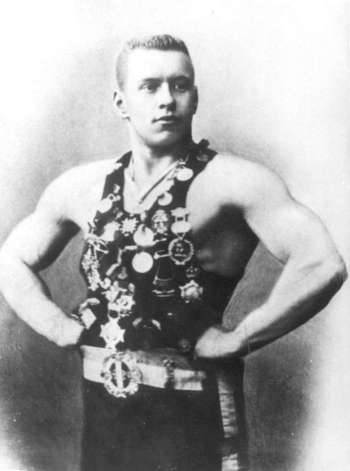

So it may be said that according to 'undocumented information', Lurich was the winner of world and European championships in professional classical wrestling, also he is said to have broken many world records in different styles of weight-lifting. Enthused over the activities of the athlete, sports associations and clubs with his name were founded all over the world. Lurich had a number of imitators who used his name for advertising themselves - the so-called 'false Lurichs' (Kristjanson 1973: 125). The farthest 'false Lurich' was in Australia, in a place which Lurich himself never visited (Vilder 1996: 107). Lurich was a great innovator of wrestling; he introduced tens of new wrestling techniques (Sepp 1984: 2) and designed a training system suitable for himself.

Mirror images of the hero as different viewpoints of reality

There are tales about Georg Lurich, which have moved around among people for a hundred years already - I found first of them mentioned in the Postimees no. 279 of the year 1898, the last to this day was written down in May 1996: a total of approximately a hundred stories. A number of the tales can be found in the ERA and RKM folklore collections in the Estonian Literary Museum, but not all of them. The tales are collected from literature and periodicals; I have also collected them myself.

What kind of image does Lurich have in folk tales? The following analysis is inspired by an article by Priit Pirsko Talud päriseks. Protsessi algus müüjate ja ostjate pilgu läbi (Farms forever. The beginning of the process from the point of view of sellers and buyers) (Pirsko 1995), in which for describing one and the same procedure - the bought and sales of a farm - he uses different sources: newspapers and folk tales in German and Estonian, in order to disclose the transaction from many different aspects. Pirsko says:

The press may be observed as the mirror of the society, which focuses its attention on one or another phenomenon, as required. In a figurative sense we may state that if the mirror is inclined, the public opinion will also be inclined. (Pirsko 1995: 106)

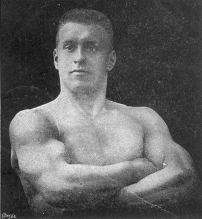

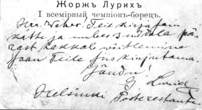

A postcard with the autograph of Lurich (1903). Estonian Sports Museum. The press, a mighty medium even in those past days, also shaped the charismatic image of Lurich during his lifetime and after his death. People who have met Lurich create their own image of him, folk tales picture the athlete as a positive hero.

Georg Lurich was a real historical person. Therefore there is the question to what extent the folk-tale-Lurich corresponds to the real historical individual. Tiiu and Kalev Jaago have studied the proportion of reality and narrative truth in family narratives, especially in stories about the origin of one's ancestors. The study reveals that there are factual errors in the narratives that are believed: for example, a Swedish ancestor turns out to be an Estonian (Jaago & Jaago 1996: 64-127). The situation about Lurich, however, differs from family narratives: if the narrative truth of a story concerning one's ancestors can be checked with the help of archive materials, in the case of Lurich unfortunately it is in most cases impossible to find out which activity or event serves as a basis for such tales. Yet it is possible to discriminate the reflection of a folk tale and in this way draw conclusions about the historical Lurich.

In the analysis of the folk tales I have proceeded from the treatments explaining the proportions of reality and the narrative by Vladimir Propp and Mall Hiiemäe.

Vladimir Propp (1976: 115) produces the link of folklore and reality in three theses.

1. Folklore, like any other category of art, stems from reality. Even the most fantastic images in folklore are based on reality.

Lurich was a historical figure. Hearing-experiencing a folk tale with Lurich as a hero, the question arises: is it a true story, is it based on something real (event that actually happened)? It is certain about most tales about Lurich that they do not reflect actual events. What do they reflect then? Why do they exist?

2. Despite the will of the creators and narrators of folklore, it expresses real life. The forms of expression and their contents are different depending on the genre.

The narrator does not lie deliberately, even if the pattern of Lurich does not agree with real life. He (the narrator) rests upon another truth, another reality - folk tradition.

3. The narrator sets an aim to reflect reality taking its requirements into consideration.

The narrator tells stories with a certain aim (to entertain, for example) and this will determine the narrative truth. Tales about Lurich are linked with reality through Lurich as a historical person, partly also through the motifs of the story and its traditional style.

Mall Hiiemäe (1978) has dealt with analogous material in her treatment of Kodavere narratives. The stories she has studied are local, differently from the tales handled here, but the stages of folklorisation of a tradition based on facts, provide a good parallel to our topic.

About narratives of local origin it is normal that the users of the narrative (i.e. both narrator and listener) know the certain people, the prototypes of the story, they know the events that make up the plot of the narrative, and the conditions that the story is about. Briefly - these narratives are based on the specific with regard to the users. Tales that reflect real life facts the specific knowledge of which has got lost do not belong here: many funny stories may transfer such facts but the original link with the specific has been lost, as the story has spread.

Depending if the folk tales are based on knowledge about the specific or the major part of their contents consists of a traditional plot, the tales can be dealt with in groups, in which the proportion of the specific gradually decreases and the proportion of the traditional increases. (Hiiemäe 1978: 38)

Stories about Georg Lurich also point out his central quality (great strength) and his name, which maintain or at least refer to specificity.

According to the above, Mall Hiiemäe divides the narratives into thee groups. The more the narrative is detached from real life as its fundamental fact, and is grounded on earlier narratives, the more folkloristic it becomes:

The 1st group starts from the borderland of the description and the narrative, the contents of the stories of this group are mostly based on the knowledge of the specific. The narratives of the 2nd group also include the motifs or even whole plots of folk tales, but the part of local origin is predominating. The narratives of the 2nd group use more structural elements of folk tales than those of the 1st group. The borderland of the 2nd and 3rd group is marked separately. Here belong stories in which the proportion of the specific and the traditional matter is more or less equal. The 3rd group consists of narrative forms with plots known in wider tradition, and they either involve the local matter to some extent or not at all. (Hiiemäe 1978: 39)

In the following a principally similar classification is employed, although a relatively small group of people sense the specificity connected with the local narrative tradition and the figures of the family narrative. Tales of Lurich as a historical and well-known person are more widely spread.

Tales about Lurich

Georg Lurich (22.04.1876 Väike-Maarja - 22.01.1920 Armavir). Estonian Sports Museum. Tales about Lurich can be classified into three groups - from the stories of each group we get a different reflection of Lurich:

1. the first group is made up of stories about Lurich as a real historical person and about his relationships with his students and other wrestlers. The majority of these stories are most likely collected from wrestlers who knew Lurich directly. As these stories are too much based on specific facts, they are relatively less folkloristic and at the same time, most believable;

2. the second group, the so-called transition group, consists of narratives, the main character of which - the real historical Lurich has acquired new traits of the general narrative tradition. It seems that here the narrator does not ask if it is true or not. He creates an illusion of reality, of something that could really have happened;

3. to the third group belong stories about Lurich as a traditional athlete - a hero whose actions have no connection with the historical Lurich. This is the most folkloristic part of tales about Lurich, they are the furthest from the historical Lurich and are most of all connected with traditional stories about the man of muscle. In the case of this material it is doubtful to what extent it was believed, evidently its function was different. Lurich himself is not important, he is an image, which expresses some other idea (the function of a defender, deus ex machina).

It is worth mentioning that most of the stories of the first and second group were collected by Tõnu Võimula, a wrestling enthusiast and collector of folklore who knew Lurich personally, in the course of a special campaign in the 1930s. (1) Võimula namely planned to compile the biography of Lurich, which never has been published though.

Tales about Lurich as a real historical person

These stories mainly talk about Lurich's relationships with his students and other wrestlers, also simply about his performances-competitions. Võimula collected most of these stories, in the greater part from former wrestlers who knew Lurich themselves or people who had witnessed Lurich in action.

These are mostly tales with a humorous undertone, narrating about tricks played by Lurich. Examples:

When athlete Aruküla went to St. Petersburg to join G. Lurich's group, he came to the old Riga hotel in Uus Street, where Lurich lodged. At that time there were even more Estonian athletes who were spending their time at a glass of beer, having a talk and they had already emptied some bottles. Lurich commanded athlete Erdmann to ring the bell and order some more bottles. Erdmann pushed the button in the doorjamb. Soon the waiter came and brought what was ordered. When they had drunk it, Lurich told Aruküla: "Ring for some more beers!" Aruküla went to the door, pushed against the doorjamb, but to no avail. Lurich said: "Ring again, but push harder." Aruküla pushed as hard as he could but the waiter did not come. Then Lurich said: "You do not have any strength. See, when I ring, the waiter comes at once." Saying so, he pushed against the doorjamb and the waiter appeared at once. Aruküla had not noticed the button, he thought you had to push the doorjamb. (2)

There were important wrestling competitions in Riga in which Lurich participated. After wrestling they went to a nice club to have dinner. Their suddenly one pretty girl came and asked to join them at their table, and she was allowed to. Conversation flowed smoothly, Lurich had been especially joyful. Suddenly he had broken wind, but did not cease to talk. Aberg, Kalde and others tried hard to keep from laughing. Soon quite a strong farting followed and now the others could not suppress laughter any longer. Now the girl swept away from the table. Then Lurich explained that she was not a usual prostitute, but an expensive bait who drove men mad in order to cheat them out of money. (3)

When Lurich gave athletic performances in Viljandi, he had had quite good income there - the hall had been crowded every night and all tickets had been sold out to the very last. Before the last night Lurich had announced on the wall posters that each of the audience would get a picture of him as a present. That night there were even more people, each had wished to get the allowed picture. When the program was over, Lurich had come to the stage and put his hands on hips and said that this was the picture, the most perfect picture of him. People had not been satisfied with such a picture, they had demanded that they were allowed a picture to take away with them. When people have started to demand their money back, Lurich had said that they would get a picture in the size of a post stamp and the one who gets to the box office first would get a large picture. Then people had started to pour out and the fastest had got a large picture. But the police had made a report, it is not known what its result was. (4)

Lurich is drawn here as a humorous, jolly person who also likes to take part in his tricks. He does his main job - wrestling - with maximum attention and requires similar dedication from others. Relationships with the opposite sex cause some problems for him; Lurich is cautious about his female fans and tries to eliminate their approaches from the very beginning.

Tales of the transition group

In the tales of this group Lurich has slightly changed in comparison with the Lurich of the previous group. The tales are more varied in subject matter; there are variations in the behaviour of the hero, in his companions and locations.

When Lurich's mother had been pregnant, she had gone through the wood and happened to see a bear there, which had frightened her. The result of the frightening was that she gave birth to a son with bear's strength, because the bear's strength had gone into her son. (5)

One hot and sunny summer day Lurich had been sitting on a hill slope in Väike-Maarja and when the heat was becoming too much for him, he ran down into the valley to freshen himself up with cool spring water. While running he hit his foot against a rock and fell on all fours on the stone. Then he stood up, went to the spring, put his feet and hands in the spring and washed with spring water. That is where he got the great strength, he had taken that rock against which he had hit his foot, and played with it as if it were a potato. That rock is said to be still there on the edge of Väike-Maarja memorial hill, covered with moss. (6)

Near Pärnu people say that Lurich has so much strength because his two lower ribs had grown together and he is said to know a weak point in man's body, so that if you push it, the man will be feeble. (7)

When Georg Lurich had been a young boy, less than 10 years of age, his father had once bought seed peas and put them in the store in a bin. The boy had gone there to eat them. Father put a tchetvert [145 kg.] of rye in a sack on the lid of the bin. The boy had pushed down the sack of rye and still continued to eat peas. (8)

Once Lurich had walked in the forest and seen two men there, whose load of logs had fallen over. Lurich had lifted the load and pulled it onto the road. (9)

Peasants set the manor on fire. The master of the manor had insured the manor, the government paid the money. They themselves agitated the peasants on the manor. Then the landlords complained to the czar about the peasants. They all did so. The Estonians could not move. But then once Luuri went to talk to the czar. They would not let him, the guards are there. So then he pulled open his shirt. Medals all over his chest, they let him through.

He was a strong man. So then he talked how peasants were beaten, forced night and day. (10)

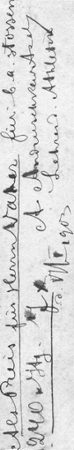

A postcard with the photo of Lurich. It was used by one of the leaders of Estonian heavy athletics, Adolf Andrushkevich on the diploma (1903). Estonian Sports Museum.

It is characteristic that in the stories of this subgroup Lurich gets on well with common people, he is always ready to help them and punish evil forces. He does not mind using his great strength; he is helpful and well-disposed towards people. As a rule the existence of strength is connected with some magic pattern. The comparative study of this matter (for example the origin of the special abilities of heroes and healers) would be fruitful.

Lurich as the traditional hero of a folk tale

In its extent this group is smaller than the ones mentioned before. As an answer to the question why this is so, one reason might be that the tales about Lurich mainly carried a specific function - to show the hero as a protector, helper, keeper (Lurich as a symbol) and therefore were exhausted quite soon due to the lack of variety. Certainly this hypothesis needs further revision. Anyway people have engaged the great strength of Lurich into their service. Examples:

Once one old woman's cow went over the fence. The old woman is in trouble. Luuri had seen that and asked if she could not get the cow over the fence. Went there, took the cow in his hands and lifted over the fence. (11)

Once he [Lurich] had unharnessed the horses from the plough and started to plough the field himself instead of the horses. (12)

At Pööravere tavern there is a large rock called Lurich's rock, because once Lurich had ousted that rock. Since that day the rock was called Lurich's rock. (13)

In old days a strong man lived in Pühajärve parish. He was so strong that when he rode a horse, and when the horse was tired, he carried it on his back. Once he had lifted the coachman's two horses up at a time. That strong man's name was Luuri. (14)

In the tales of this group Lurich is less lively than in those above. He is helpful, always ready to help the one in need and use his great strength. The name of Lurich becomes the symbol of a strong man, defender and helper of people.

In summary

In general we may say that Lurich as the hero of Estonian folk tales has become a hero mainly because of his great physical strength and because he is not ashamed of using his strength. Considering the whole material, his character is much richer in nuance: the humorous, short-tempered and demanding wrestler and coach (tales of the first group) becomes the prototype of a traditional man of muscle (tales of the second and especially the third group), through which Lurich became a symbol, the bearer of a specific function.

What is the proportion of historical truth and narrative truth in the tales about Lurich? Undoubtedly the tales of the first group were believed, they had a sound historical background. In the second group the narrator has created an illusion of reality: what is narrated in the stories might really have happened historically, the stories reflect the narrator's wishful thinking. The third group is completely based on narrative truth, which is expressed in the style of the narratives, also in the narrators' attitude to the hero. Lurich is seen as a character who in the opinion of the narrator performs (heroic) deeds.

According to Oskar Loorits, who has studied the prototypes of Estonian heroes, we may suppose that great strength in the peasant society was remarkable and worth telling stories about it (Loorits 1927: 37-71). Maybe Lurich knew how to make use of this rustic preference to create a legend of himself?

Translated by Ann Kuslap

References:

Archives of Estonian Folklore (Tartu):

- ERA - The folklore collection of Archives of Estonian Folklore in manuscripts (1927-1944).

RKM - The folklore collection of the folklore department of Estonian Acad. Sci. Fr. R.Kreutzwald Museum of Literature (1945-1996).

Estonian Sports Museum (Tartu):

- KV - private collection of Kalle Voolaid.

Hallismaa, Haljand 1998. Eesti raskejõustiku isa Gustav Boesberg. Tallinn: Olion.

Hiiemäe, Mall 1978. Kodavere pajatused. Tallinn: Eesti Raamat.

Jaago, Tiiu & Jaago, Kalev 1996. "See olevat olnud ..." Rahvaluulekeskne uurimus esivanemate lugudest. Tartu: Tartu Ülikooli Kirjastus.

Kristjanson, Georg 1973. Eesti raskejõustiku ajaloost. Tallinn: Eesti Raamat.

Langsepp, Olaf 1996. Georg Lurich. - 100 aastat Eesti raskejõustikku. Tallinn: Eesti Entsüklopeediakirjastus, lk. 26-41.

Loorits, Oskar 1927. Vägilaste prototüüpe. - Album M. J. Eiseni 70. sünnipäevaks. Tartu, lk. 37-71.

Pirsko, Priit 1995. Talud päriseks. Protsessi algus müüjate ja ostjate pilgu läbi. - Arukaevu, Jaanus & Jansen, Ea (toim.). Seltsid ja ühiskonna muutumine. Talupojaühiskonnast rahvusriigini. Tartu & Tallinn, lk. 97-117.

Propp, Vladimir 1976. Folklor i deistvitelnostj. Moscow.

Sepp, Reino 1984. Kui suur oli Lurich? Stockholm, Baltic Scientific Institute in Scandinavia.

Veedam, Voldemar 1981. Lurich Ameerikas. Toronto: Oma Press Ltd.

Vilder, Valdemar 1996. Eesti spordielu Austraalias. - Eesti Spordimuuseumi ja Eesti Spordiajaloo Seltsi toimetised I, lk. 106-110.

References from text:

(1) The material collected as a result of this campaign is at present in the folklore archives of the Estonian Literary Museum (RKM II 45, 609-649). Back

(2) RKM II 45, 609-649. Back

(3) RKM II 45, 609-649. Back

(4) RKM II 45, 609-649. Back

(5) RKM II 45, 609-649. Back

(6) RKM II 45, 609-649. Back

(7) RKM II 45, 609-649. Back

(8) ERA II 167, 325 (14) - Gustav Sommer < Hans Kallas (1937). Back

(9) RKM II 45, 609-649. Back

(10) KV: Nissi parish - Kalle Voolaid < Paul Sinisaar. Back

(11) ERA II 227, 191 (52) - Bernhard Parek < Miina Puust, 52 yrs. (1939). Back

(12) RKM II 45, 609-649. Back

(13) RKM II 45, 609-649. Back

(14) ERA II 242, 333 (6) - Aino Jõgi < Miina Mets, 57 yrs. (1939). Back